In 1936 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) launched a legal campaign to compel the desegregation of southern colleges and universities. After years of litigation and incremental progress in Georgia, the organization earned a landmark victory in January 1961 when U.S. District Court judge William Bootle ordered the admission of Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter to the University of Georgia (UGA). Whether to avoid prolonged court battles or to preserve their academic reputations, Georgia’s other public and private colleges desegregated their institutions in the years that followed.

Background

In the wake of World War II (1941-45), African Americans mobilized in unprecedented numbers to lobby for an end to state-sanctioned segregation. At the vanguard of this movement was the NAACP, and its legal arm, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDF). Under the direction of special counsel Charles Hamilton Houston, the LDF waged a legal campaign to achieve parity between Black and white schools, thereby forcing state governments to suffer the financial pressure of supporting racially bifurcated school systems. Although southern state governments remained committed to maintaining segregation, the LDF won a number of legal victories in the 1940s and early 1950s, moving the courts ever closer to the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision, which declared the concept of “separate but equal” schools unconstitutional.

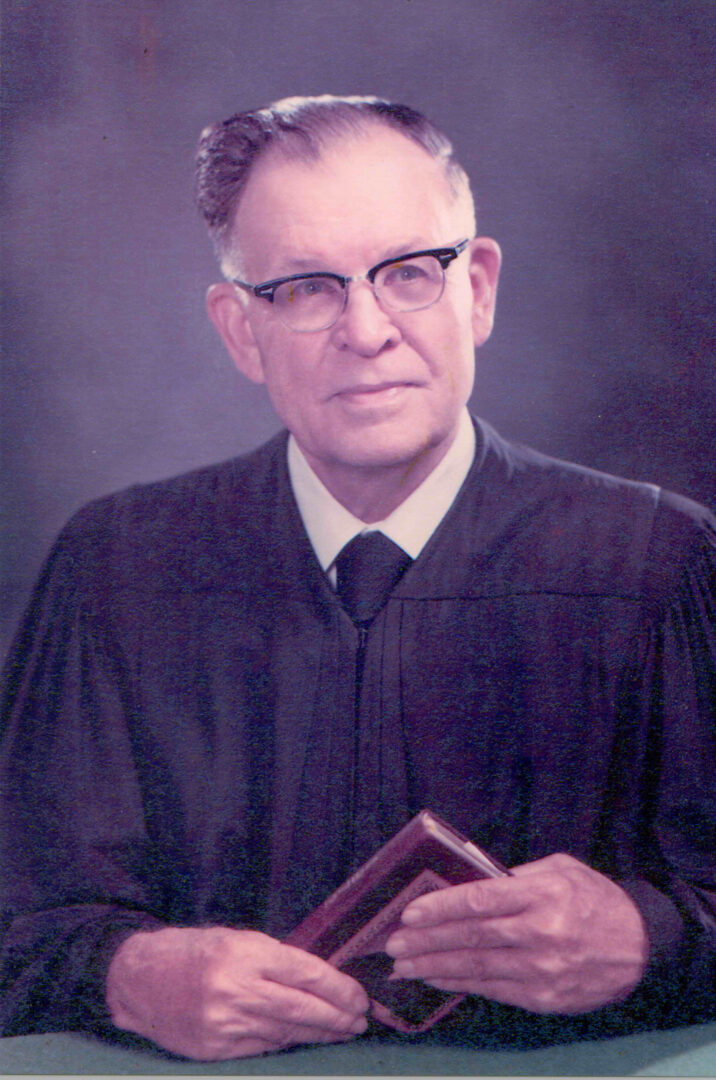

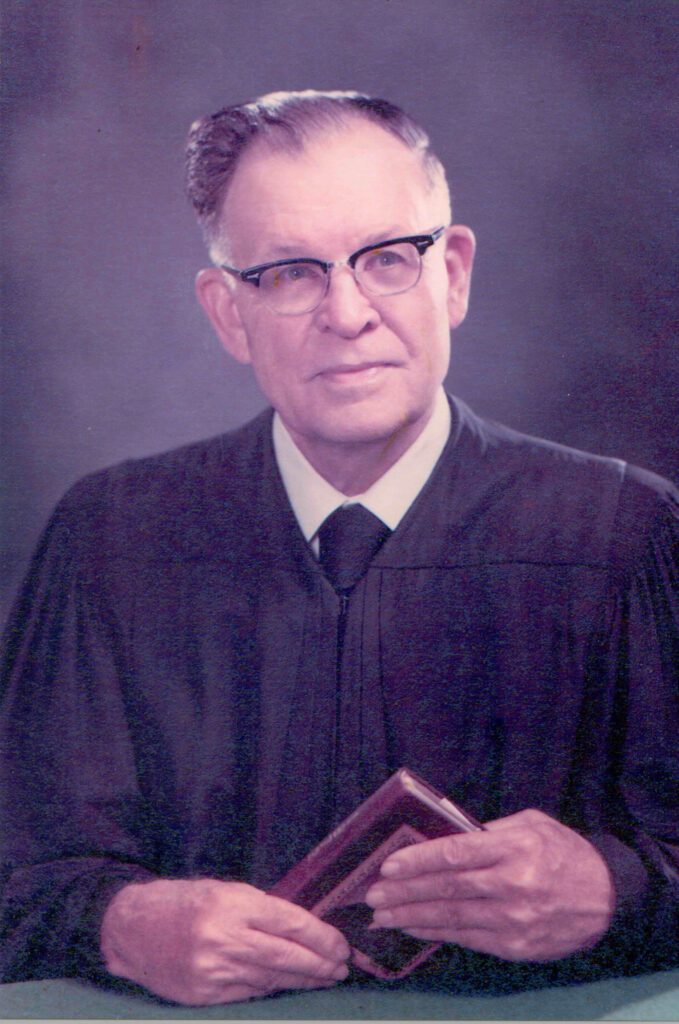

Courtesy of Macon District Court

Of particular concern to the LDF was the provision of equitable graduate instruction to Black students in the segregated South. Because the establishment of separate Black graduate and professional schools represented an enormous financial burden, Georgia and other state governments routinely offered out-of-state tuition vouchers to Black students who wished to pursue a graduate education. In a series of decisions between 1936 and 1950, however, the federal judiciary ruled such practices unconstitutional, and ordered recalcitrant state governments to create “substantially equal” Black graduate schools or admit qualified Black students to state-supported white universities.

Early Desegregation Efforts in Georgia

