The first twenty years of Georgia history are referred to as Trustee Georgia because during that time a Board of Trustees governed the colony. England’s King George signed a charter establishing the colony and creating its governing board on April 21, 1732.

Origins

James Edward Oglethorpe, famous for conducting a parliamentary investigation into the conditions of London prisons, exercised a leading role in the movement to found the new colony. He confided to his friend John Lord Viscount Percival (known as the first earl of Egmont after that title was conferred on him in 1733) that he intended to help released debtors begin a new life in America. In fact, Oglethorpe had received a grant of £5,000 to carry out his plan. In 1729 Dr. Thomas Bray chose trustees to administer his estate. In addition to Oglethorpe, the trustees, called the Associates of Dr. Bray, included several future members of the Georgia Trust, notably Percival, James Vernon, and Thomas Coram. Coram is better known as the founder of the Foundling Hospital in London. Oglethorpe and his friends decided to add the Bray legacy to the funds in hand for the purpose of establishing a new colony between the Savannah and Altamaha rivers, in territory claimed by both the province of South Carolina and the Spanish colony of Florida.

On September 17, 1730, the associates presented a petition for a charter to the Privy Council, Parliament’s executive body, headed by the chancellor of the exchequer, Robert Walpole. The petition was routinely passed on to the notoriously inefficient Board of Trade, which dawdled for a year without acting. Walpole, the prime minister, was less than eager to challenge the Spanish, who had a prior claim to the region requested by the petitioners. Walpole needed the support of the influential members of Parliament who supported the charter, however, and he managed to bring the charter before the Privy Council. After going through several revisions, the notion of helping debtors gave way to a more pragmatic plan to send over “the deserving poor” who would protect South Carolina while producing such goods as wine and silk for England.

The Georgia Charter

The charter contained contradictions. The colonists were entitled to all the rights of Englishmen, yet there was no provision for the essential right of local government. Religious liberty was guaranteed, except for Roman Catholicism and Judaism. A group of Jews landed in Georgia without explicit permission in 1733 but were allowed to remain. The charter created a corporate body called a Trust and provided for an unspecified number of Trustees who would govern the colony from England. Seventy-one men served as Trustees during the life of the Trust. Trustees were forbidden by the charter from holding office or land in Georgia, nor were they paid. Presumably, their motives for serving were humanitarian, and their motto was Non sibi sed aliis (“Not for self, but for others”). The charter provided that the body of Trustees elect fifteen members to serve as an executive committee called the Common Council, and specified a quorum of eight to transact business. As time went on, the council frequently lacked a quorum; those present would then assume the status of the whole body of Trustees, a pragmatic solution not envisioned by the framers of the charter. Historian John McCain counted 215 meetings of the Common Council and 512 meetings of the corporation.

Twelve Trustees attended the first meeting on July 20, 1732, at the Georgia office in the Old Palace Yard, conveniently close to Westminster. Committees were named to solicit contributions and interview applicants to the new colony. On November 17, 1732, seven Trustees bade farewell to Oglethorpe and the first settlers as they left from Gravesend aboard the Anne. The Trustees succeeded in obtaining £10,000 from the government in 1733 and lesser amounts in subsequent years. Georgia was the only American colony that depended on Parliament’s annual subsidies.

Active Trustees

The most active members of the Trust, in terms of their attendance at council, corporation, or committee meetings, were, in order of frequency, James Vernon, Percival (the first earl of Egmont), Henry L’Apostre, Samuel Smith, Thomas Tower, John Laroche, Robert Hucks, Stephen Hales, James Oglethorpe, and Anthony Ashley Cooper, fourth earl of Shaftesbury. The number of meetings attended ranged from Vernon’s 712 to Shaftesbury’s 266. Sixty-one Trustees attended fewer meetings.

James Vernon, one of the original Associates of Dr. Bray and an architect of the charter, maintained an interest in Georgia throughout the life of the Trust. He arranged the Salzburger settlement and negotiated with the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts for missionaries. He differed from Egmont and Oglethorpe in his willingness to respond to the colonists’ complaints. When Oglethorpe became preoccupied with the Spanish war, Vernon proposed the plan of dividing the colony into two provinces, Savannah and Frederica, each with a president and magistrates. The Trustees named William Stephens president in Savannah, and he served until 1751, when he was replaced by Henry Parker in the final year of the Trust’s tenure. Oglethorpe neglected to name a president for Frederica, and the magistrates there were instructed to report to Stephens. The Trustees did not want to appoint a single governor because the king in council had to approve the appointment of governors, and the Trustees preferred to keep control in their hands. After Egmont’s retirement in 1742, Vernon became the indispensable man. He missed only 4 of 114 meetings during the last nine years of the Trust and supervised the removal of restrictions on land tenure, rum, and slavery.

