During the antebellum period, Georgia and the rest of the South relied heavily on enslaved labor for farming and jobs that required hard labor. But with emancipation and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, slavery as an institution and a form of labor became illegal. After the Civil War (1861-65), landowners had a difficult time finding, and controlling, a labor force.

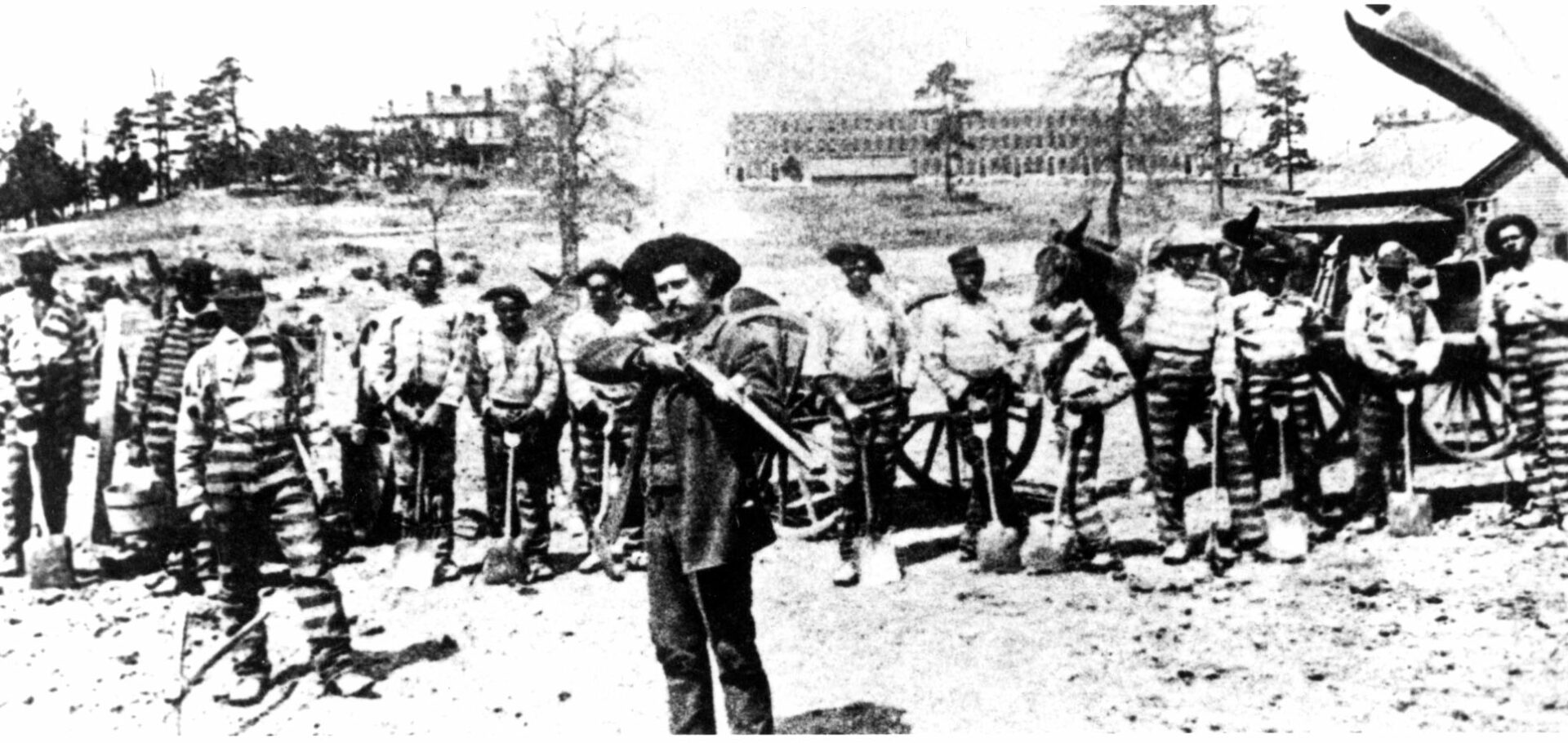

Some Georgians saw the prisoners at the state’s penitentiary in Milledgeville as the solution to their problems—a workforce that could be firmly controlled. Georgia leaders were also concerned about the costs associated with operating a penitentiary, as the prison population increased and included many more African Americans. In an effort to resolve these issues, officials during Reconstruction (1867-76) approved the leasing of prisoners to private citizens.