LaGrange native Horace T. Ward was among a number of Black students emboldened by the Brown v. Board of Education decision. After graduating from Morehouse College, Ward pursued a master’s degree at Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University), where he attracted the notice of William Madison Boyd, the chair of the political science department and president of the state NAACP chapter. Boyd had for some time been searching for a qualified applicant to test UGA’s segregated admissions policy, and had even approached a young Martin Luther King Jr. about applying to the university’s law school, though the future civil rights leader declined, expressing a preference for theology rather than law. Ward, however, was eager to pursue a legal career, and on September 29, 1950, he formally applied to the law school at UGA.

To no one’s surprise, Ward was denied admission. Subsequent appeals were similarly unsuccessful, and the university employed a variety of tactics to prevent future Black applicants from seeking admission to the law school. Under the guise of educational reform, new admissions requirements were adopted by the Board of Regents that required applicants to pass a battery of entrance examinations and to produce additional letters of recommendation, one from a UGA law school alumnus and one from the superior court judge in the area where the applicant resided. The state legislature meanwhile took similar action during the 1951-52 session, passing legislation that called for an immediate cut-off of state funds to any white school that admitted a Black student.

Having exhausted all opportunities for administrative appeal, Ward brought suit in federal district court, alleging that he was denied admission on the basis of “race and color.” For his defense, Ward retained local attorney A. T. Walden, as well as Donald Hollowell, Constance Baker Motley, and NAACP attorneys Thurgood Marshall and Robert L. Carter. Before the trial could begin, however, Ward received notice to report for his induction into the U.S. Army, effectively settling the matter of the university’s integration, at least for the time being.

Although Ward renewed his application in August 1955, after completing his military service, his case did not go to trial until December 1956, by which time he had already enrolled in law school at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Because Ward’s enrollment at Northwestern invalidated his 1950 application to UGA, Judge Frank A. Hooper ruled the suit moot, and dismissed the case. Although they welcomed Hooper’s decision, state officials understood that greater desegregation battles loomed in the distance. In the six and a half years since Ward had applied to the university, the Brown decision had shaken Jim Crow’s legal foundation, making future challenges to segregated higher education all but certain.

