During the summer of 1946, Atlantans witnessed the rise of the Columbians, the nation’s first neo-Nazi political organization. The group pursued a campaign of intimidation against the city’s minorities, patrolling those neighborhoods most vulnerable to racial transition, and threatening with violence those residents who dared cross the city’s “color line.” Although they attracted some support from Atlanta’s working-class whites, the Columbians were uniformly condemned by the city’s press and targeted for arrest by its political establishment. By the following summer the group had dissolved, following the conviction of its leaders, Homer Loomis and Emory Burke, on charges of usurping police power and inciting to riot.

Background

Homer Loomis arrived in Atlanta in 1946 amid escalating racial tensions. Across the South, incidents of racial violence and civil unrest were on the rise; lynching had become more frequent, and such hate organizations as the Ku Klux Klan had increased in both number and activity. Such an environment appealed to Loomis, a thirty-two-year-old New Yorker. Although his personal history read like a litany of failure—expulsion from Princeton University in New Jersey for drunkenness, two failed marriages, and an unsuccessful stint farming—Loomis fancied himself a leader among men, and he came to the South in order to start a white supremacist movement. “Atlanta is the logical place to start something,” he explained. “The South comes by its racial convictions instinctively.”

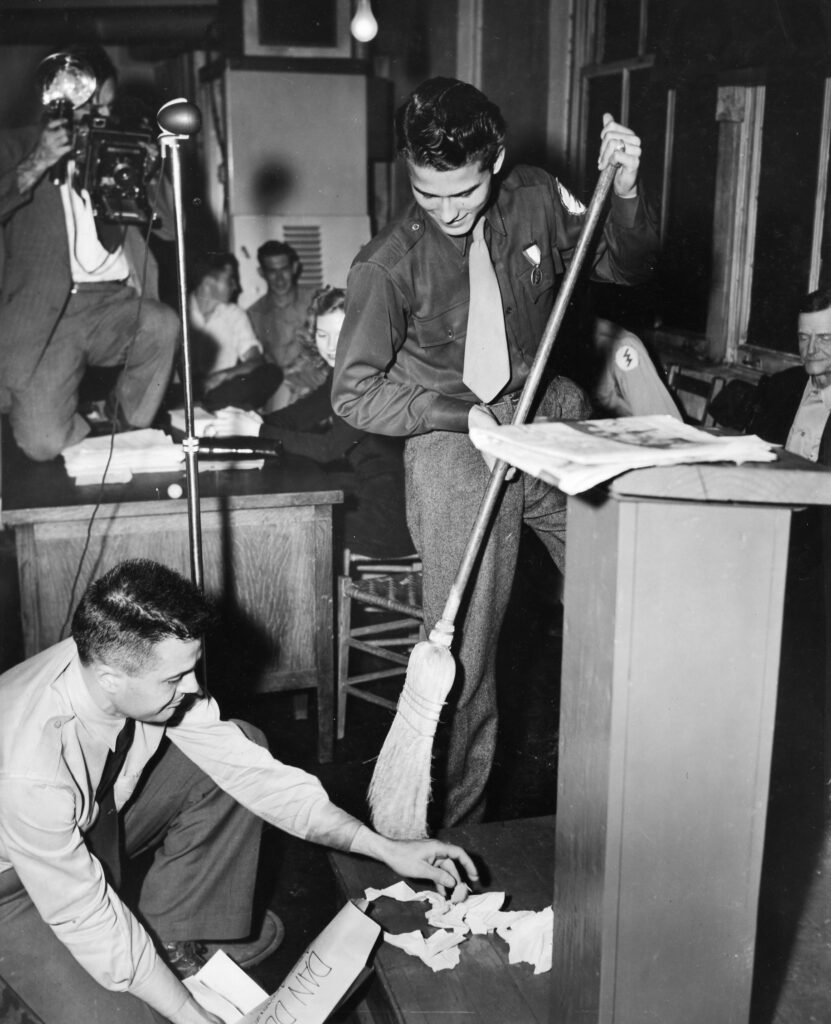

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

In Atlanta, Loomis met Alabama native Emory Burke, who at thirty-one was already a veteran of numerous white supremacist and fascist groups. According to Dan Duke, Georgia’s assistant attorney general, Burke’s name had appeared on the letterhead of “nearly every fascist organization in the country prior to World War II.” Loomis and Burke forged a close personal relationship and, along with a third member, John H. Zimmerlee, of whom little is known, formed the Columbians Incorporated. Describing themselves as a “patriotic and political” group, the three men applied for a charter as a nonprofit organization from the state, which they received in August 1946.