Egmont, the first president of the Common Council and the dominant figure among the Trustees until his retirement, acted as Georgia’s champion in Parliament. He strongly opposed Walpole’s attempts to conciliate Spain at the expense of Georgia. He had to walk a careful line, however, because the Trustees depended upon Walpole for their annual subsidies.

Other Trustees contributed according to their abilities. Henry L’Apostre advised on finances, Samuel Smith on religion, and Thomas Tower on legal matters, particularly on instructions to Georgia officials. Stephen Hales’s closeness to the royal family and his standing as a scientist lent prestige to the body of Trustees. Shaftesbury, a political opponent of Walpole, joined the Common Council in 1733 and, except for a brief resignation, remained faithful to the end. He led the negotiations to convert Georgia to a royal colony. For the entire twenty years the Trustees employed only two staff members, Benjamin Martyn as secretary and Harman Verelst as accountant.

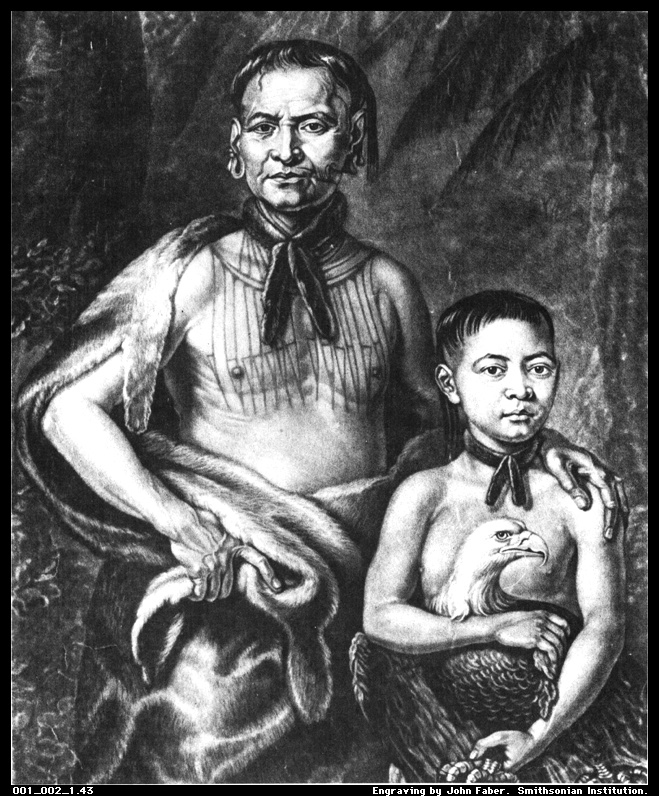

Georgia Indians in London

Oglethorpe returned to England in June 1734 with goodwill ambassadors in the persons of Yamacraw chief Tomochichi, Senauki, his wife, their nephew Toonahowi, and six other Lower Creek tribesmen. The Indians were regarded as celebrities, feted by the Trustees, interviewed by the king and queen, entertained by the archbishop of Canterbury at Lambeth Palace, and made available to meet the public. All but two of them posed with a large number of Trustees at the Georgia office for the painter William Verelst. One of the absent Indians died of smallpox, despite the ministrations of the eminent physician Sir Hans Sloane, and was buried by his grieving comrades in the burial plot of St. John’s in Westminster. After performing their social obligations, the Indians became tourists, visiting the Tower of London, St. Paul’s Cathedral, Oglethorpe’s Westbrook Manor, and Egmont’s Charlton House, and enjoying a variety of plays, from Shakespearean dramas to comic farces.