Test Case at Georgia State University

In the wake of Judge Hooper’s decision, political observers turned their attention to Atlanta, where three middle-aged Black women—Barbara Hunt, Myra Elliott Dinsmore Holland, and Iris Mae Welch—sought judicial redress after being denied admission to the Georgia State College of Business Administration (later Georgia State University). Although the applicants filed suit in 1956, legal maneuvers kept the case out of court until December 1958, when it appeared on the docket of the federal district court in Atlanta. Throughout the trial, state attorneys maintained that the three applicants were denied admission not because of their race, as was alleged, but because their applications lacked the requisite recommendations from alumni and local officials. The plaintiffs’ attorneys, including Donald Hollowell, meanwhile argued that requiring alumni recommendations represented an unlawful burden for minority applicants because few, if any, of the school’s white alumni would be inclined to recommend the admission of a Black student.

Tensions remained high in the weeks preceding Judge Boyd Sloan’s decision. Although state officials confidently predicted victory, many whites throughout Georgia expressed less certainty and openly debated the desirability of closing all state colleges in the event of an unfavorable outcome. On January 9, 1959, Judge Sloan issued his decision, ruling the state’s admissions policies unconstitutional because it would be “difficult, if not impossible” for Black applicants to obtain recommendations from white alumni. However, because state attorneys successfully discredited two of the three plaintiffs on moral grounds, Judge Sloan balked at ordering their admission to Georgia State, thereby granting the state a measure of latitude to circumvent the decision.

The Board of Regents suspended all admissions to university schools within days of Judge Sloan’s ruling, and later approved a variety of new admission requirements such as personality tests and character assessments that would enable administrators to evade future desegregation efforts. State legislators in the meantime passed a bill imposing age limits on university applicants; under the new guidelines, college admissions would be limited to students younger than twenty-one, while graduate and professional school admissions would be limited to students younger than twenty-five. Although the bill was amended to include numerous exceptions that could be applied to white applicants, it effectively disqualified each of the Georgia State plaintiffs when paired with the reforms passed by the Board of Regents.

The reforms adopted by the Board of Regents were approved despite objections from college administrators who worried that they might adversely affect enrollments and deplete university coffers. Faculty members likewise were concerned that the reputations of Georgia’s colleges would suffer from prolonged resistance to desegregation, and by the late 1950s, polls reflected that a majority of the state’s college students favored token integration over school closings. Intransigence remained the official position in the state capitol, however, even if some legislators privately feared what impact such a course would have on the state’s future.

Breakthrough at the University of Georgia

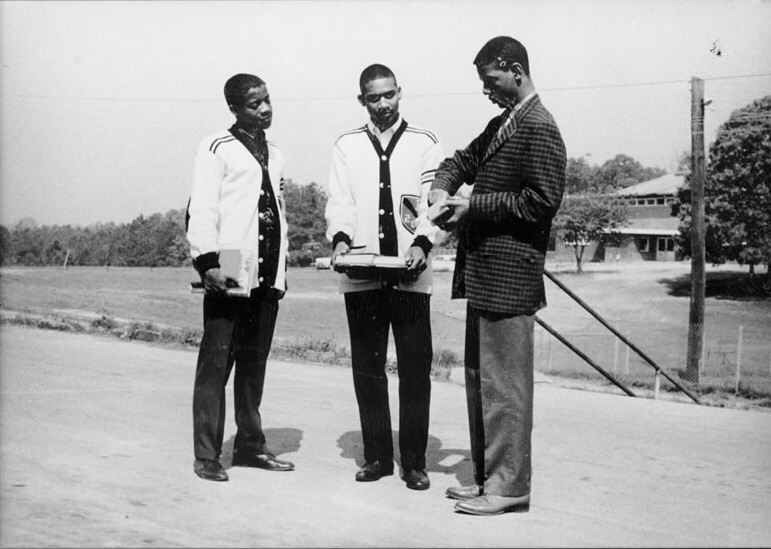

By the fall of 1960 state officials were in court yet again, defending their admissions policies before a federal judge. Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter had applied to the university more than a year earlier, during the summer of 1959, but were informed that the dormitories were filled to capacity and could not accommodate any more students. The pair renewed their applications each semester thereafter, only to be refused admission on each occasion due to “limited facilities.” After exhausting all administrative appeals, the two applicants brought suit, represented by attorneys Donald Hollowell, Constance Baker Motley, Vernon Jordan, and Horace Ward, in federal district court.

