The “Atlanta campaign” is the name given by historians to the military operations that took place in north Georgia during the Civil War (1861-65) in the spring and summer of 1864.

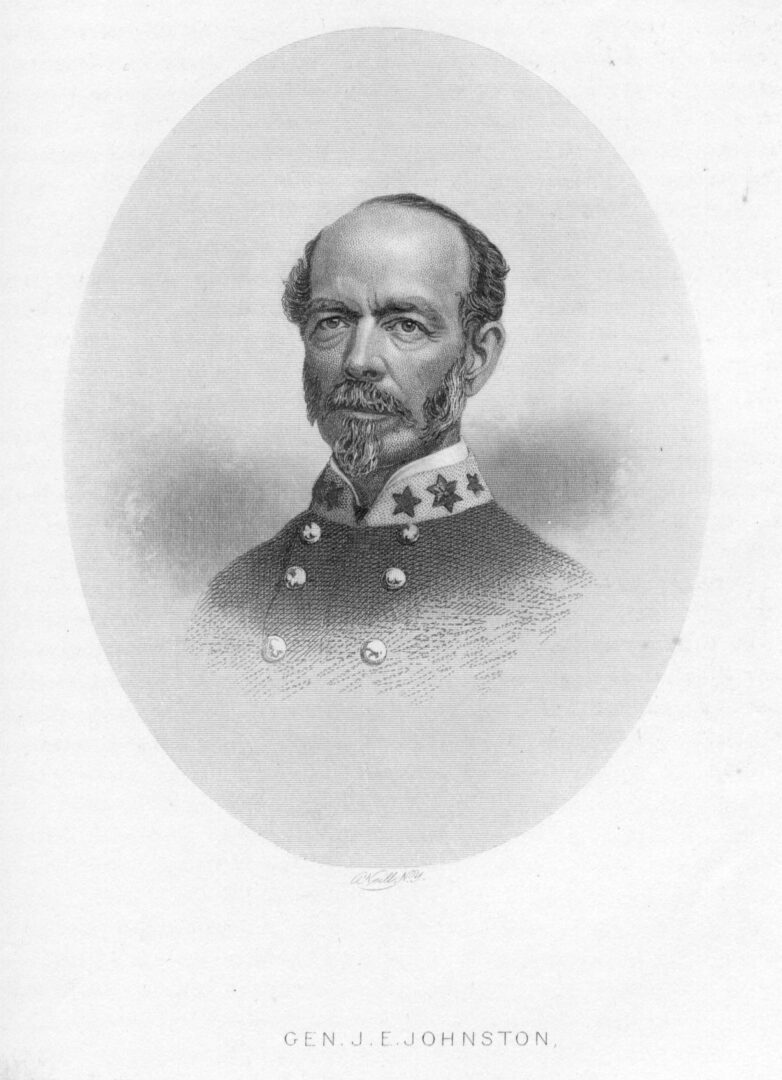

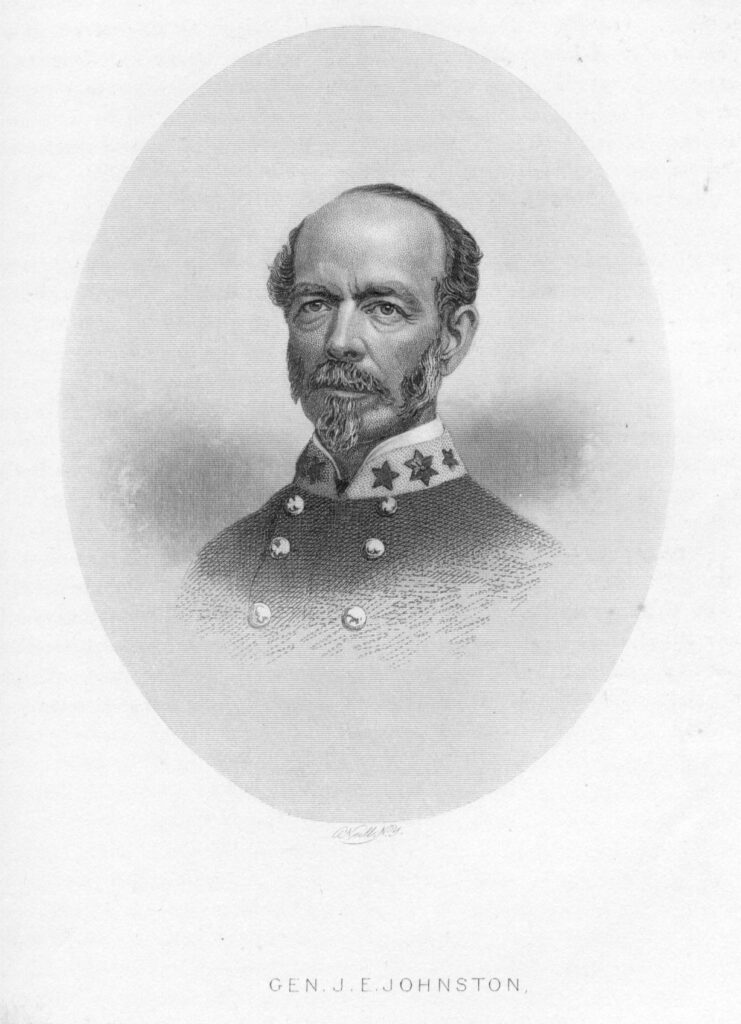

By early 1864 most Confederate Southerners had probably given up hopes of winning the war by conquering Union territory. The Confederacy had a real chance, though, of winning the war simply by not being beaten. In spring 1864 this strategy required two things: first, Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s army in Virginia had to defend its capital, Richmond, and keep Union general Ulysses S. Grant’s forces at bay; and second, the South’s other major army, led by Joseph E. Johnston in north Georgia, had to keep William T. Sherman’s Union forces from driving south and capturing Atlanta, the Confederacy’s second-most important city.

This win-by-not-losing strategy involved a time element as well. If Lee and Johnston could hold their respective fields through early November, then war-weary Northerners might vote U.S. president Abraham Lincoln out of office. The Democratic candidate, in turn, might seek an armistice with the Confederacy and end the war.

Synopsis of the Campaign

The stakes were high in early May 1864, when the Atlanta campaign began with the skirmish at Tunnel Hill in north Georgia. Sherman had four reasons to be confident of success: first, numerical advantage (his troops outnumbered Confederate forces by roughly two to one); second, an efficient supply system to keep his armies fed, clothed, and armed; third, superior morale (the Confederate army had just been routed from