The manufacturing might of the North during the Civil War (1861-65) often overshadowed that of the South, but the success of the Confederate war effort depended as much on the iron of its industry as the blood of its fighting men. Over the course of the war, Georgia, known as the antebellum “Empire State of the South,” became an indispensable site for wartime manufacturing, combining a prewar industrial base with extensive transportation linkages and a geographic location secure for most of the war from the ravages of enemy armies. Manufacturing gunpowder, munitions, textiles, and a vast array of other essential materiel, Georgia’s industry kept the Confederacy fighting, if never quite as well supplied as its Northern opponent.

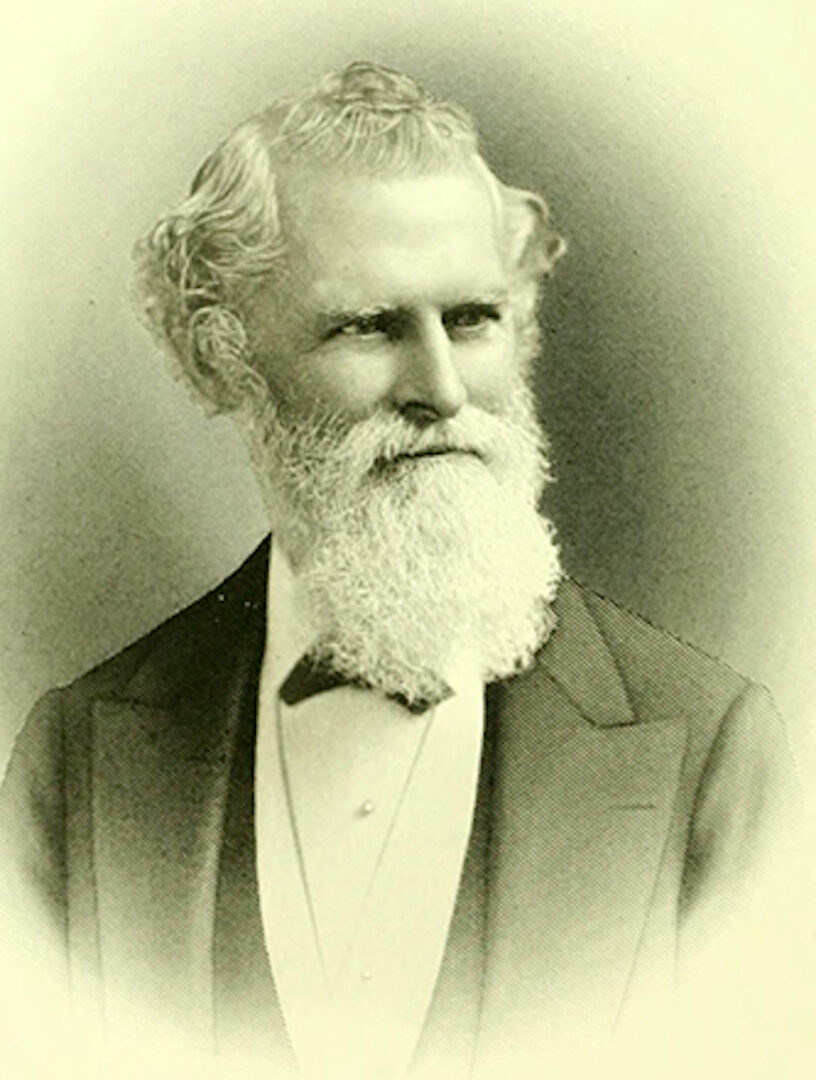

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Antebellum Industry

In the generation preceding the war, enterprising Georgians experimented with a variety of industries in an effort to lessen the state’s dependence on cotton cultivation. Cotton farming dominated Georgia’s antebellum economy, but by the mid-1830s declining prices fueled by overproduction led some to seek alternatives to agriculture’s boom-and-bust cycles. Industrial development offered one such alternative, and a flurry of investment enabled a number of nascent industries to appear throughout the state. Primarily located in fall-line cities like Augusta, Columbus, and Macon, these early manufactories provided the foundation for later efforts to supply Confederate armies.

