William McIntosh was a controversial chief of the Lower Creeks in early-nineteenth-century Georgia. His general support of the United States and its efforts to obtain cessions of Creek territory alienated him from many Creeks who opposed white encroachment on Indian land. He supported General Andrew Jackson in the Creek War of 1813-14, also known as the Red Stick War, which was part of the larger War of 1812 (1812-15), and in the First Seminole War (1817-18). His participation in the drafting and signing of the Treaty of Indian Springs of 1825 led to his execution by a contingent of Upper Creeks led by Chief Menawa.

Photograph by Melinda Smith Mullikin, New Georgia Encyclopedia

William McIntosh Jr., also known as Tustunnuggee Hutkee (“White Warrior”), was born around 1778 in the Lower Creek town of Coweta to Captain William McIntosh, a Scotsman of Savannah, and Senoya, a Creek woman of the Wind Clan. He was raised among the Creeks, but he spent enough time in Savannah to become fluent in English and to move comfortably within both Indian and white societies.

McIntosh was related by blood or marriage to several prominent Georgians. Governor George Troup was a first cousin, and Governor David B. Mitchell was the father-in-law of one of McIntosh’s daughters. McIntosh married three women: Susannah Coe, a Creek; Peggy, a Cherokee; and Eliza Grierson, of mixed Creek and American heritage. Several of his children married into prominent Georgia families. These marriages helped to solidify McIntosh’s political alliances and his loyalty to the United States.

Image from Archives and Rare Books Library, University of Cincinnati Libraries

McIntosh was among those who supported the plans of U.S. Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins to “civilize” the Creeks. Slaveowning, livestock herding, cotton cultivation, and personal ownership of property were examples of changes to traditional Creek ways of life that McIntosh promoted. He himself owned two plantations with enslaved laborers, Lockchau Talofau (“Acorn Bluff”) in present-day Carroll County, and Indian Springs, in present-day Butts County. Both are maintained today as historic sites. While McIntosh’s support of white civilization efforts earned him the respect of U.S. officials, more traditional Creeks regarded him with distrust.

McIntosh’s support of the United States in the Creek War of 1813-14 earned him the contempt of many Creeks. He was instrumental in the United States’ victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, where he led a contingent of Lower Creeks against the Red Sticks, who were primarily Upper Creeks opposed to white expansion into Creek territory. As a result of the U.S. victory at Horseshoe Bend, both Upper and Lower Creeks were forced to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, in which the Creeks ceded 22 million acres of land in Alabama and south Georgia to the United States. In the wake of that war, the Creeks suffered famine and deprivation for several years. During that time McIntosh allied himself with Indian agent David B. Mitchell, Hawkins’s successor, to coordinate the distribution of food and supplies from the U.S. government to the Creeks. This alliance assured McIntosh’s control over resources and his continued influence among the Creeks.

In 1821 John Crowell replaced Mitchell as Indian agent. Crowell severed McIntosh’s access to resources, weakening McIntosh’s influence among the Creeks, who were compelled to sell some of their land to pay debts and to acquire food and supplies. However, for his role in the first Treaty of Indian Springs, in 1821, McIntosh received 1,000 acres of land at Indian Springs and another 640 acres on the Ocmulgee River.

