Before Georgia had roads, it was laced with Indian trails or paths. These trails served the needs of Georgia’s native populations by connecting their villages with one another and allowing them to travel great distances in quest of game, fish, shellfish, and pearls, as well as such mineral resources as salt, flint, pipestone, steatite, hematite, and ochre. Many groups followed an annual economic cycle that saw them undertake seasonal migrations in pursuit of plants and animals needed for their existence.

Travel for war making was also dependent on trails leading to the homelands of hostile groups. To take to the warpath had more than metaphorical meaning to Georgia’s Indians. The first map General James Oglethorpe selected to publicize his newly founded colony was based on the work of Thomas Nairne, a trader-explorer and Indian agent. It showed several important Indian trails, including “the Road of the Ochese [Creeks] going to War with the Floridians.”

Origin

There is abundant evidence indicating that some of the trails used by the early Indians of Georgia were already formed by large grazing animals, particularly buffalo. These animals ranged through much of Georgia and the Southeast until they were hunted to extinction in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. Nairne wrote of hunting them in his excursions across the Southeast in the first years of the eighteenth century. He noted that the paths leading to the clay pits or licks, at which buffalo congregated, were as numerous and “well Trod” as those leading to “the greatest Cowpens in Carolina.” The best known of Georgia’s buffalo licks was described by the naturalist William Bartram and is located about ten miles south of Lexington in Oglethorpe County. It was a prominent point along the trail followed by Bartram in 1773.

Arrival of the Spanish

In 1526, after making landfall in South Carolina and finding it an unpromising place for a settlement, Georgia’s first colonizer, Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón, with a large party of horsemen and infantry, followed Indian trails south to Sapelo Sound in Georgia. Here he reunited with his ships, the rest of his 600 colonists, including women, children, and enslaved laborers, and farm animals to establish the first colony of Europeans and Africans in Georgia. After Ayllón’s premature death, the colony failed, and only about 150 survivors made their way back to Spanish settlements on Caribbean islands.

Fourteen years later the would-be conquistador of the Southeast, Hernando de Soto, followed Indian trails into Georgia from his winter encampment in present-day Tallahassee, Florida. De Soto and his army depended on the food they could take from the Indians, so their route took them along trails that connected Indian villages. Failing to follow local advice, the Spaniards encountered trouble when they foolishly headed into unpopulated stretches where no trails or villages were to be found; this happened to de Soto as he was crossing into South Carolina from Georgia in a fruitless and nearly fatal search for treasure and gold.

Indian Trails in Colonial Georgia

Two centuries later, when Oglethorpe was laying out the new colony of Georgia, Indian trails were of even greater importance. For example, in 1734, when Oglethorpe laid out the town of Ebenezer for a large group of German Protestant settlers, he ignored the site’s lack of agricultural potential and based his choice on the fact that it was located where a number of Indian trails converged at a crossing on Ebenezer Creek. After two years of struggling to survive in this poor location, the settlers were allowed to move to a new location with better soil.

Oglethorpe followed a similar strategy emphasizing transportation when he ordered the building of Augusta in 1736. His motive was to intercept the lucrative Indian trade at the point where a complex of major Indian trails from the interior Indian country reached the head of navigation on the Savannah River just below the fall line. Previously this trade had been enriching the merchants and traders of South Carolina. Three years later Oglethorpe wrote of Georgia’s successful trading outpost: “The settlement of Augusta is of great service, it being 300 miles from the Sea and the Key of all the Indian Countrey.” Augusta diverted first deer hides and later upland cotton away from Charleston to Savannah’s warehouses and wharves, eventually exceeding even its founder’s most optimistic dreams.

Native Americans came to realize the strategic importance of their trails and at times were reluctant to allow whites to survey or map them. In 1772 David Taitt, a deputy Indian agent, recounted that when on the trail in the Creek country he placed his servant between himself and his Indian guide, “thereby preventing him from seeing me take observations of the course of the path and creeks we passed.” At other times Taitt hid his compass on his saddle and surreptitiously took the courses of the trails he was following so as not to offend his Indian hosts.

Siting and Marking

Native Americans tended to avoid difficult terrain as they traveled across wide stretches of Georgia’s early landscape, and as a result Indian trails generally followed ridges and drainage divides to minimize stream crossings and swampy bottomlands. Later, engineers used the same criteria when laying out and constructing railways and roads. Bridges were costly to construct and hard to maintain, so the routes pioneered by the Native Americans were often later overlaid by iron rails and graveled roads. When large creeks and rivers couldn’t be avoided, the Indian trails often led to rocky shoals or shallows that could be easily crossed or safely forded. In times of high water travelers sometimes carried collapsible wooden frames and covered them with hides to provide small portable boats for crossing. Dugout canoes were sometimes hidden for use in crossing, or rafts or hickory or elm bark canoes were made on the spot. Before their forced removal along the Trail of Tears, a number of Cherokees operated ferries across north Georgia’s larger rivers.

