Jews have lived in Atlanta since its founding. Their businesses met important economic needs, and they contributed substantially to the cultural, educational, and political well-being of the society. Their history also reflects a rich cultural diversity not typically recorded in southern history.

Most of Atlanta’s Jews were immigrants, having lived in other areas of America before migrating to the city. Yet theirs was not necessarily a random movement. They tended to travel in chains of migration following earlier relatives or landsmen—people from the same areas of Europe—to locations that offered the greatest likelihood of mercantile success and, ultimately, in which they could establish Jewish community institutions. Atlanta’s Jews epitomized the New South creed four decades before Henry Grady proclaimed it. Starting as peddlers or in partnerships with relatives and friends, they obtained dry goods on credit from northern wholesalers (especially those in Baltimore, Maryland, and New York City). Often selling cheaply and on credit, the Jewish community opened a consumer window and thus filled a critical economic niche as merchants.

Economic and Religious Beginnings

From the mid-1800s Atlanta proved to be one of the best locations in the South for Jews. In 1850 twenty-six Jews lived in Atlanta. Though they constituted just 1 percent of the city’s total population of 2,572, they owned more than 10 percent of its retail businesses. Almost all of the people were immigrants from central Europe, mostly the Germanic states. Although by the eve of the Civil War (1861-65) the Jewish population in Atlanta had doubled, their small numbers still precluded the establishment of formal religious institutions. Religious services were held intermittently, and women offered religious classes for children. The Hebrew Benevolent Society, which was started in 1860 and provided insurance, aid, and burial benefits, served as the first formal Jewish religious organization and the forerunner of things to come.

The Jews of Atlanta had been welcomed with little prejudice and had fit into society. A few owned enslaved people, some employed enslaved workers in their business pursuits, and most supported the Confederacy. David Mayer, the most noteworthy of the Confederacy supporters, served as Georgia governor Joseph E. Brown’s commissary officer. Yet Reconstruction affected Jews differently than most southerners. As merchants, the Jewish community reestablished ties with northern businesses and quickly recovered. Their numbers also dramatically increased with the arrival of numerous immigrants who had previously resided elsewhere in the South or North. From Cleveland, Ohio, for example, came Morris Rich, who, with his brothers, built the retail business that became Rich’s Department Store. By 1880 Atlanta was home to 600 Jews.

The rapid influx of Jews contributed to the creation of religious institutions. On January 1, 1867, the Reverend Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, presided over the first Jewish wedding in Atlanta, that of Emilie Baer to Abraham Rosenfeld, and used the occasion to encourage the creation of a congregation to replace the short-lived one begun in 1862. The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation received a charter four months later and began constructing a synagogue in 1875.

During the next two decades the congregation swung back and forth between traditional and Reform Judaism, hiring and firing rabbis as first one faction and then the other gained power. The rabbis frequently supplemented their salaries by heading an English-German-Hebrew Academy, which provided classes before the creation of a public school system and which reflected pluralistic identity. The arrival of American-born David Marx, who was trained at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Ohio, symbolized an end to much of the controversy. The congregation, now called “the Temple,” adopted Reform practices and beliefs more acceptable to middle-class America and its acculturating Jews. Marx also served as “ambassador to the Gentiles,” the unofficial voice of the Jewish community.

As befit their socioeconomic status and their cultural norms, Atlanta’s Jews participated in public life. Active in the conservative faction of the Democratic Party, Jews routinely held seats on the aldermanic board, the school board, and in the state legislature. David Mayer, for example, was a founding and longtime member of Atlanta’s school board. In 1875 Aaron Haas became the city’s first mayor pro tempore. Joseph Hirsch and other Jews led in the establishment of Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital.

Influx of New Immigrants

Beginning in 1881 Atlanta lured Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe and, after 1906, a small enclave from the crumbling Ottoman Empire. The newcomers obtained assistance from their predecessors and created their own institutions. Congregation Ahavath Achim was founded in 1887 followed by Shearith Israel (1902), Anshi S’fard (1913), and Or VeShalom (1914), a Sephardic synagogue.

