Tabby is a type of building material used in the coastal Southeast from the late 1500s to the 1850s. Historians disagree on whether its use originated along the northwest African coast and was taken to Spain and Portugal, or vice versa.

The origin of the word tabby itself is unclear: the Spanish word tapia means a mud wall, and the Arabic word tabbi means a mixture of mortar and lime. Similar words also appear in both Portuguese and Gullah. The Spanish brought the concept of tabby to the New World and used it extensively in Florida. Locals in Georgia adapted the concept or “recipe” for tabby to local materials.

True tabby is made of equal parts lime, water, sand, oyster shells, and ash. The ash is a byproduct of preparing the lime, but its presence contributes to the hardening of the end product. Tabby can be poured into molds for foundations, walls, floors, roofs, columns, and other structural elements. It dries to a hard finish, is generally a grayish-white color with variations according to the materials used, and is extremely durable. It is best maintained by applying stucco to the outer surfaces as protection from water damage. Roots and vines can cause the deterioration of tabby, so vegetation must be kept away from structures built of the material.

In 1702 the British lay siege to Spanish-held St. Augustine, Florida, where tabby had been in use for over a century. Soon afterward, tabby structures began appearing in the British colony of South Carolina. James Oglethorpe, who had seen tabby military structures near Port Royal, South Carolina, is credited with its initial use in Georgia. As settlements spread along the Georgia coast, the need for military protection also grew. Tabby was regarded as the logical building material for fortifications. In 1736 Oglethorpe began advocating its use on St. Simons Island, which contained acres of Indian middens, or piles of oyster shells. He even built himself a tabby house near Fort Frederica. With the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, the threat of Spanish invasion ceased, and the use of “Oglethorpe tabby” diminished.

James Spalding purchased Oglethorpe’s house in 1771. His son Thomas was born there in 1774 and became a leading agriculturist and political figure of his day. Thomas Spalding’s advocacy of tabby on his Sapelo Island plantation led to a tabby revival that lasted into the 1840s; tabby from this period is sometimes called “Spalding tabby.” The end of slavery; the depletion of materials, especially the middens; and the introduction from England of Portland cement (made by burning limestone and clay) by 1870 led to another decline in the use of tabby.

