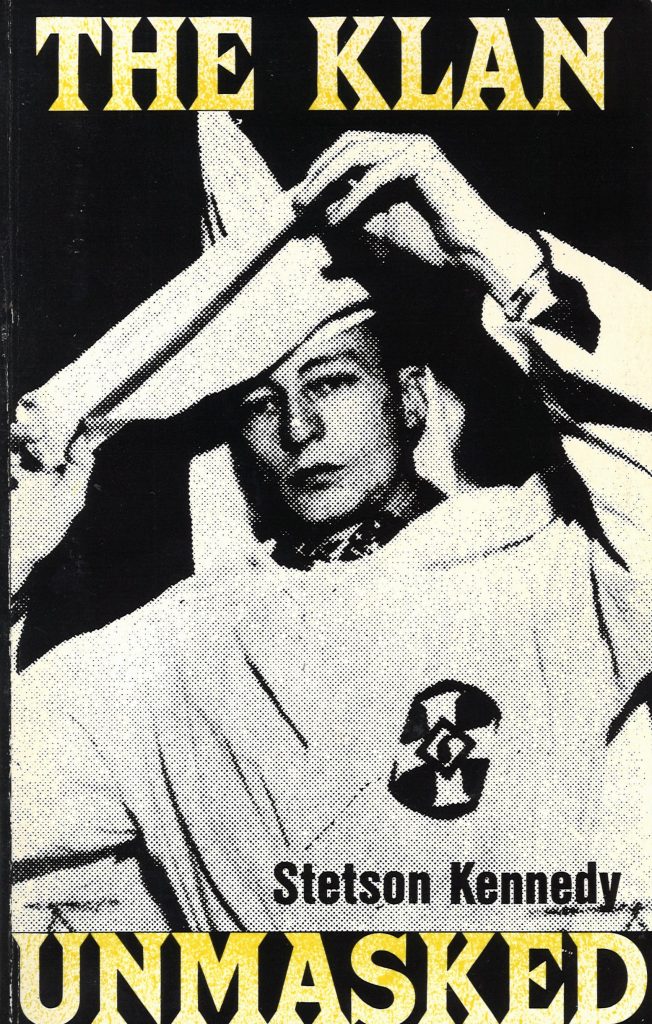

Folklorist, investigative reporter, author, and labor activist Stetson Kennedy occupies a unique position in Georgia’s literary history. In the 1940s Kennedy infiltrated an Atlanta chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, an experience he recounted in two books, The Klan Unmasked and Southern Exposure. During his time undercover, he worked with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and the Anti-Defamation League. Kennedy’s writing, as well as his work as an undercover agent, helped shed light on the Klan’s “Invisible Empire,” exposing the organization’s penchant for extralegal violence and contributing to its decline in the 1950s and 1960s.

William Stetson Kennedy was born in Jacksonville, Florida, on October 5, 1916, to Willye Stetson and George Wallace Kennedy. His father was from Statesboro, and his mother’s family was from Macon and Milledgeville. The Stetson Sanford House in Milledgeville, which serves as headquarters for the Old Capital Museum Society, is a family home on his mother’s side. Kennedy became enamored with Floridian folkways at an early age, and wrote poetry about Florida nature during his youth. He was educated in Jacksonville’s public schools and in 1935 enrolled briefly at the University of Florida.

