The Augusta Canal, constructed in 1845, provides water to the city, power to factories, and transportation for canal craft. The canal rescued Augusta from a business depression in the 1840s and provided energy for war-related industries during the Civil War (1861-65). In the 1880s, it fueled an economic boom and then experienced neglect during the mid-1900s. The canal later benefited from a groundswell of popular support in the 1990s.

Image from TranceMist

Origins

The city of Augusta, situated at the Savannah River’s head of navigation, had served as an entrepôt between land and river traffic since its founding in 1736. However, due to a national depression and the western migration of many of its citizens, Augusta needed a resource other than commerce. Henry Cumming, son of the city’s first mayor, Thomas Cumming, took the initiative in a bold enterprise—the construction of a seven-mile canal from above the Savannah River rapids into the heart of Augusta. In November 1844, at his own expense, Cumming engaged John Edgar Thomson, chief engineer of the unfinished Georgia Railroad, to survey the route of the waterway and draw up plans. Thomson’s prestige provided credibility for the project.

Cumming credited William D’Antignac with proposing a creative scheme for financing the canal. Four banks agreed to put up $1,000 each as seed money. The city of Augusta issued bonds worth $100,000 to be redeemed by a “canal tax” levied on the value of property. Citizens received stock, or “canal scrip,” in proportion to the taxes they paid and voted for a board of managers. The city continued to contribute to the cost and became the largest stockholder. The city council named a special Canal Board of Commissioners to build the canal, and Cumming served as president of the canal board. The canal’s only paid employee, William Phillips, spent twenty-three years as secretary to the board and as chief engineer.

Construction

In May 1845 work began on twelve sections simultaneously. The original workers were white laborers from those parts of Georgia served by the Georgia Railroad; however, the summer’s heat decimated the white work crew, and Black labor—enslaved and free—finished the job. After digging began, the canal board made a controversial move and changed the outlet from east of Augusta to a point west of Augusta. Citizens in the lower ward objected and filed a suit against the city, contending that it had exceeded its authority in levying a canal tax and in extending the city limits over the seven-mile tract of the canal. Friends of the canal thwarted opposition by enacting state legislation that authorized the city to do what it had already done.

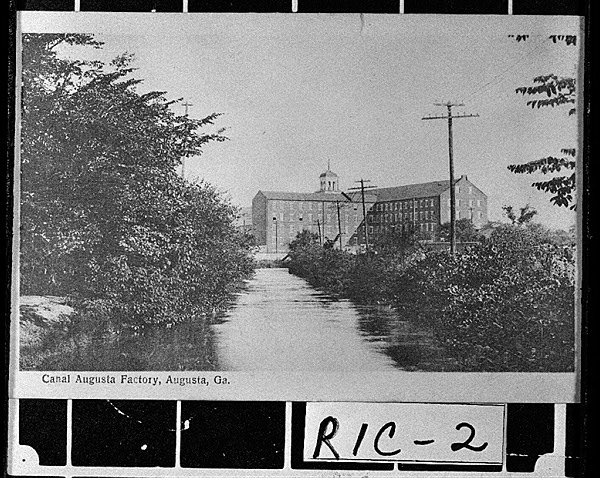

The lawsuit did not slow construction. By September 1845, 200 men were working on the first level. On November 23, 1846, the headgates opened for the first time and flooded the first level. In January 1847 the canal board hired Jabez Smith of Petersburg, Virginia, to supervise construction of the huge Augusta Factory at the terminus of the first level. James Coleman’s saw and gristmill began operations on the canal in April 1848, becoming the first industry to do so. In May the Augusta Factory began the production of textiles.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

During the next two years the canal board extended the second level five city blocks and built a third level that carried the water back to the river. Smaller shops opened for business on the second and third levels. The wooden aqueduct over Rae’s Creek on the first level proved troublesome, so the canal board replaced it with a stone structure in 1853. His work done, Cumming resigned with the gratitude of the city, as Augusta began its industrial expansion. William Phillips became chief engineer, and his major contribution was a modern waterworks system, completed in 1861, that replaced conduits of hollowed-out logs.

Industrial Growth

Because of the canal and because of Augusta’s rail connections, Colonel George W. Rains selected Augusta as the site of a massive Confederate Powder Works that supplied the Confederate army throughout the Civil War. Other war-related industries also sprang up along the three levels of the waterway. Augustans considered their city “the heart of the Confederacy.”