Chattanooga, Tennessee, the previous November); and fourth, and probably most important, Johnston’s record as an unaggressive, even timid army commander. Sherman, having faced—and beaten—Johnston in Mississippi the previous summer, was aware of this weakness in his adversary.

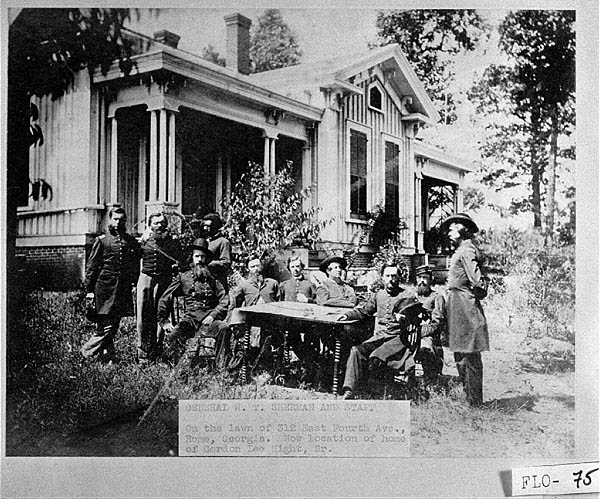

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

During the opening weeks of the campaign, Sherman seized the initiative and forced Johnston’s army back from one position to another. By late May some Atlantans had begun to think that the fall of their city was inevitable. After Johnston had been pushed back nearly to Atlanta in late July, Confederate president Jefferson Davis feared that Atlanta would be given up without a fight. So he fired Johnston and replaced him with John B. Hood, an army corps commander who promised to attack Sherman and attempt to save the city.

Hood’s chances of success, however, were virtually zero. Sherman’s forces were five miles from Atlanta’s outskirts when Hood took command of the Confederate army on July 18. Union strength stood at 80,000 to Hood’s 50,000. Outnumbered and lacking strategic options, Hood nevertheless sought tactical opportunities. He launched three assaults around Atlanta between July 20 and 28 but was repulsed each time. Sherman spent the next month bombarding the city and its remaining residents, while cutting the three railroad lines that supplied Hood’s armies. When the last of these lines, north of Jonesboro, was broken on August 31, Hood was forced to evacuate Atlanta. Sherman had won the campaign. Lincoln’s reelection was assured, and the Confederacy was doomed.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