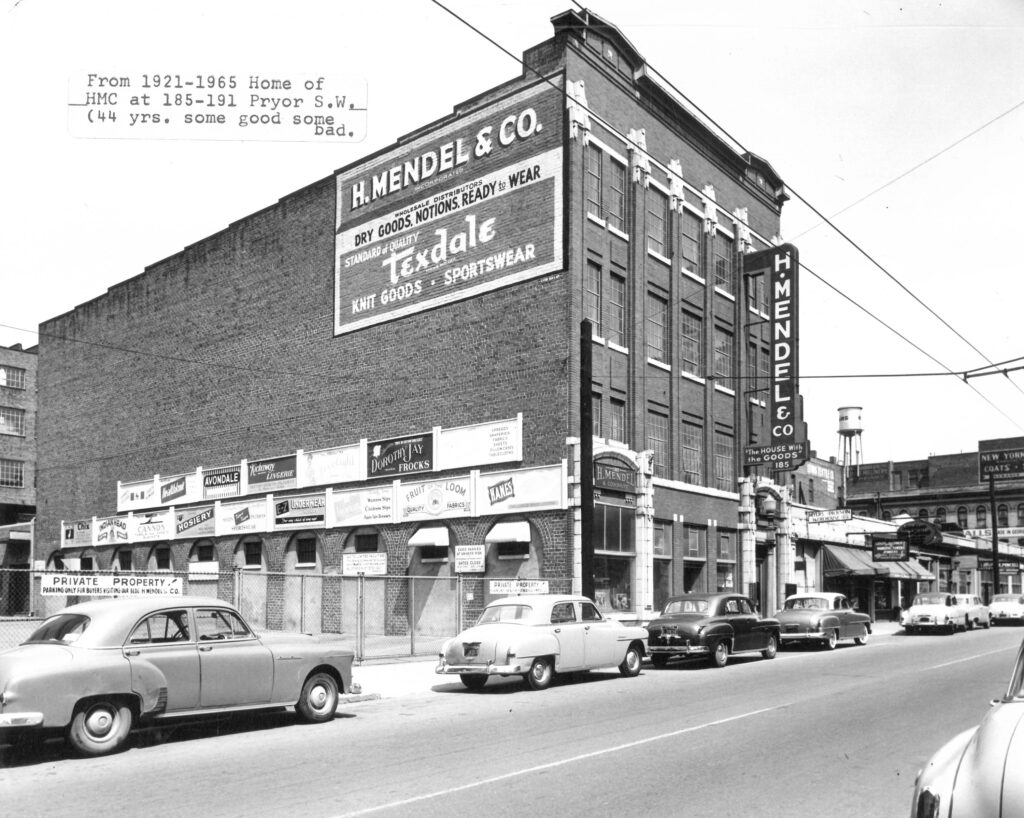

Unlike their counterparts in industrial metropolises but following the example of the previous Jewish immigrants to Atlanta, few of the newcomers entered the factories. Instead they made their livelihoods through small-business enterprises. To raise capital they started as peddlers, obtained goods on credit, worked as clerks, created partnerships, and/or obtained funds from the Montefiore Relief Association, Free Loan Association, or Morris Plan banks, where a reference’s signature replaced collateral. Success stories like that of Hyman Mendel, who became the city’s biggest dry-goods wholesaler, abounded. Real-estate investments and, for the second generation, professional careers opened other doors upward. Ben Massell, for one, became one of Atlanta’s premier builders and developers during the mid-twentieth century. In 1969 his nephew, Sam Massell, was elected mayor of Atlanta.

Intragroup relations were often divisive. The old-timers were frequently condescending toward the greenhorns who spoke Yiddish or Ladino, followed traditional religion, supported Zionism, and began in the lower class. Besides the differences, the newcomers were also concerned with the possibility of an anti-Semitic backlash that could undercut their acceptance.

During the nineteenth century Atlanta’s Jews created social clubs as well as self-help organizations, including men’s and women’s Hebrew Benevolent Societies. The Concordia Society, forerunner of the present Standard Club, was a Jewish social organization founded in 1866. A local chapter of the Jewish fraternity B’nai B’rith opened its doors in 1870.

The arrival of the new immigrants, coupled with the declining needs of the earlier immigrants, contributed to the transformation of Jewish social services and club life. David Marx had encouraged his women congregants to form a local section of the National Council of Jewish Women (1895). This organization aided Jewish immigrants and nurtured their Americanization through classes, particularly under the auspices of the Free Kindergarten and Social Settlement (1903). The Federation of Jewish Charities, later a charter member of the Community Chest (United Way), started as an umbrella organization in 1905 to rationalize fund-raising and the delivery of assistance and then reorganized in 1912. It included the women’s organizations as well as the Jewish Educational Alliance (1909), a settlement-type entity, and the Free Loan Association. The federation board included women and representatives of the eastern European and Sephardic communities.

