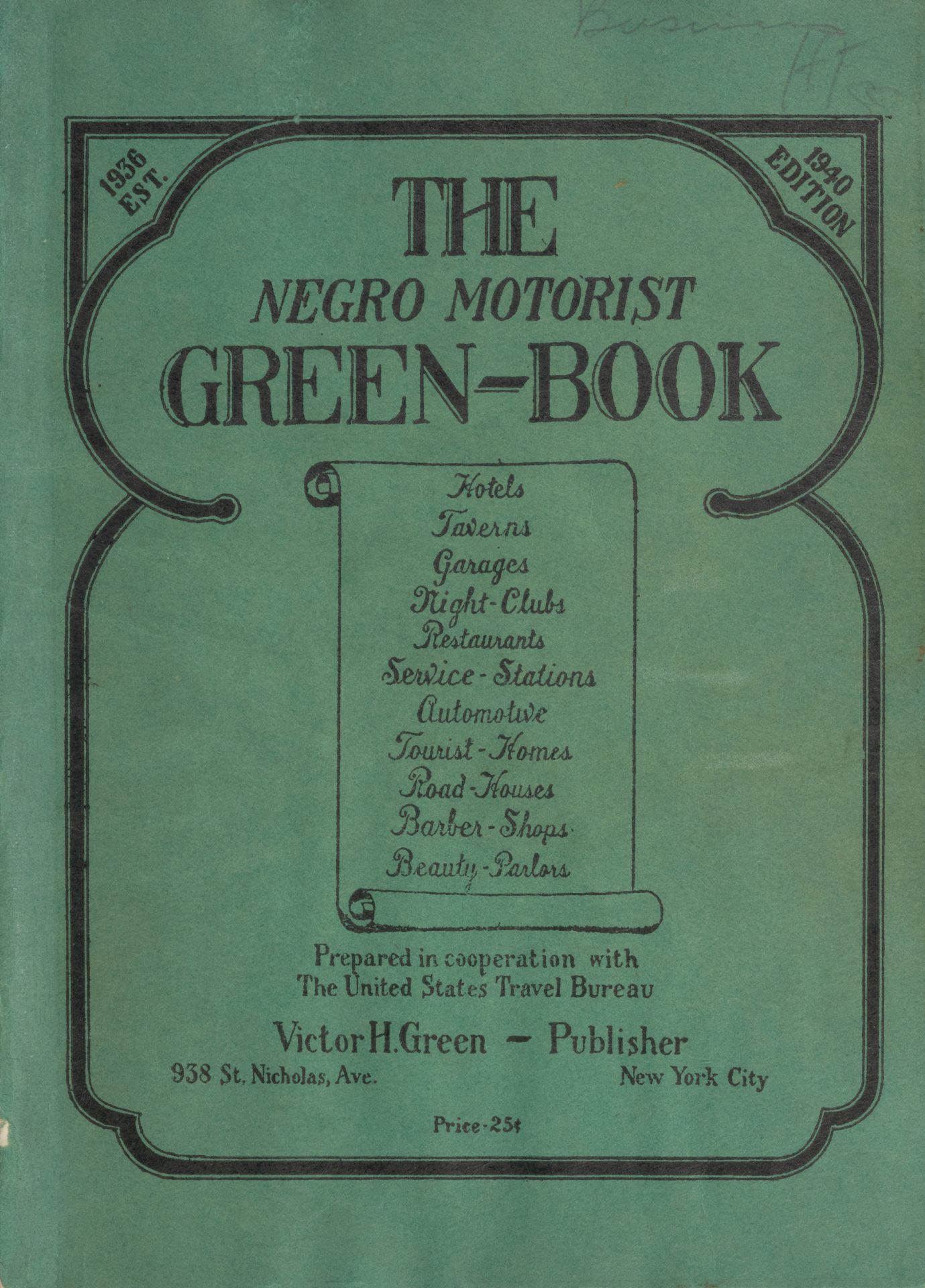

Sundown towns are all-white communities that intentionally exclude African Americans or other minorities from residing within their boundaries by forced expulsion, violent threats, or economic coercion. Multiple sundown towns and counties appeared in Georgia during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Creation and Enforcement

Most sundown towns emerged between the 1880s and 1960s. They were common in communities of the Northeast, Midwest, West, and parts of the South that had few African American and other minority residents prior to the 1880s. In southern counties dominated by plantation agriculture, white residents focused on subjugating Black workers rather than expelling them. As a result, Georgia’s sundown towns usually appeared in regions outside the Black Belt, such as the Appalachian Mountains or the suburbs of rapidly growing cities.

