A chemist, geologist, and instructor, John Ruggles Cotting conducted a significant geological survey of Georgia’s Burke and Richmond counties in 1836. As the first state geologist of Georgia, he completed a study in 1839 of the topography, geology, mineral resources, and soils in more than two dozen counties. Although Cotting diligently performed his duties, a series of obstacles prevented the publication of his work, which remains lost to Georgians today.

New England Years

Born on November 16, 1784, in Acton, Massachusetts, to Elizabeth and William Cutting, John Ruggles Cutting altered the spelling of his surname to Cotting in 1811. After graduating in 1802 from Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, he prepared for the Congregationalist ministry. In 1807 he married Sally Stone of Concord, Massachusetts, with whom he had two children: Susan, born by 1811, and David, born in 1812. Also in 1807, Cotting was ordained as pastor of the Congregational Church in Waldoborough, Maine, but he resigned that position in 1811.

Cotting served briefly in 1812 as a chemist for a firm in Boston, Massachusetts, after which he became an instructor. Between 1813 and 1827 he taught in several Massachusetts towns and cities, including Amherst, Boston, Brookfield, Dedham, and Pittsfield. While at Amherst Academy in 1826, he served as editor of The Chemist and Meteorological Journal. Little is known of his career between 1828 and 1835. His wife Sally died in the late 1820s, and around 1830 he married Mary Metcalf, of Dedham. With his second wife, he had two children: Cassandana, born in 1832, and William, born in 1839.

During his years in New England, Cotting published two books: An Introduction to Chemistry, with Practical Questions (1822) and A Synopsis of Lectures on Geology (1835). Abreast of knowledge and theories about the earth’s history, Cotting was among the first Americans who endeavored to reconcile the evidence of an ancient earth with the biblical account of creation.

Georgia Geological Surveys

Cotting’s book on geology probably caught the eye of planters and businessmen in Burke and Richmond counties who believed that an agricultural and geological survey of their counties could lead to improvements in crop production and to economic progress in the region. Unlike several other states, Georgia had not established a state geological survey, so the enterprising citizens of Burke and Richmond decided in 1835 to proceed on their own. They invited Cotting to do the study, and late that year he and his family moved to Augusta, the seat of Richmond County.