The Union Advantage

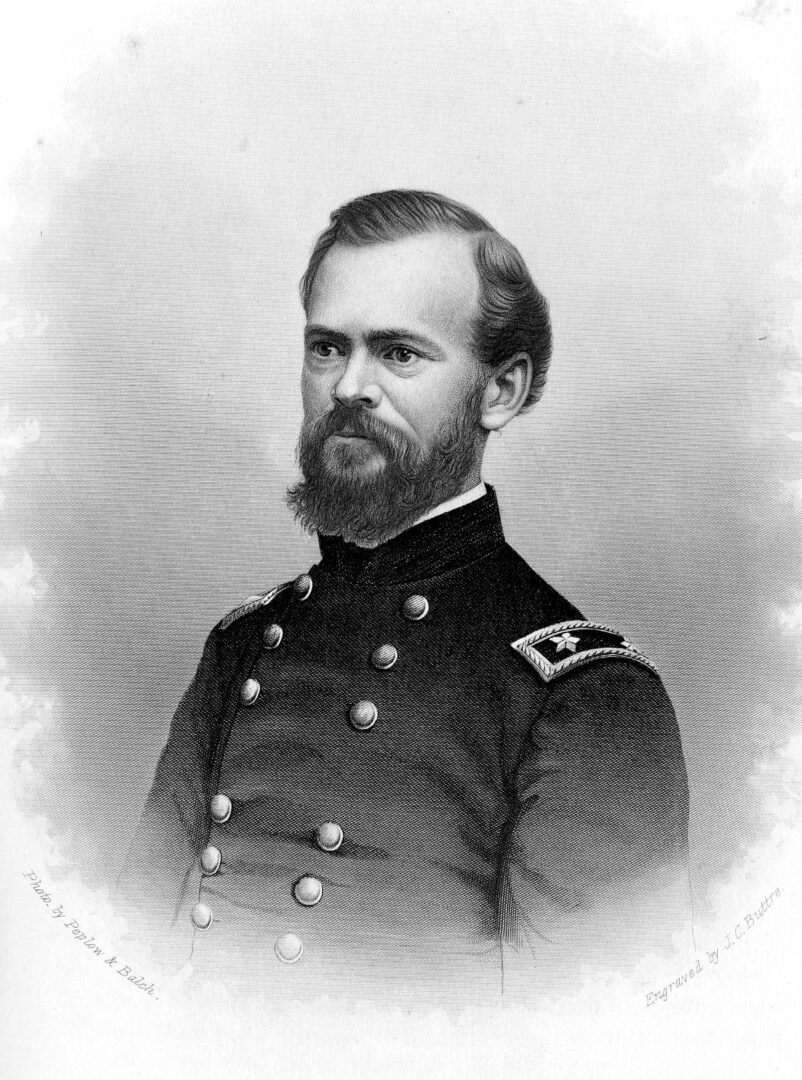

After his appointment in March as general-in-chief of the Union armies, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant placed Sherman, his trusted subordinate, in command of all three Union armies between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River: the Army of the Cumberland (Major General George H. Thomas), the Army of the Tennessee (Major General James B. McPherson), and the Army of the Ohio (Major General John M. Schofield). Sherman brought these armies together to form, by late April, a group of 110,000 men and some 250 cannons, all assembled around Chattanooga. Facing them near Dalton was the Confederate Army of Tennessee, which had been defeated and driven from Missionary Ridge the previous November and was now under a new commander, General Joseph E. Johnston. Numbering 54,500 officers and men on April 10, plus 154 artillery pieces, the army had been snapped back into shape during the winter by Johnston.

From The History of the State of Georgia, by I. W. Avery

In the instructions given to them by their superiors, neither Johnston nor Sherman was informed about the taking of Atlanta as a military objective. Grant simply ordered Sherman to move against Johnston’s army, “break it up,” and get as far into the enemy’s country as he could, wrecking their war resources along the way. As for the Confederate plans, President Davis wanted Johnston to advance back into Tennessee, but Johnston argued that, outnumbered and blocked at Chattanooga, he could assume no offensive. Davis reluctantly accepted Johnston’s logic. The Confederates therefore stood on the defensive, aware that Sherman’s thrust would be toward Atlanta, the occupation of which, as a pivotal industrial and railroad center, was key to the war’s outcome.

Sensible of his troops’ superior numbers and morale, and shrewdly anticipating his opponent’s passive disposition, Sherman was supremely confident of success. On April 10 he sent Grant his outlines for taking the city, once he had pushed Johnston back to it. First, he would maneuver around Atlanta and cut the railroads leading into the city, forcing the Confederate defenders to evacuate through want of supplies. Then he would push farther still into Georgia. In contrast to Sherman’s confidence, Johnston was fearful and pessimistic at the start of the campaign. He called for reinforcements just to hold his lines and at times seemed doubtful of his ability to manage even that.

Sherman Flanking, Johnston Retreating

Sherman began marching his troops on May 5, and his opening maneuvers set the stage for the rest of the campaign. With Johnston’s army formidably dug in along Rocky Face Ridge north of Dalton (and Johnston prepared to be attacked there), Sherman refused to launch a head-on assault against the Confederates. Instead he used Thomas’s and Schofield’s armies to demonstrate against Johnston’s main position, while McPherson’s column stealthily marched southward through undefended Snake Creek Gap, gained the enemy flank, and threatened, on May 9, the Western and Atlantic Railroad, the line running from Atlanta to Chattanooga that supplied the Confederate army. During the night of May 12-13, Johnston retreated to Resaca, a dozen miles south of Dalton, and dug into a new position. Sherman brought his forces up and repeated his previous maneuver, testing the Confederate lines with short, sharp attacks on May 14-15, while part of McPherson’s army flanked to the south and crossed the Oostanaula River. Johnston ordered another retreat to take place the next night.