Gradually this interaction, along with the rise and acculturation of the newer immigrants, especially after the closing of America’s doors to immigrants during the 1920s, contributed to the decline of animosity. Nonetheless, the eastern Europeans, refused acceptance into the Standard Club, organized the Progressive Club (1913). In 1917 a local chapter of Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization geared toward medical and educational assistance, began. Although each of a series of rabbis—from Marx to Harry Epstein, Tobias Geffen, and Joseph I. Cohen—served Atlanta’s major congregations for decades, and Marx and Victor Kriegshaber, the most influential Jewish layman after David Mayer, led in the formation of these organizations, the federation ushered in a power shift to the executive directors, starting with Edward M. Kahn in 1928.

Decades of Transformation and Unity

The Great Depression only temporarily delayed Jewish movement into the middle and upper classes. Nonetheless the 1930s still marked a watershed. New Deal agencies alleviated the need for private charity, and anti-Semitism at home and Adolf Hitler’s policies in Germany resulted in a switch in priorities to overseas relief. A critical meeting chaired by Coca-Cola Company attorney Harold Hirsch in 1936 resulted in another reorganization of Atlanta’s Jewish social service agencies. The Jewish community coalesced to raise funds and combat discrimination more effectively than at any other time in its history. During and after World War II (1941-45), although Marx continued his battle against a Jewish state, the tide turned toward support for Zionism. This was dramatized with the creation of Israel, during its war for independence, and subsequent conflicts through the 1970s that nurtured changing senses of identity and pride.

The mid-1940s to 1950s witnessed the beginning of Atlanta’s coming of age as a center of southern Jewry. Everything was planned. A population study (locating 9,630 Jews) was undertaken, experts were consulted, and a community calendar was established. Most of the congregations and the Jewish Community Center, successor to the Jewish Educational Alliance, launched building drives. Jewish Children’s Services replaced the Hebrew Orphans Home, which had been created by the B’nai B’rith fifth district lodge in 1889. A Jewish old-age home (1951) was created as was the Bureau of Jewish Education (1946) and the Hebrew Academy (1953). Local or regional chapters of the American Jewish Committee, the Anti-Defamation League, the Jewish Welfare Board, and the Zionist Organization of America made Atlanta their home. The creation of Orthodox Congregation Beth Jacob, soon under the leadership of Emanuel Feldman (1952), served as a harbinger of the ceremonial/religious revival of the last half of the twentieth century.

Jews, African Americans, and Prejudice

Some historians argue that prejudice against African Americans shielded Jews in the South from discrimination. Certainly this is the case in comparison with American racism and European outbreaks against the Jews culminating in the Holocaust. Yet Jews and African Americans have been linked ambiguously in the South since the mid-nineteenth century, and the eras of the greatest racism coincide with the rising specter of anti-Semitism.

In Atlanta, as elsewhere, some Jewish peddlers, merchants, and landlords conducted business with African Americans, often extending credit and courtesies contrary to common usage. Jews also were the first to hire Black workers as clerks and in other positions. These not only were good business practices but also reflected a sense of association brought about by similar historical experiences of persecution. Although the Jews were in a better position to become upwardly mobile, Jewish immigrants and African Americans shared poverty and resided in the same neighborhood during the early twentieth century. At the same time, more-affluent Jews employed African Americans as domestic servants. The empathetic/patronizing nature of such relationships was dramatized in Roy Hoffman’s novel Almost Family (1983) and Alfred Uhry’s play Driving Miss Daisy (1987).