Two of Georgia’s most important antebellum industries were textiles and railroads. Textile production was a logical extension of cotton farming, and Georgia was able to maintain a sizable industry, although it never effectively rivaled Northern output. Thirty-three mills were in operation on the eve of the war, producing the highest volume of textiles of any Southern state. At their peak during the war, these mills turned out more than 500,000 yards of cloth per week.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

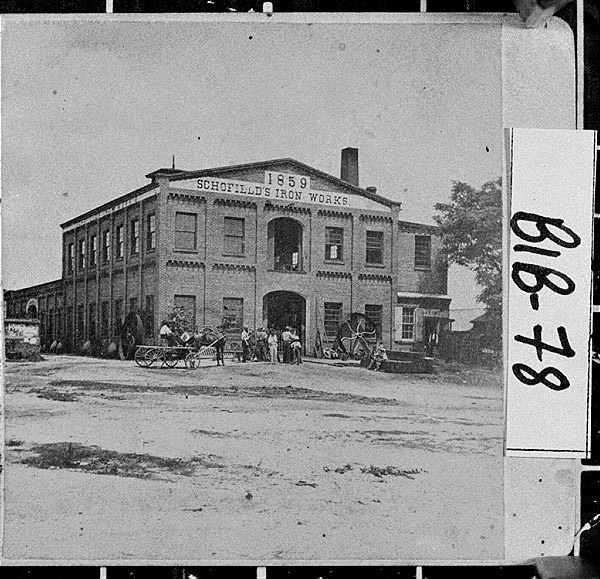

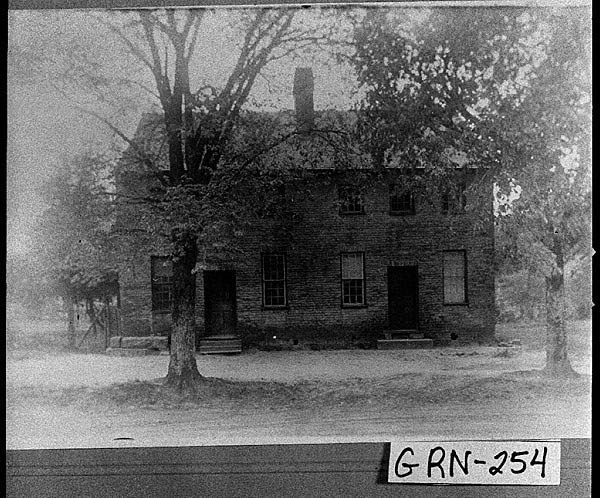

Railroad fever also swept Georgia in the 1830s, and though track mileage was slow to develop, by 1860 the state controlled 1,420 of the South’s 9,182 miles of track, second only to Virginia. Railroads spurred a host of associated industries, including iron foundries, rolling mills, and machine shops, all of which shaped and prepared iron, steel, and other metals for the many demands of the railroad business. These manufactories also branched out to produce other metal goods; Macon’s Findlay Iron Works, for example, built stationary steam engines for powering mills, cotton gins, and printing presses in the antebellum period. Railroads also effectively connected Georgia to the other states of the Confederacy, and by the beginning of the war, Georgia, and especially Atlanta, was the crucial nexus of Southern transportation and a heartland of Southern industry.

Powder and Munitions

In the spring of 1861 men throughout the Confederacy were ready to fight; Southern industry, though, was not ready to supply them. Gunpowder was especially scarce, and the Confederate states held stockpiles barely adequate to outfit their recently raised armies. With no domestic suppliers available, foreign sources offered, at best, only a temporary solution to the Southern states’ dilemma. If the Confederacy was going to fight a protracted war, it would be necessary to manufacture powder domestically and in bulk.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