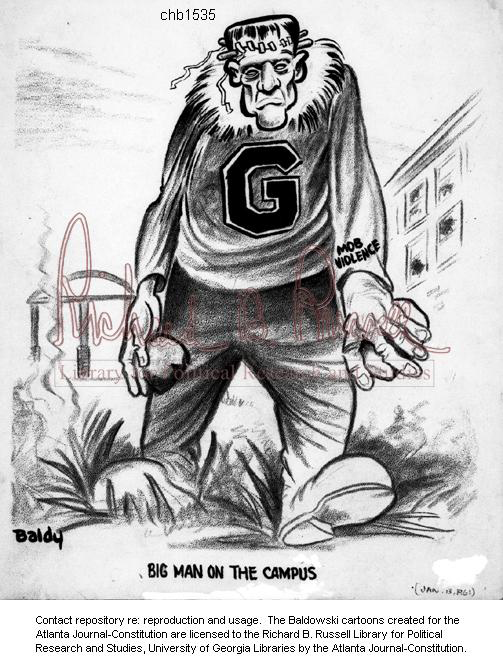

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

Although both Holmes and Hunter possessed unblemished records and were by all accounts model citizens, university officials testified that Holmes had been “evasive” and “inconsistent” during a campus interview, though they admitted Hunter had been “cooperative.” By and large, however, the state’s defense consisted of a series of alleged procedural errors committed by the applicants, to which university officials credited their rejection. Moreover, school officials testified that no policy of segregation existed at any of Georgia’s colleges, and UGA registrar Walter Danner even allowed that he favored the admission of qualified Blacks to the university, despite all evidence to the contrary.

State officials again predicted victory but expected that Judge William Bootle’s decision would not arrive for several months, granting the state ample time to maneuver in the event of an unfavorable ruling. On January 6, 1961, however, a mere three weeks after the trial’s start, Judge Bootle ordered the university to admit Holmes and Hunter, thereby ending 160 years of segregation at UGA.

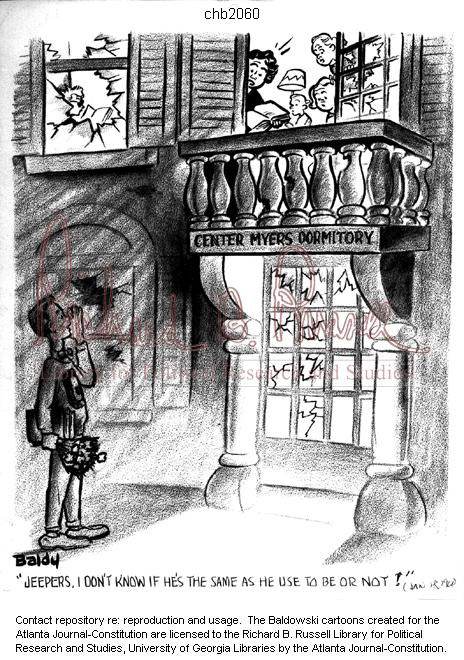

Courtesy of Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies, University of Georgia Libraries.

School officials urged students to remain calm as rumors circulated in Athens and Atlanta regarding the possibility of the school’s closing and as state officials moved to appeal the decision. Order did prevail on campus until several days later, when an angry mob gathered outside Myers Hall, where Charlayne Hunter was now in residence. The rioters, which included students, Ku Klux Klan members, and assorted locals, shouted obscenities, started fires, and lobbed bricks at the dormitory, breaking no less than sixty window panes, including ten in Hunter’s room alone. State troopers were slow to respond, and order was restored only when police used tear gas and water hoses to disperse the crowd.