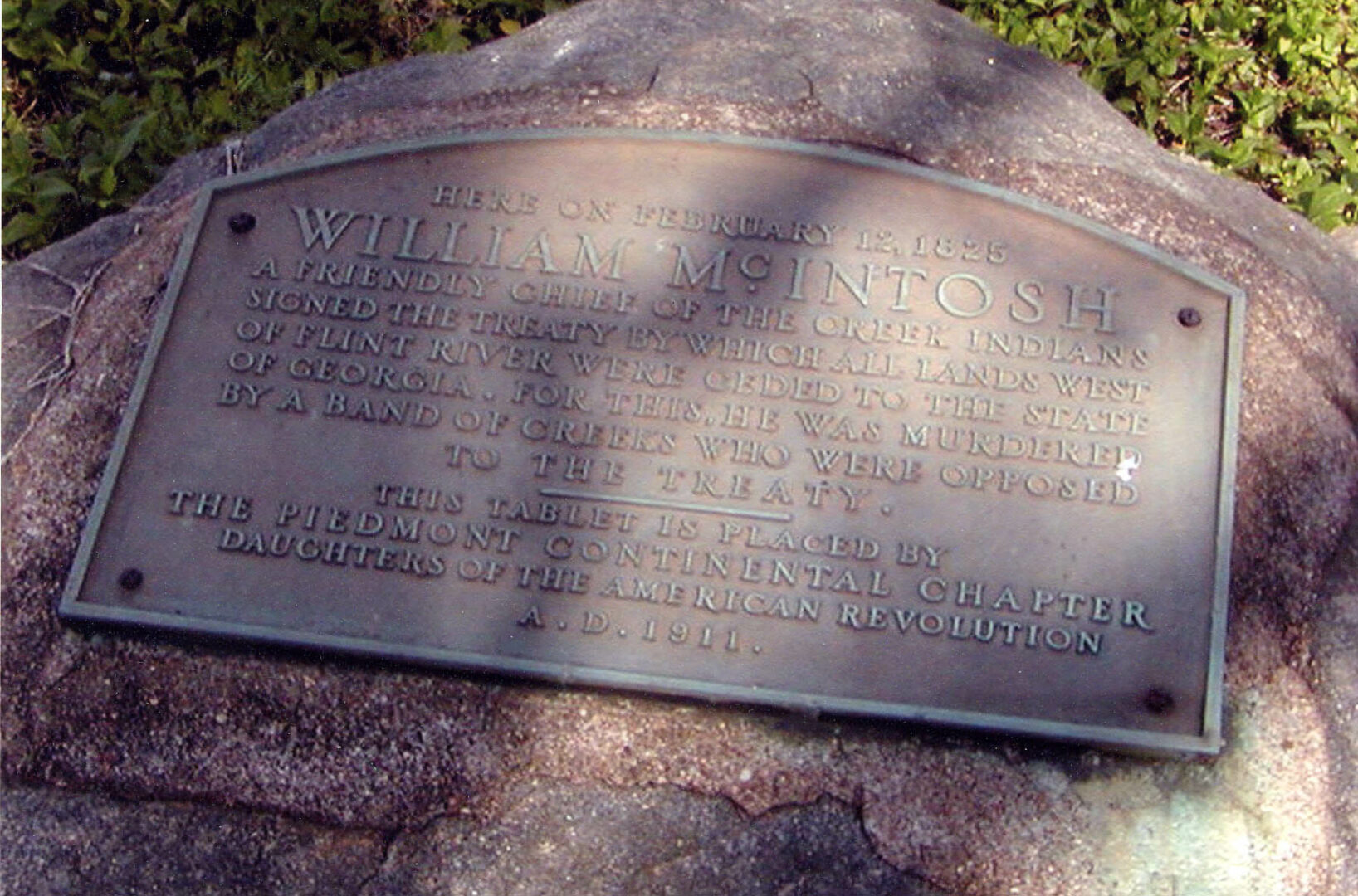

After that treaty, Governor George Troup was determined to enforce the Compact of 1802 that called for the extinguishment of all Indian titles to land in Georgia. Despite the fervent opposition of many Upper Creeks, and with Troup’s assurances of protection, Chief McIntosh, together with a small contingent of mostly Lower Creek chiefs, negotiated the second Treaty of Indian Springs, in 1825. This treaty provided for the cession of virtually all Creek land remaining in the state of Georgia in exchange for a payment of $200,000. A controversial article in the treaty provided additional payment to McIntosh for the lands granted to him in the 1821 treaty. On February 12, 1825, only six chiefs, including McIntosh, signed the document. McIntosh’s motives have since been debated. His supporters suggest that he acted pragmatically, believing that the Georgians’ relentless demand for Creek land made its loss inevitable. His detractors suggest that he acted to spite his enemies, flouting Creek law and profiting personally.

Whatever his motivations were, McIntosh’s participation in the 1825 Treaty of Indian Springs cost him his life. According to a Creek law that McIntosh himself had supported, a sentence of execution awaited any Creek leader who ceded land to the United States without the full assent of the entire Creek Nation. Just before dawn on April 30, 1825, Upper Creek chief Menawa, accompanied by 200 Creek warriors, attacked McIntosh at Lockchau Talofau to carry out the sentence. They set fire to his home, and shot and stabbed to death McIntosh and the elderly Coweta chief Etomme Tustunnuggee.