From Photographic Views of Sherman's Campaign, by G. N. Barnard

The Southerners, clinging to the railroad, withdrew toward Cassville, just north of Cartersville. The Northerners followed in several widely separated columns. Johnston, seeing an opportunity to attack one of the Union columns, issued battle orders on the morning of May 19. He called it off, however, when enemy cavalry threatened his attacking column before the battle ever started. Johnston ordered another retreat, this time across the Etowah River to Allatoona. To his superiors in Richmond and to the Georgians increasingly alarmed at the Union advance, Johnston gave no assurances of any plan other than choosing successive defensive positions until he was flanked out of them. Moreover, even though the Confederate administration sent almost 20,000 reinforcements to his aid by late May, Johnston kept to his cautious, retrogressing strategy and allowed the enemy a leisurely, uncontested crossing of the Etowah on May 23.

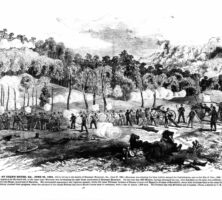

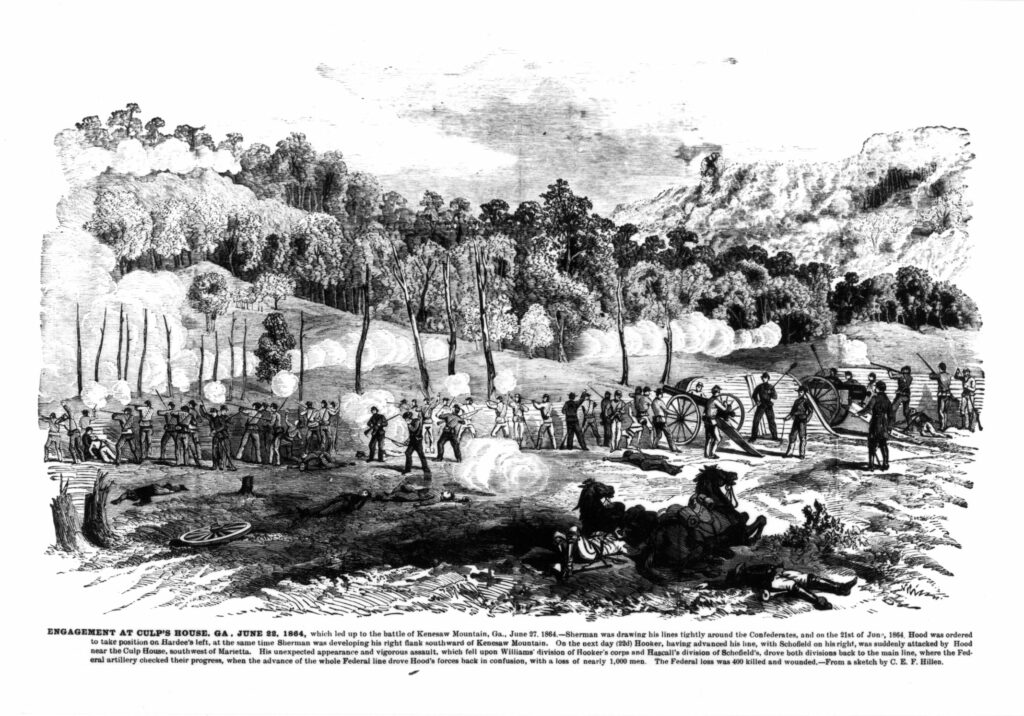

Sharp Fighting Near Dallas and Kennesaw

Sherman maintained his initiative. Knowing the strength of the Confederate position at Allatoona, he bypassed it altogether and struck to the southwest, away from the railroad and toward Dallas. Johnston sidled west to confront him in a new line, which Sherman tested in severe fighting at New Hope Church on May 25 and Pickett’s Mill on May 27. Standing on the defensive, the Confederates easily repulsed Sherman’s attacks. Casualties for the four days from May 25 to 28 at the “Hell Hole” (the Northerners’ name for the area), counting a costly Southern reconnaissance-in-force on May 28, were roughly 2,600 Union and 2,050 Confederate troops.