Nairne told of how the Native Americans, when pursued, would remove and hide their canoes to foil their pursuers, who could not cross large rivers after them. He also mentioned seeing the Indians use “rafts made of Dry wood or canes” and “small Bark canoes”and even bearskins or large deerskins stretched on frames to float such perishables as gunpowder while an Indian swam along guiding it. On his map Nairne included this caption near the center of the Florida peninsula: “Here the Carolina Indians leave their Canoes when they goe to War against [the] Floridians.”

Some Indian trails were marked with signs. Philip Thicknesse, a contemporary of Oglethorpe’s, wrote of walking in the woods near the head of the Savannah River and finding “tied to a Tree a Bit of… Cedar, on which, in a very uncouth Manner several Figures were delineated.” According to Thicknesse, Upper Creek warriors who had been traveling on the trail placed the cedar tablet. It was intended to announce and memorialize the loss of two members of their party. Even earlier, in 1674, Henry Woodward, called the first settler to South Carolina, reported seeing several times along the trails he followed “[where] these Indians had drawne uppon trees (the barke being hewed away) [the] effigies of a [beaver], a man on horseback and guns.” Woodward was looking forward to trading with the Native Americans and chose to interpret these signs as indicating “their desire for freindship and comerse with us.”

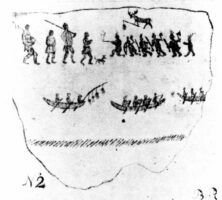

In 1775 Bernard Romans reproduced similar trail messages in his book, A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida. The naturalist Mark Catesby, who visited Georgia forty years before Bartram, also described trail marking. Catesby wrote that the Indians would “leave certain marks in the way, where they that come after will understand how many have passed and which way they have gone.” William Gerard De Brahm, one of Georgia’s royal surveyor generals of lands and the former employer of Bernard Romans, told of how he also found Indian-drawn “hieroglyphics” in red and black on trees along Indian paths. To De Brahm’s eye they were “executed with so much Art, as those, that appear on the Coffin of the Egyptian Mummies.”

At a point where several trails met about six miles east of present-day Clarkesville stood a large tree that tradition says was called “Chopped Oak.” It was on the summit of a ridge and, according to the early settlers, the Cherokees assembled there. Gashes cut in the tree were, according to ethnologist James Mooney, “tally marks by means of which the Indians kept the record of scalps taken in their forays.”

Trails as Boundaries

An indication of the importance of Georgia’s early Indian trails is the frequency with which they served as boundaries to separate the lands of the whites from the Native American hunting grounds. In 1763 an important boundary treaty was signed at Augusta with “the Kings, Headmen, and Warriors of the Chicasahs, Upper and Lower Creeks, Chactahs, Cherokees, and Catawbas.” In the treaty the “Lower Creek Path” and “the path leading from Mount Pleasant” were designated to mark parts of the boundary. In 1773 another, even more important, treaty with the Creeks and Cherokees established the Indian boundary along the trail leading to the buffalo lick that William Bartram described so colorfully in his Travels. When Wilkes County was created out of that Indian land cession, “the old Indian line” marked its western boundary.

Modern Maps

Georgia scholars John H. Goff and Marion R.Hemperley devoted much of their research to efforts aimed at mapping early Indian trails and trading paths. When first seen their maps strongly resemble modern state highway maps. It is only since the post–World War II (1941-45) period that the widespread use of heavy construction equipment has allowed the landscape to be radically altered in order to build straighter and less-hilly routes for trucks and automobiles. But when the automobile era dawned in Georgia, most roads were a bit wider but otherwise little changed from the Indian trails that preceded them. In writing about Indian trading paths across the Georgia Piedmont, Goff observes, “This network was comparable to today’s highway system in that it consisted of both local and arterial routes.”

A study of the Goff and Hemperley trail maps quickly reveals some striking regional differences. Notably few trails were found below the fall line, where the many broad, slow-flowing rivers and creeks allowed the easy use of dugout canoes for travel and trade. The trail system was most dense in the Piedmont, where streams were swifter and frequently interrupted by shoals and rapids that could be made hazardous by flooding. Georgia’s earliest white pioneer settlers were quick to perceive and seize on the opportunities these trails provided. In applying for their land grants the settlers exhibited a strong preference for sites located along major trails. It was a further bonus when the grant contained land formerly occupied and cleared by Indians, known as “Indian old fields.” So important were Indian trails that when Georgia became a state, the surveyor general ordered that all land surveyors “insert in their proper places, what runs of water… noted paths or roads” their survey lines crossed. When they constructed their maps of Georgia’s early Indian trails, both Goff and Hemperley relied heavily on original land survey plats that showed these features.