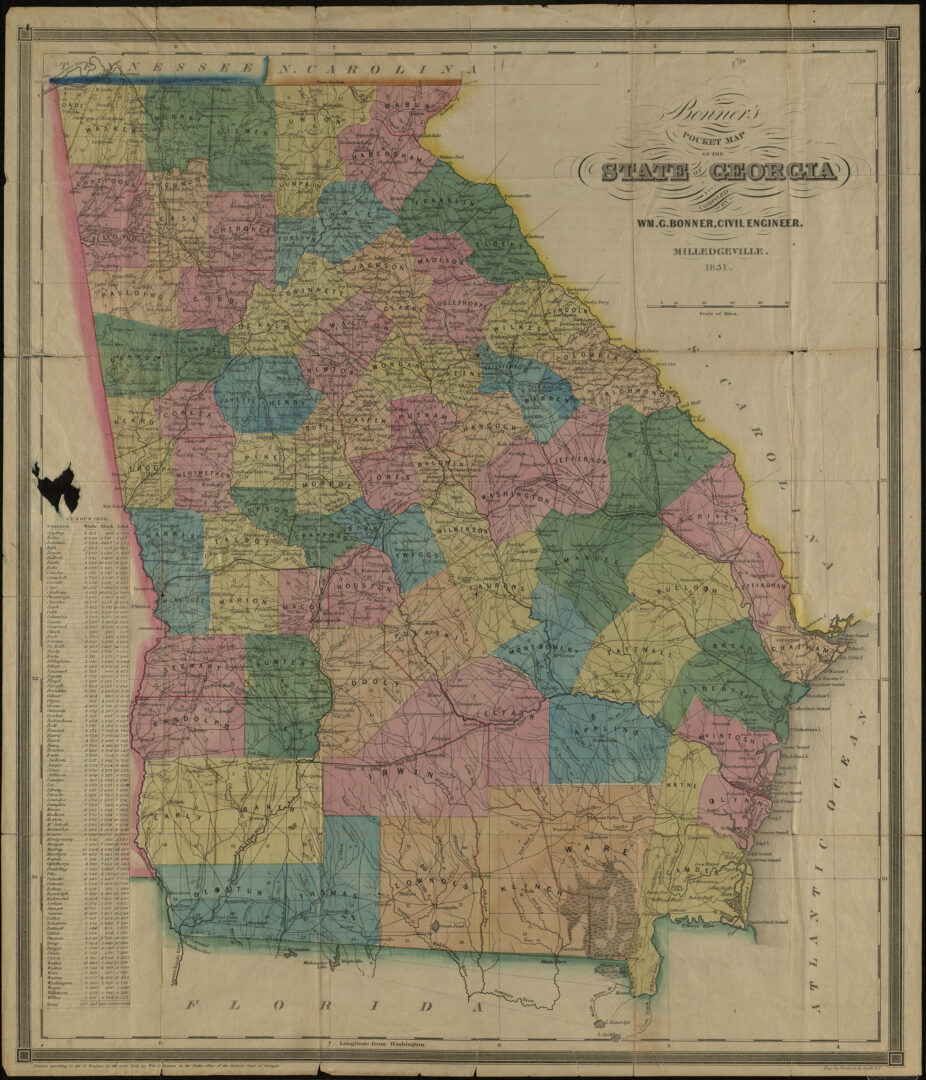

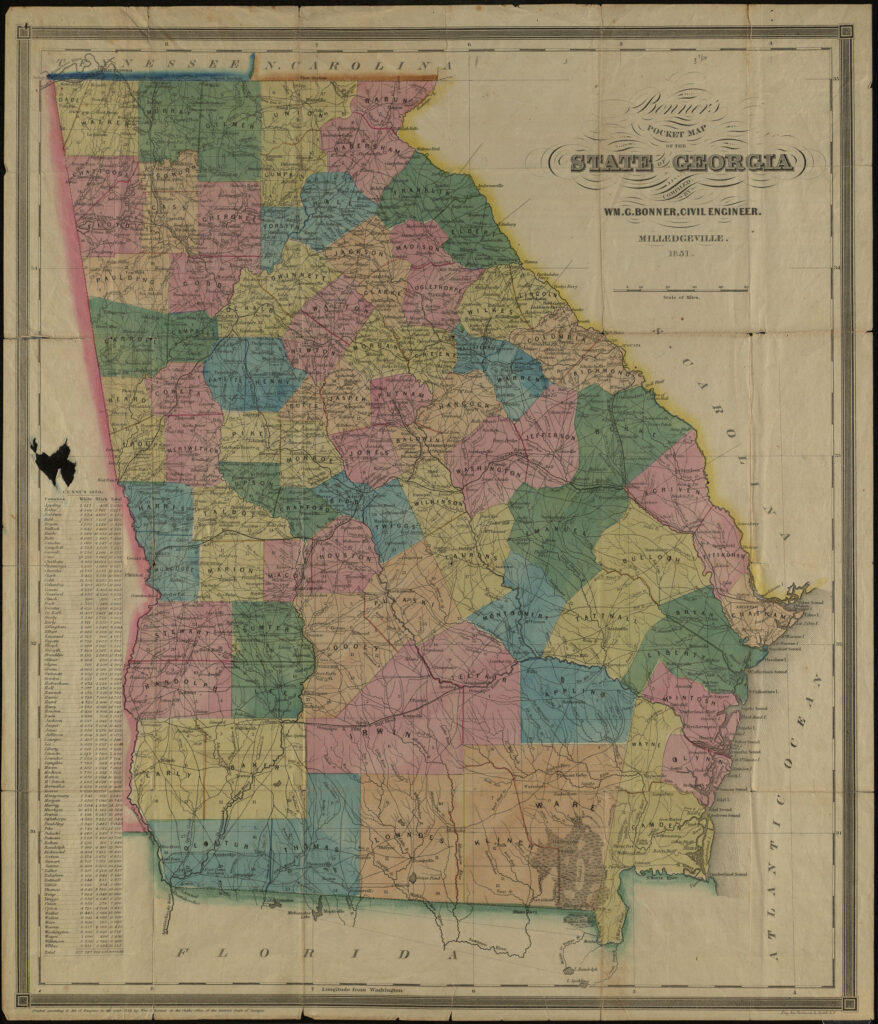

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

After completing his study of the two counties in October 1836, Cotting published Report of a Geological and Agricultural Survey of Burke and Richmond Counties, Georgia. This impressive report came to the attention of Georgia governor William Schley, who urged the state legislature to establish an agricultural and geological survey. The General Assembly responded favorably in December 1836, and Schley appointed Cotting as state geologist in January 1837. By the end of that year Cotting had surveyed ten counties. He encountered problems with the state printer, however, and the report of his research was not published. Because the state was in the throes of a severe financial crisis by then, the General Assembly opted to defer publication until the entire survey was complete.

Cotting conducted the second phase of the survey in 1838, and the third phase in 1839. Those inquiries covered another sixteen counties, but the loss of support from Schley, who had been defeated for reelection, and the state’s continuing fiscal problems caused legislators to lose interest in the project. Although Cotting managed in 1840 to issue a brief preliminary report of the 1839 survey, the General Assembly voted on December 11, 1840, to abolish the office of state geologist. Later that month it approved a resolution allowing Cotting to keep the honorary title of state geologist but authorized no funds to continue his work.

During the next two years, Cotting endeavored to obtain subscriptions so that he could publish reports of his surveys, but the effort was fruitless, despite the strong support of the Milledgeville Federal Union. Unable to elicit sufficient subscriptions, Cotting, with the backing of the same newspaper, sought to salvage a portion of his studies, and in 1843 he published An Essay on the Soils and Available Manures of the State of Georgia. Both Cotting and the Federal Union hoped the small volume would generate income sufficient to continue the research and to publish the complete reports. It did neither, and the results of Cotting’s investigations, excepting the brief preliminary report of the 1839 survey and the essay on the soils of Georgia, came to naught. Eventually, Cotting’s field notes and written reports disappeared, and the fossils and botanical specimens he collected during his surveys were given away or discarded.

Cotting continued for a few years to engage in some geological activities as honorary state geologist, the most notable of which was the donation of several invertebrate fossils to the British geologist Sir Charles Lyell in 1844. During his second visit to the United States, Lyell went to Milledgeville in January 1846 to meet Cotting, who showed him other fossils in the collection, which was housed in the state capitol. Cotting also escorted Lyell around the region to study geological formations. In the meantime, in order to generate income, Cotting returned to teaching. He purchased the Milledgeville Female Academy in August 1842 and operated it with his wife for several years.

Highly respected in the Milledgeville community, Cotting died on October 13, 1867. The General Assembly reestablished the office of state geologist in 1889, and many important studies of the state’s natural resources have ensued over the years—all, however, without any direct benefit from Cotting’s pioneering work.