The Georgia Salzburgers, a group of German-speaking Protestant colonists, founded the town of Ebenezer in what is now Effingham County. Arriving in 1734, the group received support from King George II of England and the Georgia Trustees after they were expelled from their home in the Catholic principality of Salzburg (in present-day Austria). The Salzburgers survived extreme hardships in both Europe and Georgia to establish a prosperous and culturally unique community.

Protestant Expulsion

In 1731 Count Leopold von Firmian, the Catholic archbishop and prince of independent Salzburg, issued the Edict of Expulsion, forcing twenty thousand Protestants from their homes. He gave propertied subjects three months to dispose of their holdings and leave the country; non-propertied persons had but eight days to leave. A majority of these outcasts settled in East Prussia and Holland.

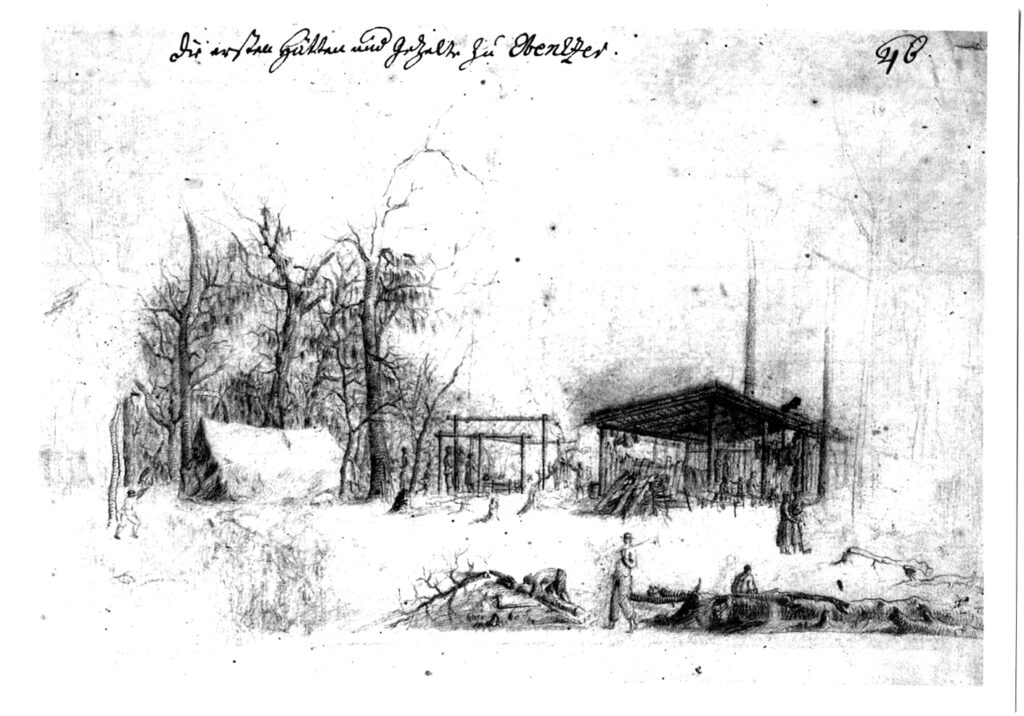

Illustration by Philip Georg Friedrich von Reck

Pastor Samuel Urlsperger of Augsburg (in present-day Germany) and his organization, the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, identified with the plight of the Salzburgers and asked King George II of England for help. George, a German duke and a Lutheran, sympathized with the Salzburgers and offered them a place in his Georgia colony. About 300 Salzburgers, under the leadership of pastors Johann Martin Boltzius and Israel Gronau, accepted the invitation.

The first group of Salzburgers sailed from England to Georgia in 1734, arriving in Charleston, South Carolina, on March 7, then proceeding to Savannah on March 12. They were met by James Oglethorpe, the founder of the Georgia colony, who assigned them a home about twenty-five miles upriver in a low-lying area on Ebenezer Creek. Subsequent ships brought the rest of the original exiled Salzburgers, as well as other European settlers from German-speaking nations who also became identified generically as Salzburgers.

Early Life in Georgia

Upon arrival, Boltzius established the Jerusalem Church (later Jerusalem Evangelical Lutheran Church) and administered the settlement of Ebenezer with a strong religious element. Because of their harrowing experience in Europe and their level of religious devotion, the Salzburgers secured the admiration and financial support of English authorities, who idealized them as model colonists. Indeed, the qualities of piety, modesty, and industriousness were rooted in the Salzburgers’ spiritual traditions, which emphasized personal conviction and community activities. Their fierce sense of independence, however, as well as a mistrust of secular authority isolated the Salzburgers from the rest of the Georgia colony.