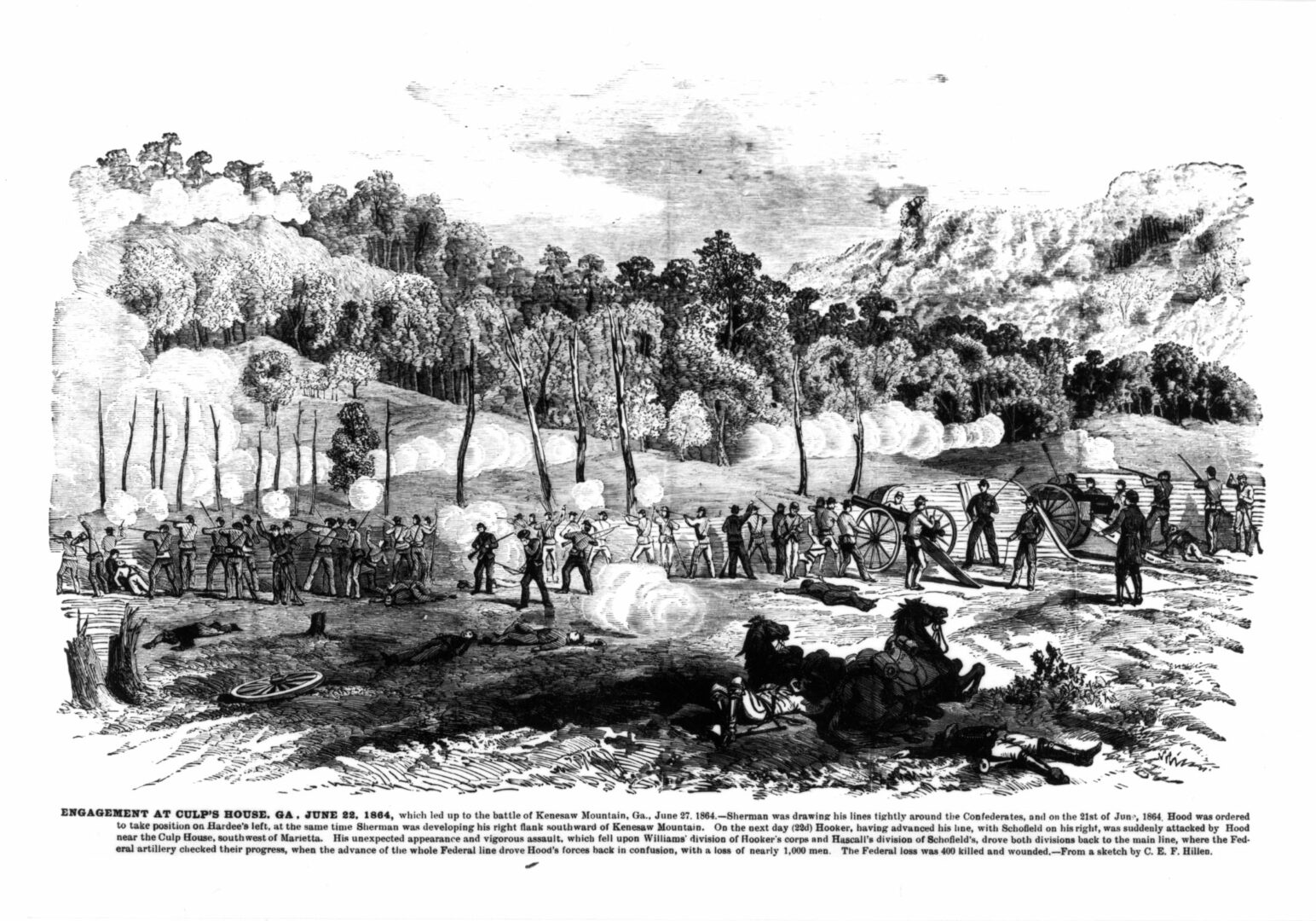

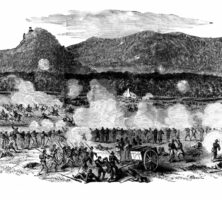

After his cavalry secured Allatoona Pass on June 3, Sherman moved his forces eastward, back to the railroad. Johnston stayed ahead of him, digging in around Kennesaw Mountain. Reinforced by a full infantry corps from Mississippi, the Union army still held a ten-to-six numerical edge in early June, an advantage of which Johnston was keenly aware and which fed his unaggressive posture. For several weeks Sherman was stymied in his maneuvers by almost daily rains, but he tried to force the issue with an attacking battle on June 27 against the Confederate lines at Kennesaw Mountain. Quickly repulsed, the Union army lost 2,000 troops, killed, wounded, and captured, to the Confederates’ 400. Skirmishing and cannonading along the rest of the lines (an almost daily occurrence by this point in the Atlanta campaign) brought Union and Confederate casualties on that day to an estimated 3,000 and 1,000 respectively.

Courtesy of U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

When the rains ended, Sherman returned to his flanking strategy on July 2-3 and forced Johnston to retreat about six miles from Kennesaw to a new line south of Marietta. Sherman’s forces again pressed forward, skirmished, cannonaded, probed, and marched so that in forty-eight hours the Confederate army again withdrew, this time to fortifications on the very north bank of the Chattahoochee River.

Hood Replaces Johnston

Sherman’s smart combination of numbers and flanking had brought his armies to the vicinity of Atlanta, and the city’s residents were justifiably alarmed. Some had already fled. Johnston’s orders in mid-May for the evacuation of Atlanta’s army hospitals and munitions machinery heightened the public distress. When Sherman’s probes up and down the Chattahoochee secured a crossing on July 8 at Roswell, the Southern army retreated across the river during the night of July 9-10 and took up a position south of Peachtree Creek.