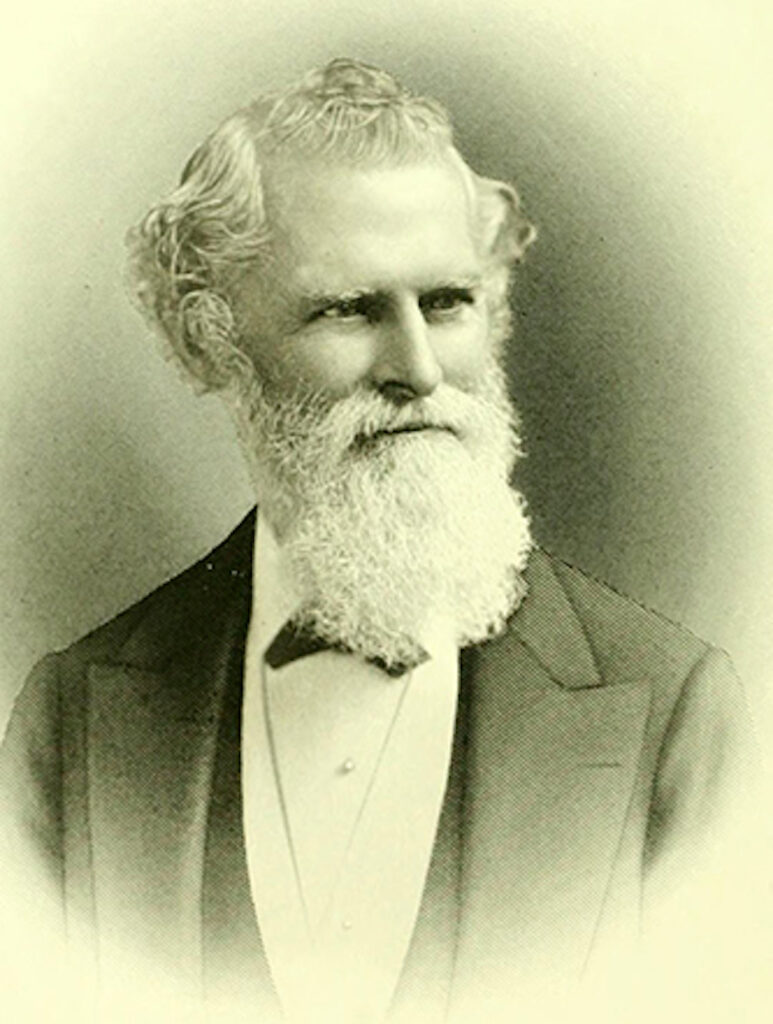

Leading this effort was Colonel George W. Rains, who at the behest of the Confederate Ordnance Bureau selected Augusta in July 1861 as the site of a massive powder works sufficient to meet the needs of the Confederate forces. Georgia’s prime geographic location made the state an ideal center for wartime munitions production; it was distant from the fighting fronts, and its extensive rail network allowed powder to be quickly moved wherever it was needed. Erected in a mere eight months, the works comprised a two-mile-long series of castellated Gothic revival buildings, straddling the Augusta Canal, that were designed to efficiently convert sulfur, niter (saltpeter), and charcoal into finished powder. At peak production, the Confederate Powder Works was capable of producing as much as 6,000 pounds of gunpowder per day, and by the end of the war, more than 3 million pounds had been produced.

Image from Lewis Historical Pub. Co., New York

Powder, though, does not constitute an effective weapon until it, along with a projectile, can be formed into a cartridge, loaded into a firearm, and detonated with a percussion cap, or otherwise ingeniously exploded. Arms and armament production, therefore, were also necessary for the Confederate war effort, and in Georgia these tasks were undertaken by a mix of public and private industry spread among the state’s larger urban centers. In Atlanta, Augusta, Columbus, Macon, and Savannah the Confederate Ordnance Bureau maintained arsenals that manufactured such munitions as bullets, caps, cartridges, and friction primers, along with other military supplies like knapsacks and saddles. Many of these arsenals would occupy the iron foundries, rolling mills, and machine shops of the antebellum years, while many private firms also converted to wartime arms production.