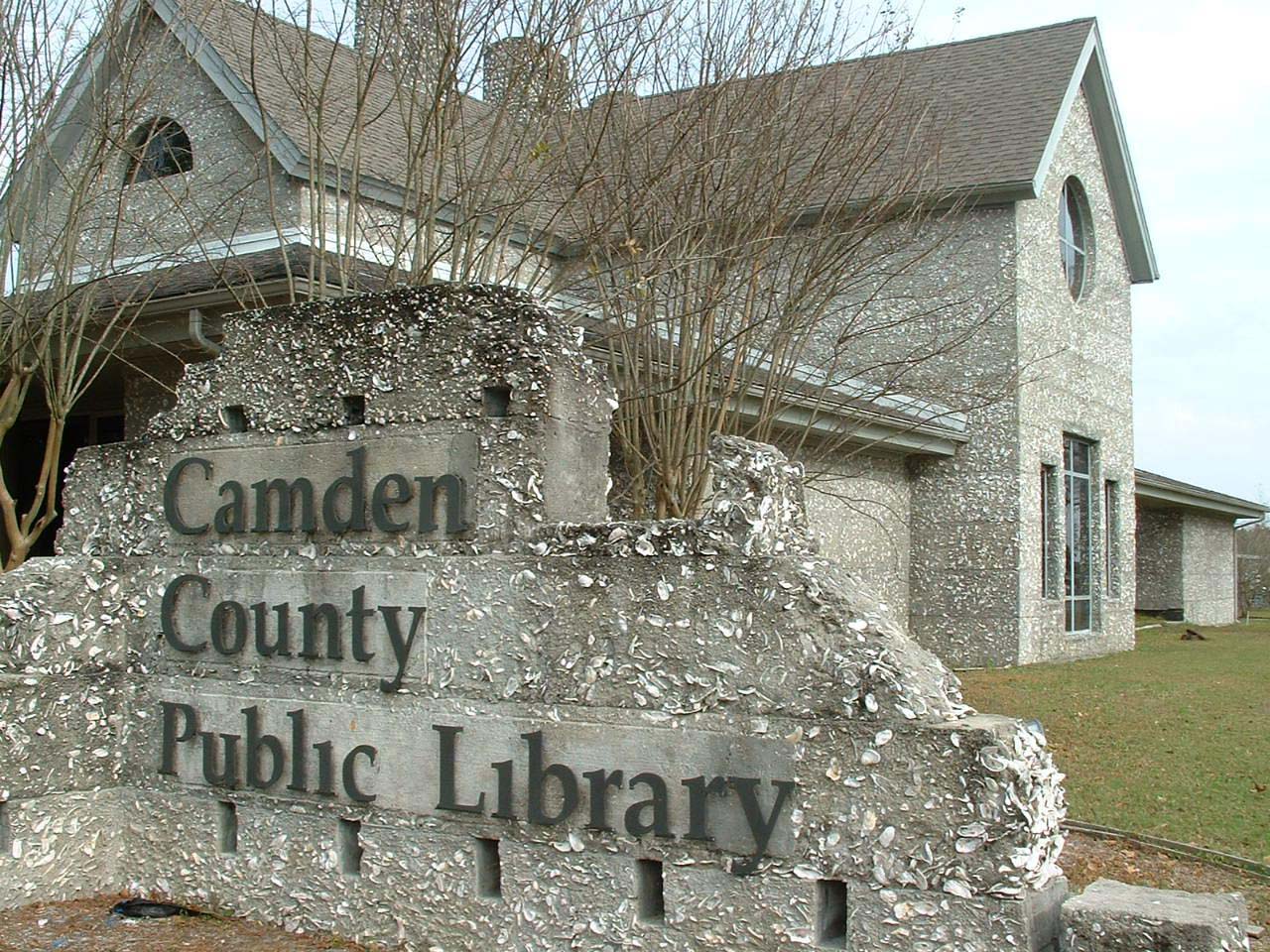

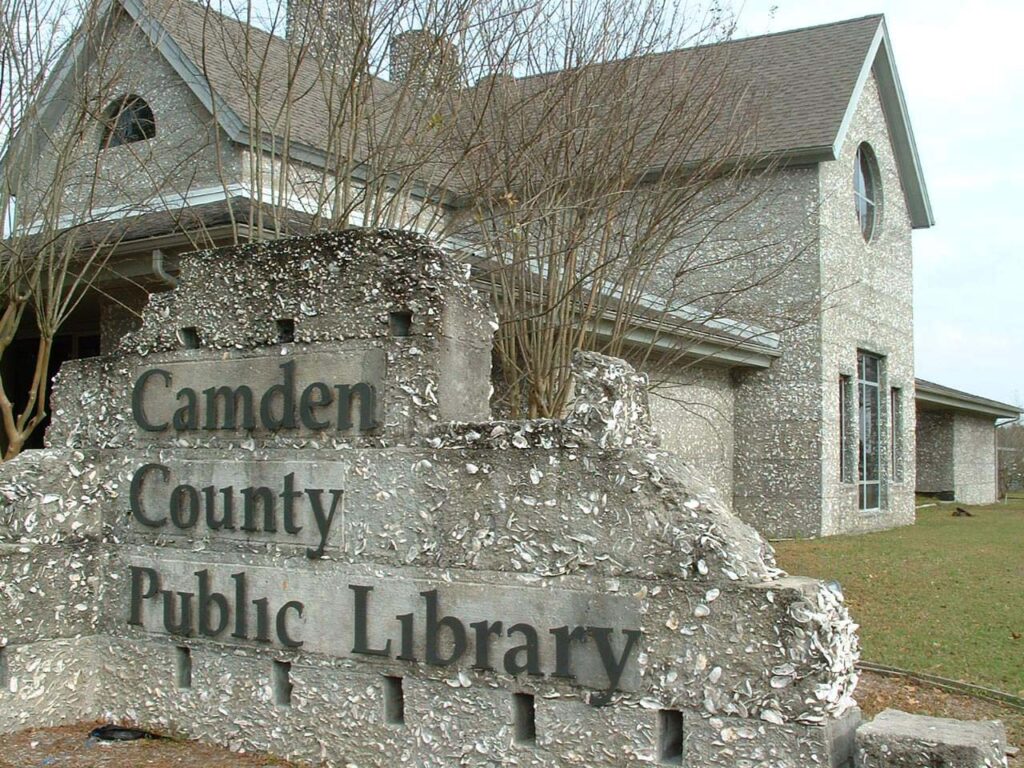

When Jekyll Island was developed as a millionaire’s retreat in the 1880s, another tabby revival occurred, and several mansions on the island were built of tabby mixed with Portland cement. Although the use of traditional tabby virtually disappeared after 1925, tabby construction is not totally extinct in Georgia. As late as 1988 the public library in Camden County, near Woodbine, was built with “revival tabby.” Most new buildings that appear to be constructed with tabby are really made of “pseudo-tabby,” or Portland cement with shell applied to the surface.

Among the existing examples of true tabby structures in Georgia today are the Wormsloe Plantation outside Savannah, the Horton-DuBignon House on Jekyll Island, and the ruins of Spalding’s plantation on Sapelo Island.