From a sketch by C. E. F. Hillen

Mirroring the alarm in Atlanta, President Davis feared that the city would be abandoned without a fight. On July 10 he began to consult with his cabinet and to inform Robert E. Lee and Georgia senator Benjamin Hill of the need to replace Johnston, despite the fact that Sherman was looming at Atlanta’s gates. A week of deliberations, including Davis’s blunt telegraph to Johnston inquiring about his plans (answered quite evasively), led to the Confederate government’s replacement of Johnston on July 17 with one of the army’s corps commanders, General John B. Hood, who was well known for his pugnacity and willingness to attack.

A Confederate Commander

Hood accepted command and, with it, the unfavorable odds. His army, about 50,000 strong, faced around 80,000 Union troops, whose advance was five miles from the city’s outskirts. Working to Hood’s advantage were the impregnable fortifications around the city, which had been in construction by the Confederates for more than a year. At the same time, Thomas’s army was crossing Peachtree Creek; McPherson’s army, having swung wide to the southeast, had struck the Georgia Railroad (Atlanta to Augusta) east of Decatur and was marching and destroying track westward toward the city; and Schofield’s army was positioned northeast of Atlanta. Hood saw an opportunity to strike Thomas while the other two enemy armies were too far away to give support. Accordingly, he issued plans for an attack on the afternoon of July 20. In the resulting Battle of Peachtree Creek, the Confederates attacked, gaining minor tactical successes, but were ultimately repulsed. Casualties numbered 2,500 Southern and 1,700 Northern.

From Photographic Views of Sherman's Campaign, by G. N. Barnard

As McPherson pushed closer to the city from the east, his army presented the next target for Hood. In a bold maneuver reminiscent of Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s flanking assaults, Hood called for a third of his infantry to march south through the city, position on McPherson’s left flank-rear, and attack. The Battle of Atlanta, on July 22, resulted in the Confederates’ greatest success of the campaign, with approximately 3,600 casualties (including McPherson), 12 captured cannons, and a division-length of trenches rolled up. But here too the Confederates were ultimately repulsed and lost an estimated 5,500 men.

From The History of the State of Georgia, by I. W. Avery

True to his plan of cutting Atlanta’s railroads, and having already cut the lines heading east out of the city, Sherman swung the Army of Tennessee, now under Major General Oliver O. Howard, to the north of town and threatened the Confederate army’s remaining rail lines to the south. Hood again ordered a flanking attack, scheduled for July 29, against Howard’s army. The Confederate divisions marched out on July 28 to get into position, but the Union troops’ unexpectedly quick advance led the Confederate officer in charge, Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee, to order a premature frontal attack. The Battle of Ezra Church, on July 28, handed Hood a quick repulse and the loss of 4,600 killed, wounded, or captured troops, while Howard’s losses of 700 men were considerably lighter.

The Fall of Atlanta

The Confederates quickly constructed a fortified railway defense line to East Point (six miles southwest of downtown Atlanta) that blocked the further advance of Union troops. Sherman, however, was determined to pound Hood out of the city. On July 20 he ordered that any artillery positioned within range begin a cannonading, not just of the Confederate lines but also of the city itself, which still held about 3,000 civilians (down from 20,000 earlier in the spring). The artillery barrage reached its height on August 9, when Union guns fired approximately 5,000 shells into town. Civilian casualties during the five-week bombardment were remarkably low; the townspeople who decided to remain in the city found shelter in basements or “bombproof” dugouts. During Sherman’s barrage and semisiege of Atlanta (so called because at no point could the Union army completely invest the city’s eleven-mile perimeter of works), about twenty civilians were killed. The number of wounded and maimed must be judged much higher, although Southern medical records offer no precise data.

Though his own headquarters came under shellfire, Hood refused to budge. Supplies continued to arrive into the city from Macon, even after the third railroad (to Montgomery) had been cut in mid-July by a Union cavalry raid in Alabama. Sherman tried twice to cut the last railroad, the Macon and Western, with cavalry raids in late July and mid-August. After these attempts failed (with a few miles of torn track quickly repaired), Sherman concluded that only a massive infantry sweep would cut the Macon Road. On August 25, with his forces withdrawn to guard the Chattahoochee bridgehead northwest of Atlanta and his siege lines abandoned, Sherman marched most of his army (six of seven corps) south and then southeast toward Jonesboro, fifteen miles from Atlanta.