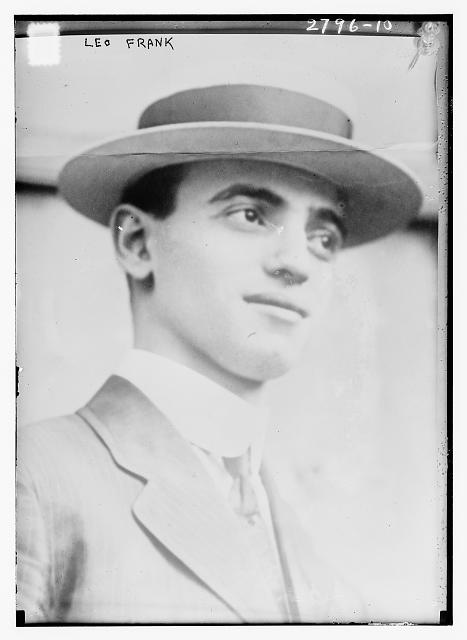

The Atlanta race massacre of 1906 and a series of strikes against the Elsas family’s Fulton Bag and Cotton Company, at one time the city’s largest industrial employer, formed part of the backdrop for the Leo Frank incident, possibly the most dramatic case of anti-Semitism in American history. In 1913 Frank, a Jew raised in New York, was accused of murdering Mary Phagan, an employee of the Atlanta pencil factory he managed. Frank was convicted in a sensational trial largely on the testimony of a black janitor, Jim Conley, something virtually unprecedented in the Jim Crow South. Through his trial and appeals Frank was caricatured as the northern businessman and Jew out to exploit young women from the rural South. After the commutation of his death sentence to life in prison by Governor John M. Slaton, who believed him innocent, Frank was abducted from prison and lynched by citizens of Marietta, Phagan’s hometown. Frank received a posthumous pardon in 1986. The case contributed to the founding of both the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith and the Knights of Mary Phagan, a forerunner of the modern Ku Klux Klan. In 1915 Kriegshaber was elected president of the chamber of commerce, possibly in partial atonement for the Frank incident. Yet the lynching shattered the sense of security felt by Atlanta’s Jews, who were routinely excluded from the city’s elite social clubs. During the succeeding decades Jews were attacked by the Klan, the Columbians, and other right-wing groups. They were tolerated but also singled out as different.