Salzburgers, Moravians, and Highlanders

The Indians departed on October 31, 1734. With them went fifty-seven Salzburgers to join the forty-two families already in Georgia at Ebenezer. In 1734 and 1735 two groups of Moravians went to Georgia. As pacifists they opposed doing military duty and left Georgia by 1740. After delivering the Indians and Salzburgers to Georgia, Captain George Dunbar took his ship, the Prince of Wales, to Scotland. Dunbar and Hugh Mackay recruited 177 Highlanders, most of them members of Clan Chattan in Inverness-shire. In 1736 the Highlanders founded Darien on Georgia’s southern boundary, the Altamaha River. The Scots of Darien, who were extremely capable fighters, assisted Oglethorpe during the siege of St Augustine in 1740. They were also responsible for introducing another denomination of Christianity to the colony, Presbyterianism. Dunbar subsequently served as Oglethorpe’s aide in Georgia and in Oglethorpe’s campaign against the Scots in 1745.

Oglethorpe went to Georgia in 1736, with the approval of his fellow Trustees, to found two new settlements on the frontiers, Frederica on St. Simons Island and Augusta at the headwaters of the Savannah River in Indian country. Both places were garrisoned by troops. In 1737 Oglethorpe returned to England to demand a regiment of regulars from a reluctant Walpole. Not only did he get his regiment and a commission as colonel, but Egmont persuaded Walpole to pay for all military expenses.

Trustee Legislation and Reactions

In 1735 the Trustees proposed three pieces of legislation to the Privy Council and had the satisfaction of securing the concurrence of king and council. An Indian act required Georgia licenses for trading west of the Savannah River. Another act banned the use of rum in Georgia. A third act outlawed slavery in Georgia. South Carolina protested the Indian act vehemently and objected to the Trustees’ order to restrict the passage of rum on the Savannah River. The Board of Trade sided with South Carolina, and a compromise was reached, allowing traders with Carolina licenses to continue their traditional trade west of the Savannah River. The Trustees objected to the Board of Trade’s tampering and refrained from proposing any additional legislation requiring approval of the Privy Council.

Continual complaints by the colonists and the near abandonment of Georgia during the war with Spain discouraged all but the most dedicated of the Trustees. Especially embarrassing was the list of grievances presented on the floor of Parliament by Thomas Stephens, son of the Trustees’ agent in Georgia, William Stephens. A committee went through the motions of looking into the complaints and then exonerated the Trustees. Stephens was made to kneel in apology on the floor of Parliament. However, the prestige of the Trustees had been wounded, and their influence in Parliament weakened. Walpole lost office in 1742, and the new administration declined the Trustees’ request for funding. Egmont resigned in protest, but not all the Trustees gave up. Under the leadership of Vernon and Shaftesbury, the Trustees conciliated the administration, and the government renewed the annual subsidies until 1751, when the Trustees’ request was again denied.

Oglethorpe returned from Georgia in 1743 and never again showed the same enthusiasm for the work of the Trust. He disagreed with the relaxation of the ban on rum in 1742 and with the admission of slavery in 1751. He engaged in an unfortunate argument with the Trustees over expenses. The accountant claimed that he owed the Trust £1,412 of funds used for military purposes for which he had been compensated. Oglethorpe countered that the Trustees owed him far more than that amount. No agreement was reached. Oglethorpe attended his last meeting on March 16, 1749.

End of Trustee Rule

In March 1750 the Trustees called upon Georgians to elect delegates to the first representative assembly but cautioned them only to advise the Trustees, not to legislate. Augusta and Ebenezer each had two delegates, Savannah had four, and every other town and village had one. Frederica, now practically abandoned, sent no delegate. Sixteen representatives met in Savannah on January 14, 1751, and elected Francis Harris speaker. Most of the resolutions concerned improving trade. The delegates showed maturity in requesting the right to enact local legislation, and they opposed any annexation effort on the part of South Carolina. The Trustees intended to permit further assemblies, but the failure of Parliament to vote a subsidy in 1751 caused the Trustees to enter into negotiations to turn the colony over to the government a year before the charter expired. Only four members of the Trust attended the last meeting on June 23, 1752, and of the original Trustees only James Vernon persevered to the end.

The earl of Halifax, the new president of the Board of Trade, secured broader powers and infused new life int the administration of the board. He regretted that the colonies had been neglected for so long, and he intended to make Georgia a model colony and an example to others. Thus Georgia passed from the control of one set of gentlemen of Parliament to another.

In conjunction with the governor’s office, in 2008 the Georgia Historical Society created an awards program called the Georgia Trustees as a way of recognizing Georgians whose accomplishments and community service reflect the highest ideals of the founding body of Trustees.