Provisional governor Thomas Ruger awarded the first convict lease to William A. Fort of the Georgia and Alabama Railroad on May 11, 1868. Fort was given 100 African American prison laborers for one year at the price of $2,500. Fort was responsible for taking care of the prisoners’ basic needs during the year that they were in his possession. Sixteen prisoners died during that first year while working for private entities.

From the government’s point of view, the program was successful. In 1869 the state decided to lease out all of the 393 prisoners in the penitentiary for no fee to the contracting firm Grant, Alexander, and Company to work on the Macon and Brunswick Railroad. Although it was agreed that the convicts would be treated humanely, reports to then-governor Rufus Bullock indicated that leased convicts were being overworked, brutally whipped, and killed while under the care of Grant, Alexander, and Company.

Within five years, convict leasing was a major source of revenue for the state. Over a span of eighteen months in 1872 and 1873, the hiring out of prison labor brought Georgia more than $35,000. With this success, the state legislature passed a law in 1876 that endorsed the leasing of the state’s prisoners to one or more companies for at least twenty years. Three companies took on these convicts at the price of $500,000 to be paid at intervals over the twenty-year span of the lease.

During this period, there were attempts to reform the system of convict labor in Georgia, although such efforts were never successful, in part because of the sheer profitability of the convict lease system. In 1881, expressing intentions to improve the prisoners’ quality of life, the state legislature passed a law requiring that only one person in each work camp be authorized to administer punishment. Rather than ease the difficulties of leased convicts, however, this legislation enabled the harsh treatment of prisoners by men known as “whipping bosses.”

In an 1894 report for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Office of Road Inquiry, O. H. Sheffield, a civil engineer from the University of Georgia, endorsed the utilization of convict labor on state roads. However, because almost all of the state’s 2,000 felons were leased to private companies, only misdemeanants could be used in road construction. In 1903 the state legislature gave counties the opportunity to use felons who were serving less than five-year sentences for roadwork projects.

Convict leasing became less profitable during the first decade of the twentieth century as a rising tide of progressivism, culminating with the election of Governor Hoke Smith, swept across the state. Progressives, influenced by the media exposure of convict leasing’s inhumane conditions, pushed through legislation in 1908 outlawing the convict lease system. This wave of anti–convict leasing was coupled with a depression in 1907, which made enlisting prisoner labor less economically feasible for companies.

When convict leasing was abolished, the use of roadside chain gangs took its place. The chain gang system relied upon the idea that prisoners were repaying their debts to society through labor on public projects, which the state government supported because it could be done “on the cheap.” By 1911 the Georgia Prison Commission reported that 135 of the state’s 146 counties utilized convict labor on road projects.

The chain gang system lasted for several decades. The media, investigators, and prisoners complained of harsh treatment during the course of its implementation. Robert E. Burns’s book I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! , adapted as a film in 1932, brought nationwide attention to the treatment suffered by these prison laborers.

In the mid-1940s the national media focused again on the harsh conditions of Georgia’s chain gangs, which led to a movement to abolish them. Governor Ellis Arnall’s investigation of the prison system ultimately resulted in a prison reform act, which modernized the Georgia prison system and sent chain gangs the way of convict leasing. Convict labor in Georgia no longer endangers the health of prisoners. However, Georgia’s convicts are still expected to work on various projects, including roadside beautification.