Given its railroad ties throughout the Southern states, Atlanta was home to the largest of Georgia’s arsenals, and the city also housed Confederate ironworks, which produced cannons, rails, and armor plate. Beginning operations in March 1862, the Atlanta Arsenal employed nearly 5,500 workers and acted as the primary ordnance supplier for the Army of Tennessee until its operations were removed farther south in July 1864. During its years of operation, the arsenal produced more than 46 million percussion caps, 9 million rounds of ammunition, and large quantities of other materiel. Further, companies like the Atlanta Machine Works manufactured forges for rifling muskets, and the Georgia Railroad’s machine shops added several small cannons.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Other cities, too, served as critical sites for Confederate munitions manufacture. The Columbus Arsenal produced more than 10,000 rounds of small-arms ammunition daily, while the Columbus Naval Iron Works manufactured and assembled cannons and boilers for Confederate gunboats. The Savannah Arsenal was forced to relocate to Macon, owing to the capture of Fort Pulaski in April 1862, but once there fabricated a variety of supplies, including the famous Parrott rifled cannon. Finally, a number of smaller towns contributed weaponry, including swords from Dalton; cannons and batteries from Rome; revolvers from Griswoldville, whose factory produced more pistols than any other firm in the Confederacy; and bayonets and rifles from Athens. (A two-barreled cannon was also produced in Athens but failed in testing and was never used in combat.)

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Quartermasters and Profiteers

Armaments were essential to waging effective war, but the Confederacy’s soldiers also needed to be clothed and shod. Georgia’s textile mills took up the task of producing cloth for uniforms, blankets, tents, and other uses, while the state’s 125 boot and shoe manufacturers turned out their wares as quickly as possible to keep the Confederate armies marching. Furthermore, in 1861 the Quartermaster Department constructed depots in both Atlanta and Columbus, representing the Confederacy’s second- and third-largest depots (after the one in Richmond, Virginia). These facilities assembled jackets, shirts, shoes, and trousers on a massive scale. For instance, in 1863 the Atlanta depot contracted to produce 175,000 shirts, 130,000 jackets, and 130,000 pairs of shoes for the Confederate forces. However, production never quite kept up with the army’s insatiable demand.

Textile and shoe manufacture showcased the persistent problem of scarcity plaguing Georgia’s wartime manufacturers. As winter approached in 1861, wool was in high demand and low supply throughout the South, and the state’s wool manufacturers were limited in their production by the unavailability of fibrous sheep fur. By 1863 the Confederate government had virtually monopolized the wool supply, forcing factories to produce only for government orders and leaving the civilian population with little access to woolen goods. Representing a broader trend, the Quartermaster Department’s persistent purchases (or impressments) of the bulk of the state’s textile and shoe manufactures left civilians facing intense scarcity and exorbitant prices. These conditions often led to accusations of profiteering, pressuring the Georgia legislature to pass a Monopoly and Extortion Bill as early as December 1861.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Industry was also hampered by a lack of consistent labor; the manpower requirements of the perpetually outnumbered Confederate armies worked against wartime manufacturers by drawing skilled labor to the front. In the place of these white male workers, both white women and enslaved African Americans filled in to keep Georgia industry productive. At the start of the war, women in the textile industry were already doing a larger share of the unskilled, low-wage work than their male counterparts, with 1,682 women to only 1,131 men working in textile production in 1860. As the conflict progressed, more than 4,500 seamstresses would work in government depots in Augusta and Atlanta, while women were also instrumental in assembling small-arms munitions for the Augusta Armory. Bondsmen, too, were used extensively in Georgia manufacturing, working in heavy industry primarily as common laborers. By 1863 around half the workforce at both the Macon Armory and the Augusta Powder Works were African American, and Blacks also built and maintained the state’s rail network by constructing bridges, grading, and laying new track. The state was so desperate for labor that, late in the war, convicts in the Milledgeville penitentiary were employed making shoes.