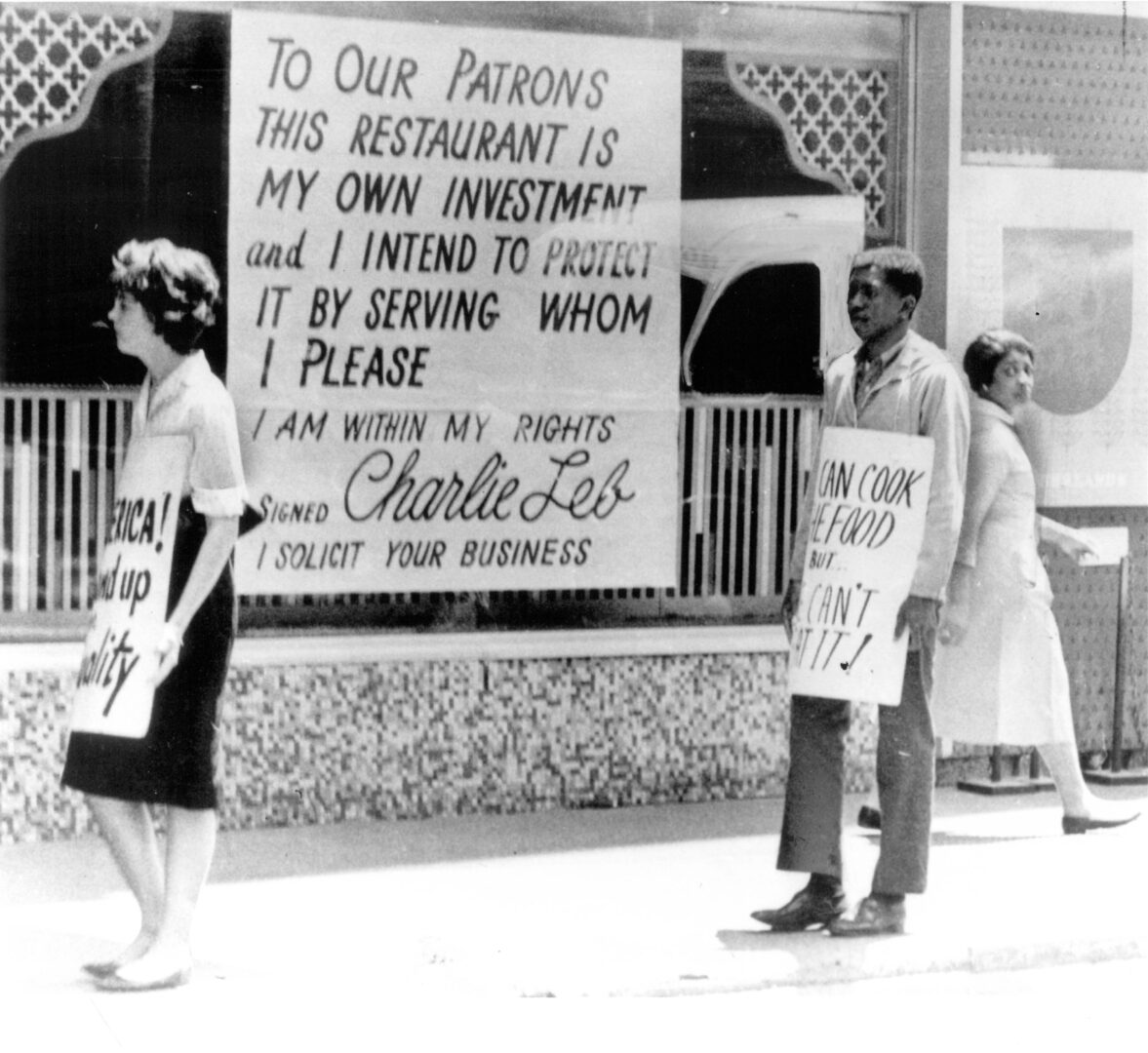

Although most Atlanta Jews remained silent concerning black rights—the majority out of fear, but some out of acceptance of southern racial mores—a few condemned discrimination during the 1920s and 1930s, especially through the Atlanta Urban League. When Marx’s successor at the Temple, Jacob Rothschild, provided leadership against discrimination, in 1958 the synagogue joined the ranks of those bombed. Unlike the Frank case, strong condemnation of the Temple bombing by Mayor William B. Hartsfield and Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill, and dramatic community support, helped the wounds heal quickly. On the other hand, when Rich’s Department Store and Leb’s delicatessen were singled out by sit-in demonstrators during the early 1960s, the latter became a symbol of recalcitrance. Still, thereafter black-Jewish relations seemed to remain more positive on the local level than nationally, as partly reflected in the establishment of the Atlanta Black-Jewish Coalition (formed by architect Cecil Alexander and civil rights leader John Lewis) and numerous examples of positive interaction in government, and in 1962 doctors Irving and Marvin Goldstein built the Americana, the first integrated hotel in the city.

To the Present

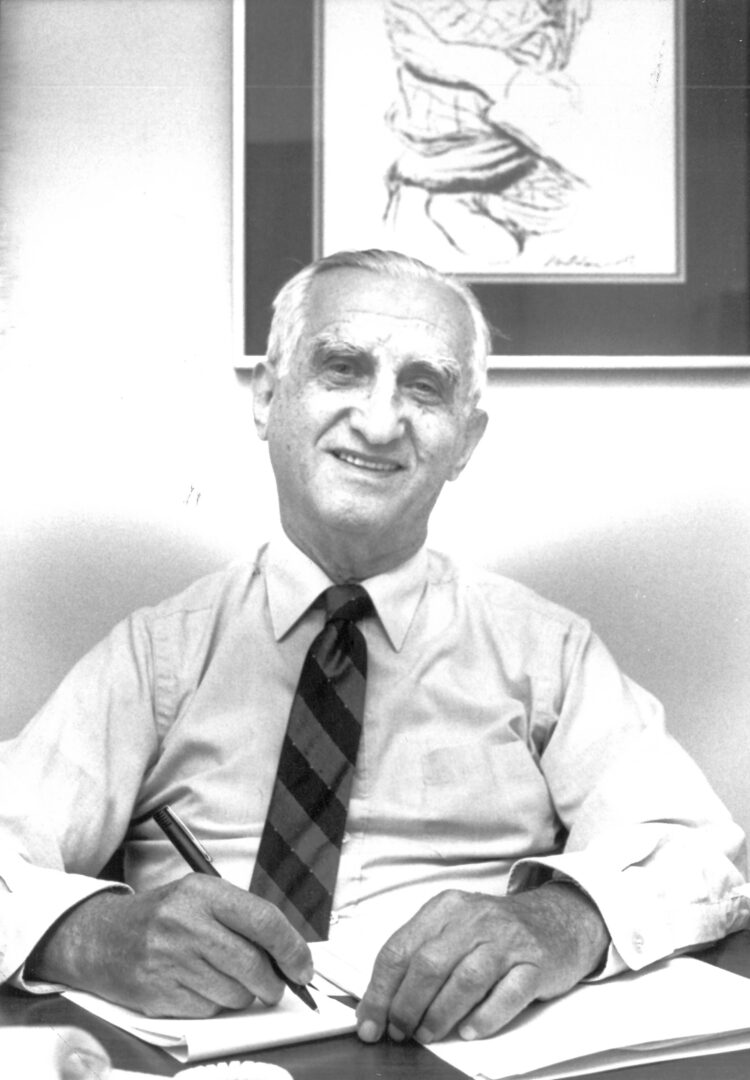

The Atlanta Jewish community grew tremendously during the last quarter of the twentieth century. Small numbers of immigrants from Russia, Iran, Israel, and South Africa entered the metropolitan area and were joined by numerous transplants from the North and elsewhere in the South. By 1992 the Jewish population was estimated at more than 70,000. A decade later the metropolis served as home to about twenty-five synagogues, seven Jewish day schools, and the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum. The federation reorganized in 1967 under Max C. “Mike” Gettinger and still again under David Sarnat during the 1990s to meet changing needs. Many of Atlanta’s Jews participate in numerous programs to visit Israel. Extremely active in the professions and in business, education, politics, and the arts, they contribute to the pluralistic nature of the community.