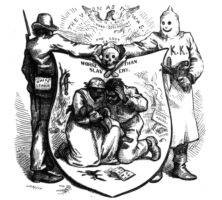

Most sundown towns were the product of violence. In some instances, white mobs perpetrated racial cleansings that expelled entire Black communities in a single day. In other cases, white gangs utilized systematic threats of violence punctuated by lynchings or public acts of racial terror. In many cases, whites resorted to “whitecapping” or “night riding,” acts of organized, extralegal violence executed under the cover of night, that sought to terrorize Black families and communities. Public lynchings and night riding drove Black residents from Forsyth and Dawson counties in 1912, for example.

Whites also used legal means to displace Black residents. Anti-Black housing ordinances and zoning laws were particularly common, especially in suburban communities, and “buyout” campaigns forced Black residents to sell their homes, while landlords refused to renew existing leases. In Chamblee, local officials simply refused to fund Black schools prior to the desegregation of public education, creating a powerful disincentive to Black settlement. Other common methods of exclusion included social ostracization and the selective enforcement of criminal codes. But white violence—or the threat thereof—remained the primary method of enforcement, and communities sometimes even posted signage at the city limits to discourage Black visitors from remaining after nightfall.

Sundown Towns in Georgia

Sociologist James Loewen used oral histories, census data, and other historical records to identify sundown towns nationwide. His research identified seven communities in Georgia that were known or likely to have been sundown towns, while identifying twelve others that shared similar characteristics.

Blue Ridge had virtually no Black residents for decades, and oral evidence suggests that African Americans may not have been allowed in the city limits after dark. As of the 2020 census, the community had fewer than twenty Black residents.

Chamblee had only two Black residents in 1960 and one in 1970. Today it is a racially diverse suburb.

Thomas County voted to expel its Jewish residents in 1862 after blaming them for the collapse of the local wartime economy. It is unclear when this prohibition ended, but a Jewish congregation had been established in the county seat of Thomasville by 1885.

Union County had only one Black resident listed in the 1950 and 1960 censuses. By 2020, more than 200 African Americans resided in the county.

Dawson County expelled more than 100 African Americans in 1912. Census data indicates that there were no Black residents in 1920 and 1950; only in 2010 did the Black population surpass that of the 1910 census.

Towns County saw a sharp drop in Black residents between 1900 and 1910 and had zero African Americans within its borders from 1920 to 1940. Oral evidence suggests the county seat of Hiawassee had a reputation for violence against African Americans, particularly after nightfall. Black residents did not account for even one percent of the county’s residents until the 2020 census, which counted 158 Black residents out of a total population of 12,493.

Forsyth County

In 1912 white residents violently expelled all 1,098 Black residents from Forsyth County. In the years that followed, white Forsythians often employed violence or intimidation to discourage Black visitors and residents, reinforcing the county’s reputation as Georgia’s most notorious sundown community. In 1915, for example, a driving tour of prominent Georgians and news reporters stopped in Cumming, the county seat. Noticing their Black chauffeurs, locals pelted the cars with rocks and attempted to drag a Black man out of his vehicle until one of the wealthy passengers drew a revolver. In 1968 a gang of white men surrounded a group of ten Black schoolchildren on a Forsyth County campground, threatening them and chanting slurs until they left. In 1980 two white residents shot a Black firefighter, Miguel Marcelli, in the head shortly after sundown.

Forsyth County gained a national reputation as a sundown town in 1987, following news coverage of attacks against civil rights marchers after a Ku Klux Klan (KKK) rally in the county. With white residents violently enforcing the racial prohibition for decades, no census recorded more than 50 African Americans (out of a total population of more than 10,000) until 2000. Though Forsyth County experienced significant growth in the early twenty-first century, African Americans still comprise a smaller proportion of the county’s population than in 1910.