An End and a Beginning

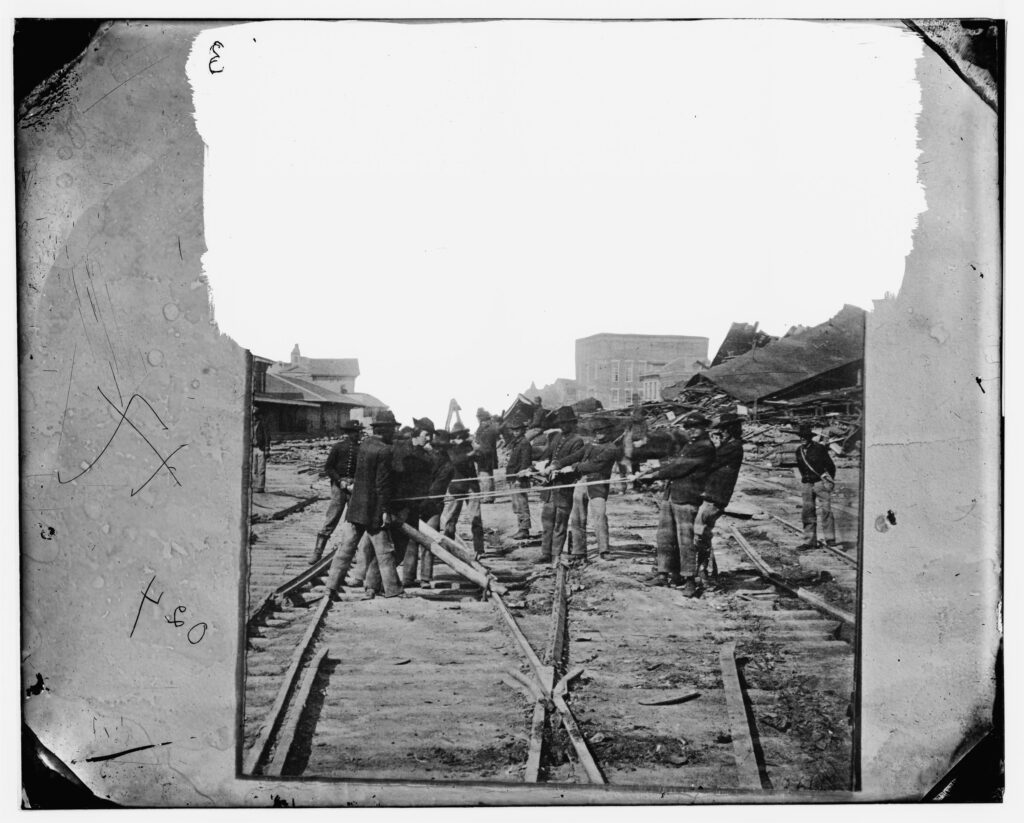

Still, the lack of resources and manpower was far from the most destructive force facing Georgia industry; that honor goes to the army commanded by Union general William T. Sherman. Sherman’s Atlanta campaign and later march to the sea brought total war to Georgia and with it the destruction of much of the state’s industrial capacity. The railroads that connected Georgia’s industry to the rest of the Confederacy were a primary target for Sherman’s forces, who followed the tracks from Tennessee to Savannah, ripping up rail as they went. Atlanta’s factories were totally destroyed, and much of the city was burned. Cities like Augusta and Macon were spared, but without the rail connections through Atlanta, the products of their factories faced increasing difficulty in reaching the remaining Confederate forces.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The collapse of the Confederacy, though, did not presage the decline of Georgia’s industry; in fact, the roots of Georgia’s New South efforts can be distinctly traced to the state’s manufacturing experiences during the Civil War. The stimulus of war expanded industry across the state, such that between 1860 and 1870 the number of establishments increased from 1,890 to 3,836, and the value of yearly product nearly doubled, from $16.9 million to $31.1 million. Atlanta, once rebuilt, surged into the postbellum period intent on forging a new identity, one less reliant on Northern manufactures and more capable of producing needed goods at home. Industry continued to blossom across the state, and though cotton production still dominated, a more balanced economy emerged in the wake of Southern defeat. Yet, while the war lasted, Georgia remained a critical supplier of materiel and men, iron and blood, to the cause of Southern independence.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.