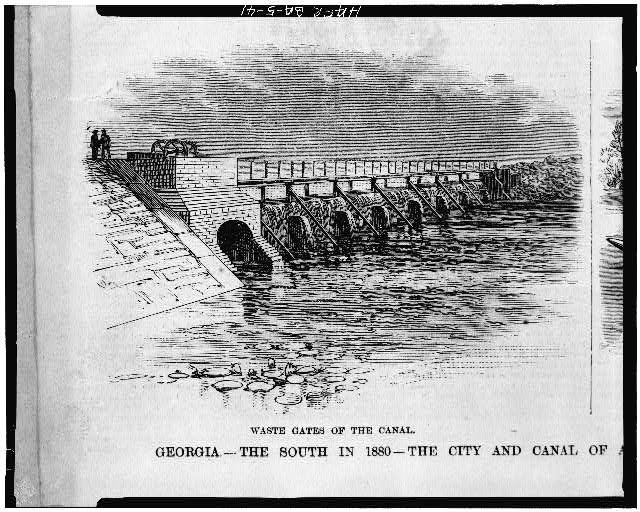

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

After the war, Colonel Rains suggested that widening the canal would allow for larger factories to be constructed. Mayor Charles Estes, himself a former contractor who had worked on the Erie Canal in New York, hired another Erie engineer, Charles Olmstead, to supervise the project. Work began in 1872. The canal was widened and deepened, even as Petersburg boats continued to ply its waters. Italian masons blocked up the stone aqueduct, damming Rae’s Creek and creating a lake named Lake Olmstead. The city hired more than 200 Chinese immigrants for the labor, many of whom remained in Augusta to form one of the oldest Chinese communities in the eastern United States.

Huge new factories, chief of which were the Enterprise (1877), Sibley (1880), and John P. King Mill (1882), rose along the canal banks. “Mill villages” clustered around the mills as families flocked from the depressed countryside to take jobs in the factories. Efforts to unionize the workers resulted in strikes in 1886 and 1898, but the mill managers broke both strikes by evicting strikers from company housing.

During the 1890s entrepreneur Daniel B. Dyer used waterpower from the canal to generate electricity for streetcars and streetlights, as well as for businesses and residences. In 1898 city engineer Nisbet Wingfield constructed both a new pumping station nearer to the headgates and a reservoir on the hill west of Augusta to serve the growing city. The availability of water led the U.S. Army to establish Camp Hancock near the reservoir during World War I (1917-18).

Two tragic incidents left memorials along the canal. In 1902 a young city worker, Dennis Cahill, drowned while attempting to rescue a young girl who had fallen into the canal. Citizens erected a monument to commemorate his heroism. Augusta native Archibald Butt, after assisting women and children into lifeboats, went down with the Titanic in 1912. Former U.S. president William Howard Taft presided over the dedication of a new bridge over the canal in honor of Butt, who had served as his aide. During the 1990s Augustans successfully demonstrated against efforts to demolish the Butt Memorial Bridge.

Decline and Restoration

Motor carriers eventually made canal transportation less important, and the availability of cheap electricity generated by power plants on the Savannah River rendered factories less dependent on waterpower from the canal. However, canal water continued to supply generators at the Augusta mills. From the 1920s to the 1960s, the city council attempted to find a way to build its own power plant on the canal and drain the major portion of the waterway. The city neglected maintenance, and the canal came to be regarded as a “cesspool.” During the first urban renewal project in 1960, the Augusta Factory was demolished, and the second and third levels dried up.

In 1971 Joseph B. Cumming, the great-grandson of Henry Cumming and head of the Georgia Historical Commission, surprised city authorities by placing the canal on the National Register of Historic Places, which in turn triggered interest on the part of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. By 1974 the state of Georgia and the city of Augusta had agreed on plans to build a park along the canal. However, a lack of funding delayed the project, and the city returned to the old temptation of converting the canal into a power plant.

Although the National Register nomination and the plans for a state park generated a grassroots movement for the preservation of the canal, the city nevertheless approved a contract for a power plant in 1991. At the same time, city leaders negotiated with a developer to build a golf course on virgin land between the canal and the river. Augusta’s citizens organized the Savannah Waterways Forum to oppose these ventures. “Save the Augusta Canal” bumper stickers appeared on automobiles all over the city. A privately funded replica of a Petersburg boat, successfully launched in 1993, increased interest in the recreational possibilities of the canal.

The groundswell of opposition forced the city council to reconsider its plans for the power plant. Ironically and coincidentally, the Federal Regulatory Commission informed the city that its license to build a power plant had expired. The city dutifully replied that it no longer wanted to construct a plant. The federal commission notified the city that if it did not apply, then any private company might do so. After a Duluth company filed an application, the city had no choice but to apply for a power plant that it no longer wanted. The federal agency then demanded an environmental impact study costing more than $800,000. The canal seemed caught in a bureaucratic nightmare.

Meanwhile, the Augusta Canal Authority, chartered by the state in 1989, completed a master plan elaborating on the canal-park concept and featuring the rewatering of the second and third levels. Public enthusiasm for the project persuaded U.S. senator Paul Coverdell to attach a rider to a land-management bill that designated the canal as a National Heritage Area. U.S. president Bill Clinton signed the bill into law on November 12, 1996, making the canal the first, and to date only, site in Georgia with this designation. The legislation permitted the canal authority to apply for up to a million dollars a year toward improvements until the year 2012.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia.

With this new access to funding, the canal authority published a history of the canal that provided the basis for an interpretive center at the renovated Enterprise Mill. The center offers a ten-minute orientation film, as well as exhibits detailing the historical and technical aspects of the canal’s construction and maintenance. The canal authority today uses canal water to generate electricity for its own use and sells the surplus to the Georgia Power Company. In 2004 the canal authority launched the second of its two custom-built Petersburg boats, appropriately named the Henry H. Cumming and the William Phillips. In cooperation with Columbia County, buildings at the headgates had been restored by 2005. A trail named after the naturalist William Bartram parallels the canal.

The recreational use of the canal today complements its traditional functions of providing water power to industry and drinking water to the public.