Although a handful of state officials commended students for their vigorous defense of the state’s white supremacist traditions, most condemned the rioters and called for a return to normalcy. Faculty members expressed similar sentiments at a meeting in the University Chapel the next evening, calling for the reinstatement of Holmes and Hunter, who had been suspended for their own safety and escorted to Atlanta by state troopers following the disturbance. Even Governor Ernest Vandiver Jr., who had campaigned for office on the segregationist slogan “No, Not One,” condemned the mob violence, and perhaps as a result of the negative publicity suffered by the state in the national press, conceded that some integration might be unavoidable.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Judge Bootle ordered the university to readmit both Holmes and Hunter on Friday, January 13, and both students resumed classes the following Monday. Although Holmes and Hunter would both later recall a great deal of unpleasantness during their time at the university, neither was ever again in physical danger on campus. Both students later graduated from the university and went on to enjoy distinguished professional careers. In recognition of their courage and achievements, the Board of Regents voted unanimously to rename the university’s academic building the Holmes-Hunter Academic Building in 2001.

Georgia Tech Follows Suit

The riot at UGA and its aftermath provided a cautionary lesson for Georgia’s other colleges, which hoped to avoid the negative publicity suffered by the state’s flagship institution in Athens. When tensions had subsided there, school officials at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta began planning in earnest for the school’s inevitable integration. Administrators began crafting an “emergency plan” for implementation in the event that large-scale demonstrations or riots developed on campus, and communicated to students that such activity would not be tolerated.

Courtesy of Georgia Institute of Technology Library and Information Center.

In May 1961 Georgia Tech president Edwin Harrison announced that the school would admit three of thirteen Black applicants the following fall. The decision was necessary, he explained, to forestall the possibility of federal intervention and to maintain administrative control over the school’s admissions. Although the decision was greeted with disappointment in certain circles, a majority of student groups, local business leaders, and political figures indicated their support.

Atlanta city officials were meanwhile preparing to meet a court-ordered integration deadline the following fall. On August 30, 1961, two weeks before classes began at Tech, Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield presided over the peaceful integration of the city’s public schools, earning accolades from the national press and alleviating much of the tension that would have otherwise surrounded Tech’s integration. Still, school officials proceeded with caution. Members of the press were barred from campus to discourage disruptive behavior, and plainclothes police officers were on hand to ensure a peaceful registration process. On September 27 the school’s first Black students—Ford Greene, Ralph Long Jr., and Lawrence Michael Williams—attended classes without incident, making Georgia Tech the first institution of higher education in the Deep South to integrate peacefully and without a court order.

Courtesy of Georgia Institute of Technology Library and Information Center.

Integration at Emory University

At the same time Tech welcomed its first African American students to campus, the Board of Trustees at Emory University in Atlanta began serious discussion of the possibilities for desegregation at that institution. Three years earlier, Emory, a private institution, had made its first foray into the politics of school desegregation when 250 faculty members signed a statement of principle in November 1958 supporting the open schools movement in Atlanta. Although Emory remained segregated for the time being, the faculty petition contributed to a groundswell of support favoring token integration rather than the closing of Atlanta’s public schools.

For the Board of Trustees, however, there remained significant legal obstacles to integrating Emory’s campus. Although it repealed laws prohibiting integrated public education in the wake of UGA’s integration crisis, the state legislature left untouched certain measures intended to preserve the racial integrity of the state’s private institutions. According to provisions enacted into state law in 1917, Emory or any of Georgia’s other private institutions of higher learning risked the forfeiture of their tax-exempt status if they admitted both Black and white students. When a qualified Black student applied to Emory’s dental school in the spring of 1962, the school’s administration elected to contest the statute’s legality in court. Lower courts initially upheld the state law, but the Georgia Supreme Court ruled in the school’s favor, upholding Emory’s tax-exempt status, enabling the school to admit its first Black undergraduate in the fall of 1963, and paving the way for the desegregation of Georgia’s other private colleges.

A “Baptist Dilemma” at Mercer University

That Georgia’s colleges were now able to admit Black students did not, however, mean that they were prepared to do so. In October 1962 the Board of Trustees at Mercer University in Macon convened a special committee to study the desegregation issue. Although a majority of the school’s Baptist faculty evinced a willingness to desegregate, student polls were evenly split, and a wide majority of Mercer’s influential law school alumni remained opposed to integration. In January 1963 the committee reported its findings to the Board of Trustees and the Georgia Baptist Convention. “After prayerful consideration,” the report read, the committee had determined that “neither Mercer, nor any other Georgia Baptist institution should adopt such a policy [of desegregation] at this time.”