Rise of the Columbians

After receiving their charter, Loomis and Burke stepped up recruitment efforts throughout the city. Though they professed to welcome “all members of the white man’s community,” the two men drew a majority of their support from working-class whites, or as Burke himself put it, “those of our brothers and sisters that many of the politicians call ’poor white trash.'” During weekly meetings at the AFL Plumbers and Steamfitters Union and at impromptu rallies in mill neighborhoods throughout the city, Loomis and Burke warned audiences against the dangers posed by the city’s minorities and urged those gathered to help protect the integrity of white neighborhoods. In order to join, prospective members needed only to fulfill three requirements. “Number one: Do you hate niggers? Number two: Do you hate Jews? Number three: Have you got three dollars?”

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Burke and Loomis claimed to have enlisted as many as 2,000 members, though other sources indicate the actual number was closer to 200. Despite their relatively small membership, however, the group made their presence known. Dressed in khaki uniforms that bore more than a passing resemblance to the Nazi Brownshirts, the Columbians held frequent demonstrations, marching in lockstep through the streets of Atlanta and performing military drills in public spaces.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Neither did their small numbers limit the Columbians’ ambition. Vowing to “show the white Anglo Saxons how to take control of the Government,” Loomis and Burke predicted that the group would win a number of local and statewide elections before making a bid for nationwide control. In order to fulfill their vision of a “progressive white community,” the two men advocated a program of repatriation and deportation for America’s minorities. Under their plan, Black Americans would repatriate to South Africa, which they admitted would first need to be purchased from Britain, and Jewish Americans would be deported to an unspecified location in the Mediterranean. “Briefly,” Loomis explained, “the mission of the Columbians is to separate the white man from the nigger, and the Jew from his money.”

Fall of the Columbians

Their revolutionary posturing notwithstanding, the Columbians generally contented themselves with patrolling transition neighborhoods in lightly armed gangs and roughing up the occasional passerby. Members posted signs that read “Zoned as a White Community” in contested neighborhoods and vowed to use force if necessary to maintain the city’s lines of residential segregation.

The group’s patrols received little attention until the night of October 28, 1946, when a gang of Columbians encountered a young Black man named Clifford Hines walking home through a contested neighborhood. Seventeen-year-old Ralph Childers spotted Hines first, from across Formwalt Street. After a brief pursuit, the group seized Hines and proceeded to beat the young man with a blackjack before police arrived on the scene. The police arrested Childers—and Hines—and the rest of the men were sent home. When bailed out of jail a few days later, Childers received a hero’s welcome and was awarded the group’s medal of honor.

Only five days later, the Columbians again made headlines when Loomis and several other members were arrested for demonstrating at the residence of Frank Jones and his wife, a Black couple who had purchased a home previously owned by whites. In the wake of the two incidents, elected officials, members of the press, and local ministers all condemned the organization as a public menace requiring immediate attention.

In November state officials moved to revoke the group’s charter. Burke welcomed the publicity in statements to the press, but subsequently he received more attention than perhaps he desired. He and Loomis both were indicted on charges of inciting to riot and usurping police powers only two weeks later. Area newspapers cheered their conviction the following February, and state Solicitor General E. E. Andrews concluded that the trial broke the “backbone” of the organization. Indeed, the group’s membership declined precipitously. Burke left the organization to spend more time with his family, and Loomis admitted to reporters in June 1947 that he was the only Columbian left.

A decade later, George Bright, a former member of the Columbians, was arrested and tried for the Temple bombing in Atlanta. He was later acquitted of the crime.

Although the Columbians’ existence may have been brief, their appearance nonetheless dramatized the racial tensions that characterized the postwar South and revealed the anxieties experienced by working-class whites when confronted with the waning significance of their racial privilege. At the same time, the group’s swift prosecution by Atlanta officials demonstrated the efficacy of the moderate consensus that would later earn the city its reputation as “the City Too Busy to Hate.”