From Photographic Views of Sherman's Campaign, by G. N. Barnard

Hood found that he could not stretch his outnumbered army far enough. With a third of his infantry and state militia forced to man the city defenses, he tried to send his troops down the railroad to meet the new threat. When Howard’s army approached cannon range of Jonesboro and the railroad, Hood had no choice but to order an attack, which the entrenched Union troops handily repulsed on August 31. To the north on that same day, other Union troops actually reached the railroad and began wrecking the rails. Hood’s attempt to send the army’s reserve ordnance train southward failed as the engine, faced by enemy interdiction, had to chug back into the city. Hood was left with no option but to order the evacuation of Atlanta on September 1. Continued fighting at Jonesboro that day proved inconsequential—the fate of Atlanta was sealed when Sherman’s troops cut the Macon and Western line. Union soldiers entered the city on September 2, thus concluding the Atlanta campaign.

Photograph by George N. Barnard

Telegraphing Washington, D.C., General Sherman observed, “Atlanta is ours and fairly won.” Battle casualties for the four-month campaign totaled 37,000 Union and about 32,000 Confederate soldiers killed, wounded, and missing. In both armies roughly seven out of ten soldiers fell sick at some time; their incapacitation for duty probably affected both sides in equal proportion.

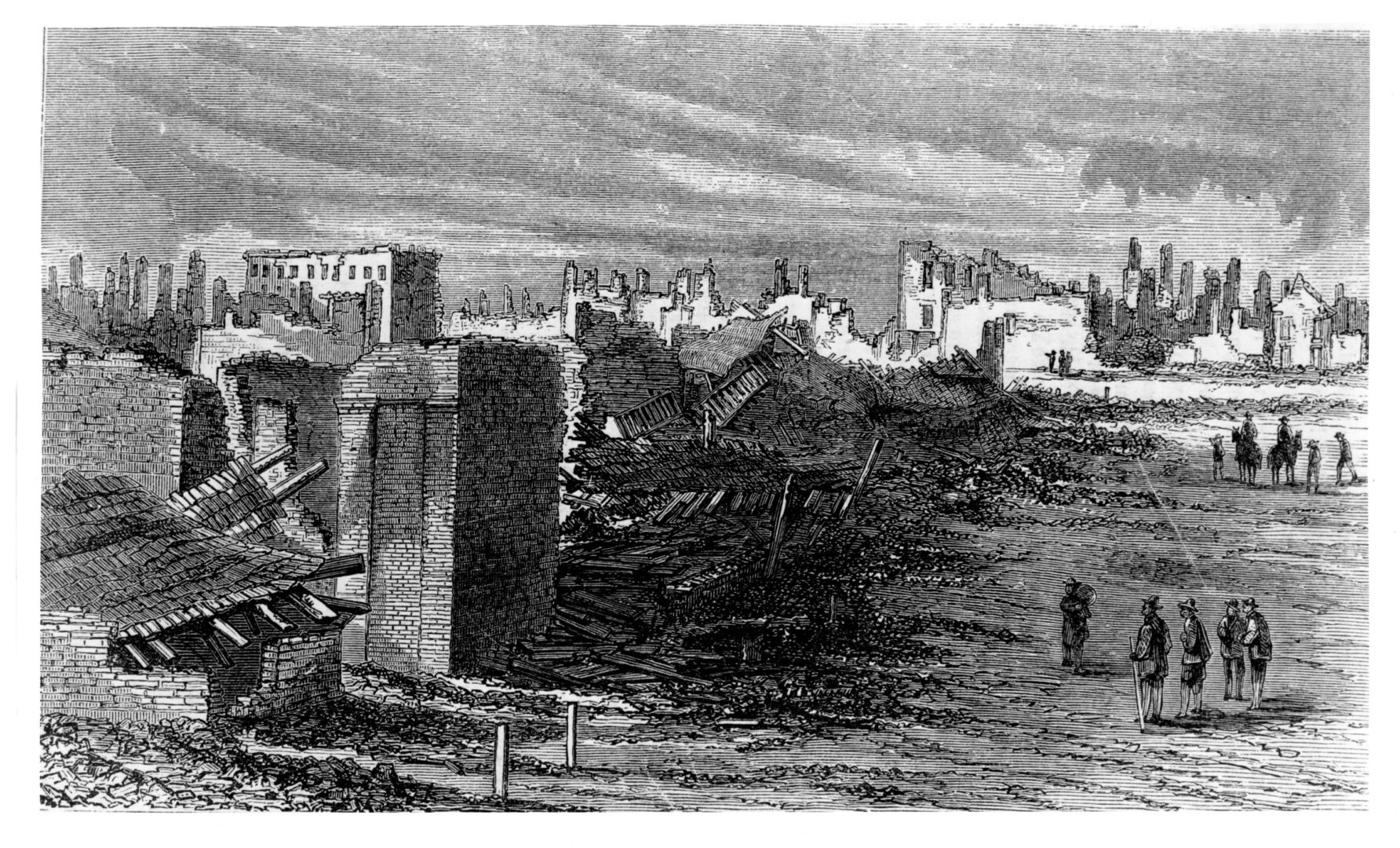

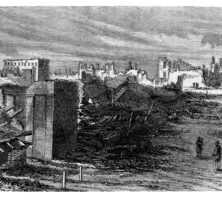

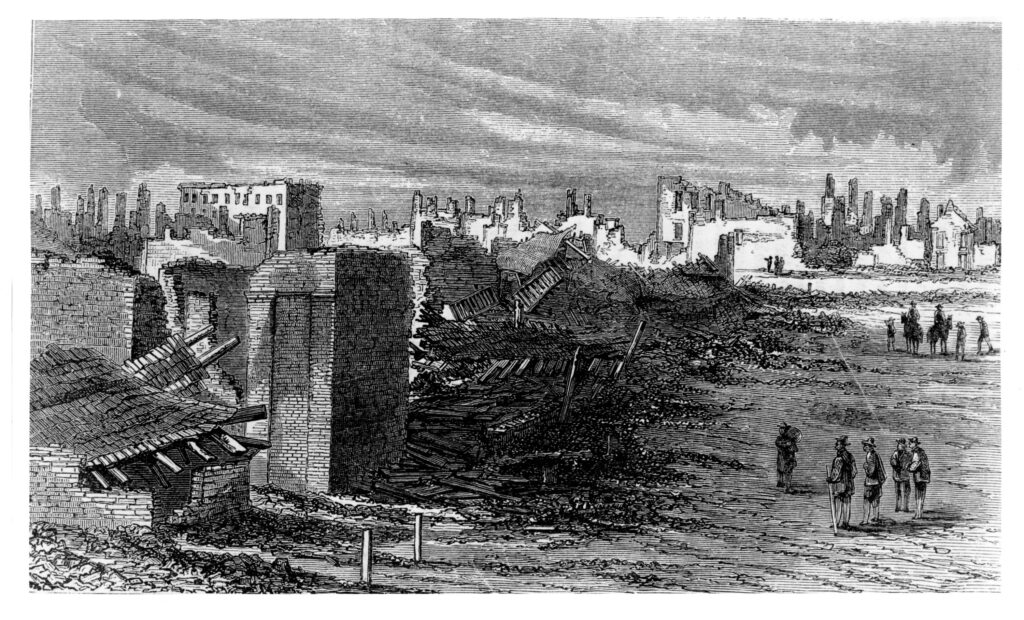

Sherman’s troops held Atlanta for two and a half months. Northern generals moved into the finer houses (Sherman occupied the John Neal home), while soldiers pitched camp in vacant lots or parks, such as those around City Hall, sometimes stripping buildings of wood to build shanties. In early November, with his plan set for a march to the sea, Sherman ordered his engineers to begin “the destruction in Atlanta of all depots, car-houses, shops, factories, foundries,” and the like. Some structures had already been destroyed; in addition, retreating Confederates had detonated an ammunition train, which had leveled the big rolling mill. Sherman directed that the structures be knocked down by his engineers first “and that fire only be used toward the last moment.”