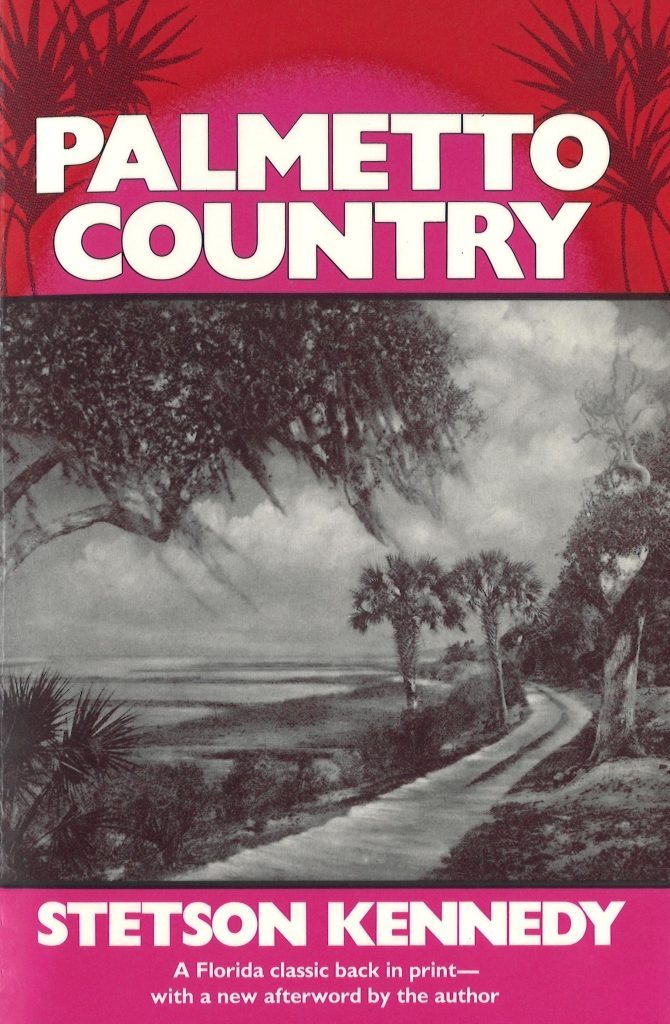

In 1937 Kennedy joined the Federal Writers Project in Florida and spent the next five years collecting oral histories alongside fiction writer Zora Neale Hurston and folklorist Alan Lomax, among others. Kennedy had a large hand in editing several volumes generated by the Florida project, including The WPA Guide to Florida, A Guide to Key West, and The Florida Negro. A great deal of unused material from these projects was collected in Kennedy’s Palmetto Country (1942), a book commissioned by Georgia writer Erskine Caldwell for his American Folkways Series. Embracing as it does southern Georgia and Alabama as well as Florida, Palmetto Country was celebrated on its fiftieth anniversary by a gathering of the historical societies of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida in St. Augustine, Florida, on Kennedy’s eighty-fifth birthday. The book was brought back into print by the Florida Historical Society in 2009.

The Florida project ended when the United States entered World War II (1941-45). In 1942 Kennedy accepted a position as southeastern editorial director of the Congress of Industrial Organization’s political action committee in Atlanta. In this capacity he authored a series of monographs dealing with the poll tax, white primary, and other restrictions on voting that delimited democracy not only in Georgia but throughout the South. Because a bad back prevented him from serving overseas during the war, Kennedy resolved to perform his patriotic duties in Georgia, infiltrating both the Klan and the Columbians, an Atlanta-based neo-Nazi organization.

Posing as an encyclopedia salesman and adopting the alias John S. Perkins, Kennedy ingratiated himself into the Klan’s company in 1946, donning a hood and joining the order in a ritualistic nighttime initiation atop Stone Mountain. As soon as he learned the group’s secrets, Kennedy shared them with interested parties—journalists, law enforcement officials, and even the producers of the popular radio program The Adventures of Superman, who worked the secrets into the show’s script and broadcast them before a national audience. Kennedy also provided national radio journalist Drew Pearson with Klan signs and countersigns, which Pearson described each week on his Washington Merry-Go-Round radio program.

After spending more than a year undercover with both organizations, Kennedy agreed to testify at the 1947 trial of Homer Loomis and Emory Burke, the leaders of the Columbians. While Kennedy’s testimony helped to secure guilty verdicts for both men, his appearance also exposed his double life, bringing to an end his days as an undercover “Klan buster.”

Kennedy left the country in 1952 and traveled widely thereafter. He wrote about his experiences during his travels but was unable to find a publisher for his manuscript until 1954, when Arco, in London, England, agreed to publish the narrative. Originally entitled I Rode with the Ku Klux Klan, the book was subsequently published in the United States as Passage to Violence (with the first thirty pages of the original version omitted) but not widely circulated, and the work received significant attention only in 1990, upon its reissue as The Klan Unmasked. Around 1954 Kennedy met the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre while living in Paris, France, and Sartre published two articles by Kennedy in his journal Les Temps Modernes. In 1955 Sartre published under his own imprint Kennedy’s book The Jim Crow Guide to the USA, long before the work found an American publisher.

After spending nearly a decade abroad, Kennedy returned to the United States in 1960 and worked briefly as a southeastern correspondent for the Pittsburgh (PA) Courier, a leading African American newspaper. He covered the events of the civil rights movement for the Courier, including the Albany Movement in Georgia. He also wrote the weekly column “Up Front Down South” under the pseudonym “Daddy Mention,” a Black folk hero. In his column Kennedy urged Black leaders to support the efforts of Martin Luther King Jr.

Kennedy spent the rest of his professional life under the employ of various community development agencies in the Jacksonville area.

In 2006, after praising Kennedy’s courage in their best-selling book Freakonomics, authors Stephen J. Dubner and Steven D. Levitt published an article in the New York Times Magazine questioning the accuracy of his accounts. According to Dubner and Levitt, a number of the events described in The Klan Unmasked were embellished or based on secondhand information, and they accused Kennedy of failing to properly acknowledge the contributions of other undercover agents.

In his response Kennedy acknowledged that the charges held some truth, but added that he had admitted as much about twenty years earlier to Peggy Bulger, then a doctoral student researching Kennedy’s life story. Though he expressed regret at not having fully elaborated upon the book’s nature when it was reissued in 1990, Kennedy nonetheless defended his decisions as having been necessary to conceal the identities of his accomplices and ensure the book’s publication. He moreover provided reams of documents verifying his undercover work, including interviews given by a number of former state officials. “Stetson didn’t do it all,” said former assistant attorney general of Georgia Daniel Duke in one interview, “but he did plenty.”

In 2003 the Stetson Kennedy Foundation, headquartered in Florida at Beluthahatchee Park (St. Johns County), was formed with the mission of championing human rights, traditional cultures, and environmental stewardship.

Kennedy’s papers are housed in the archives at various institutions around the country, including the University of Florida, Georgia State University, and the New York Public Library. His numerous awards and honors include election as a fellow of the Society of Professional Journalists and induction into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame.

Kennedy died on August 27, 2011, near St. Augustine.