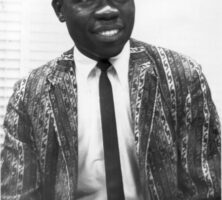

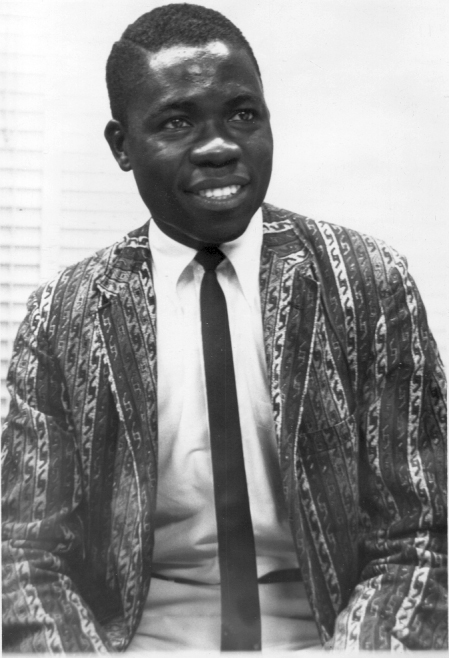

Courtesy of Mercer University

The board’s position became infinitely more complicated, however, when Sam Oni, a twenty-two-year-old student from Ghana, applied to the university. Oni, who had converted to the Baptist faith under the direction of missionaries, was by all accounts a model Baptist and a qualified applicant. He expressed a desire to return home after graduation to help spread the Baptist faith, and his application benefited from the support of Harris Mobley, a Mercer alumnus undertaking missionary work in Africa.

For members of Mercer’s Board of Trustees, Oni’s application presented what historian Alan Scot Willis termed “truly a Baptist dilemma”: could university officials accept students from foreign missionary fields while maintaining a policy of exclusion toward African Americans at home? Although many officers and laypeople in the Georgia Baptist Convention recommended doing just that, a majority of members recognized the basic contradiction inherent in such a position. After months of careful consideration, the board voted in April 1963 to admit Oni and to abolish all racial restrictions in admissions to the university.

Berry College and Beyond

When he arrived on campus the following fall, Oni joined one of a growing number of private institutions across the South that elected to desegregate without a court order. Colleges that delayed undertaking similar reforms soon discovered that other pressures could be brought to bear on their decision making. When John R. Bertrand, president of Berry College in Rome, announced in September 1964 that Berry had admitted three Black students who would begin classes that fall, he cited financial pressures among the factors motivating his decision. Title VI of the recently passed Civil Rights Act (1964) stipulated that only institutions with open admissions policies were eligible for federal grants, and Berry and other colleges delayed integration at their own financial peril.

Desegregation efforts in Georgia took an unexpected turn in 1972, when twenty-nine white citizens living in the vicinity of Fort Valley filed a lawsuit against Fort Valley State College (later Fort Valley State University), alleging that the historically Black school discriminated against whites in admissions and hiring practices. Although the case was rooted in a desire to dilute the voting strength of the Black college community, Judge Wilbur Owens nonetheless ordered the Board of Regents to submit a plan for the school’s desegregation. Small numbers of white students enrolled at Fort Valley in the years that followed, but the school remained a predominantly Black institution.

On March 27, 1973, only five days after Judge Owens issued his ruling in the Fort Valley case, the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare ordered the Board of Regents to submit a plan for the complete desegregation of the colleges and universities of the University System of Georgia. Over the course of the next several years, the board submitted a series of plans that failed to meet the expectations of federal authorities. But in 1983, a full decade after the original order, the board secured federal approval for its revised plan, and by 1988 the university system had finally met all the requirements of that agreement.

Although in 2007 African Americans accounted for one quarter of total student enrollment throughout the university system, they remain underrepresented at many of the state’s prominent public universities, particularly at its flagship university in Athens. Recent efforts by the school’s administration notwithstanding, in 2007 minority enrollment only inched past 17 percent, and African Americans accounted for just 6.8 percent of UGA’s student body. Charlayne Hunter-Gault lamented the underrepresentation of Blacks when she returned to Athens in 2001 to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of the school’s integration. “If anyone had given Hamp [Hamilton Holmes] and me a crystal ball into which we could have looked to the future forty years hence and seen only 6 percent students of color,” she reflected, “I think we might have sat down under the Arch and cried.”