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The work began November 12, after Union troops had sent north their last train loaded with materials that the army would not use in its upcoming march. Captain Orlando Poe, Sherman’s chief engineer, instructed his men to rip apart Atlanta’s railroads, heating and bending each rail over the burning wooden ties. Not until November 15 did engineers begin torching designated sites, some with explosive shells placed inside. A hand-drawn map (now at the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts) indicates the buildings that were destroyed, including a storehouse at Whitehall and Forsyth streets, a bank at the railroad and Peachtree Street, the Trout and Washington hotels, and various other structures.

Four days earlier, on the night of November 11, Union soldiers milling about town began to torch private buildings, especially residences. The young Carrie Berry, still living with her family in the city, recorded the event. (Her diary survived and is held at the Atlanta History Center.) Union officer David Conyngham related that about twenty houses were destroyed that night, ruefully and rather lamely attributed by Captain Poe later to “lawless persons, who, by sneaking around in blind alleys, succeeded in firing many houses which it was not intended to touch.” Fires were set each night from November 11 to 15, although army officials tried to prevent them by guarding certain properties and catching or punishing the perpetrators. Churches were particularly kept under guard, resulting in five of them being spared from the flames that eventually consumed much of downtown.

From Harper's New Monthly Magazine, v.31 (June-Nov 1865)

On the final night of the Union occupation, November 15-16, Union troops, encouraged by the arson carried out by the engineers, committed unlicensed burnings that set much of downtown afire. Viewing from headquarters the fiery glow over much of the city that night, Major Henry Hitchcock of Sherman’s staff predicted, “Gen. S. will hereafter be charged with indiscriminate burning.” The Union army left Atlanta the next morning.

News of Sherman’s capture of Atlanta provoked electric and tumultuous reactions in both the North and the South. The first significant Northern victory in 1864, the fall of Atlanta assured President Lincoln’s reelection in November, as well as a pledged U.S. prosecution of the war to victory. With the loss of Atlanta, Confederate defeat was only a matter of time.