Photograph by Bruce Tuten

The original settlement of Ebenezer failed largely because of its poor location. It was too far inland, and no clear waterway existed to the Savannah River. An eight-mile journey on foot had to be made on an oft-flooded road to the Scottish settlement of Abercorn to procure provisions and supplies. Additionally, about thirty settlers died of dysentery in the damp conditions during the first two years of the settlement. Crops and livestock could not be sustained in the swamp. The Salzburgers’ healthy alliance with the Trustees, especially on the issue of prohibiting slavery, assured them of further aid, however.

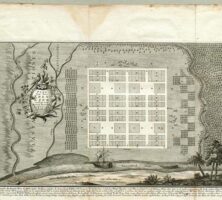

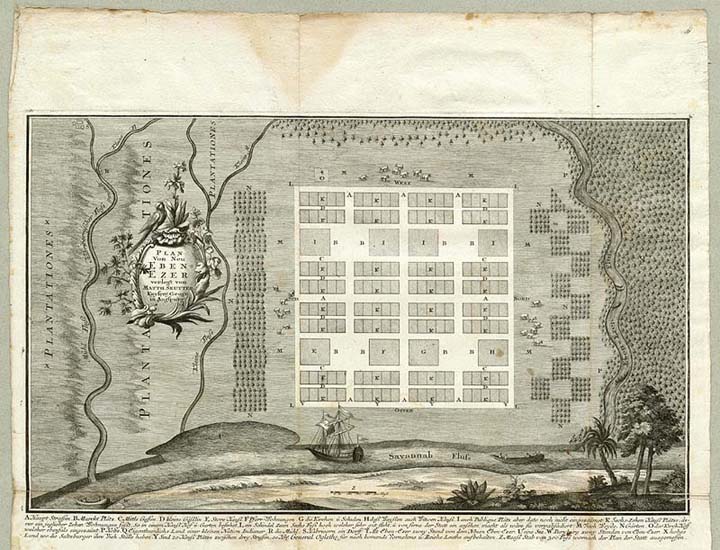

Prosperity and Decline at New Ebenezer

In early 1736 Oglethorpe gave the Salzburgers a new site on the high bluffs above the Savannah River. The settlers referred to the new settlement as New Ebenezer. By the fall of 1737 many farmsteads had been established on the bluff. In 1740 the Salzburgers, with funding from the Trustees, built the first water-driven gristmill in the Georgia colony, and they built a second in 1751. Stamping mills for rice and barley stood beside two sawmills, as Ebenezer’s lumber became a valuable commodity for the Georgia colony. Widows and orphans operated the first silk filature (a facility for reeling silk from cocoons) in Georgia. The Salzburgers also established the first Sunday school in Georgia in 1734 and the first orphanage in 1737.

Print from Von Reck Archive, Royal Library of Denmark, Copenhagen

By 1752 the Salzburgers had expanded north of Ebenezer Creek to establish the Bethany settlement, as well as three other minor settlements. Jerusalem Church thrived with a new red-brick edifice, which was completed in 1769. The increasingly multicultural community grew to around 1,200 people and covered about twenty-five square miles before the American Revolution (1775-83). Expansion came with a price, however, as the once-thriving traditions and solidarity of the Salzburgers began to fade. After the death of Boltzius in 1765, the community lacked a clear leader and further lost its cohesion.

The Revolutionary War brought destruction and desertion to the area. British troops set up headquarters at Ebenezer, and soldiers plundered many houses and targeted them for cannon practice. They used the church as a hospital, and its pews as firewood. Though American troops retook Ebenezer in 1782, naming it the capital of Georgia for two weeks, most Salzburgers deserted the area, seeking employment and fertile land in other locations.

Salzburger Tradition Today

Jerusalem Church survived not only the revolution but also occupation by Union general William T. Sherman’s troops during the Civil War (1861-65), as well as an 1886 earthquake. The church, which still stands, houses the oldest continuing Lutheran congregation in the United States to worship in its original building. A replica of the orphanage serves as a museum, and several monuments celebrating the Salzburgers have been erected in Effingham County and Savannah.

Many descendants of the Salzburgers still live in Effingham and Chatham counties, and a number of them are active in the Georgia Salzburger Society, an independently operating genealogical and archaeological organization founded in 1925.