Located in the northwest corner of Georgia, Sand, Lookout, and Pigeon mountains belong to the geologic province known as the Appalachian, or Cumberland, Plateau. This plateau extends continuously from New York to Alabama and forms the western boundary of the Appalachian Mountains. The area has great economic significance because the vast Appalachian coalfield lies beneath it. Only a small segment of the plateau lies in Georgia, and yet this area is one of the most scenic in the state. A visit to Cloudland Canyon State Park, in Dade County, or to Point Park, on Lookout Mountain in neighboring Tennessee, provides spectacular views from the sandstone bluffs that form the edge of the plateau.

Image from Andy Montgomery

The rocks of the Appalachian Plateau are sedimentary rocks of similar age and type to those found in the Valley and Ridge province to the southeast. The fossils they contain belong to the Paleozoic era and were deposited in shallow seas between the Cambrian and Pennsylvanian periods (540-300 million years ago). Like the rocks of the Valley and Ridge, the Appalachian Plateau was uplifted during the mountain building that formed the Appalachians. However, deformation was less severe, and the folds and faults so characteristic of the Valley and Ridge province die out under the plateau. The plateau is interrupted by several north-northeasterly trending valleys: Lookout Valley; McClemore Cove; Sequatchie Valley (longest of them all), which stretches further northwest into Alabama and Tennessee; and Wills Valley, which extends into Alabama. These valleys have been eroded into limestones and shales exposed along the crests of great folds. Dating from the Cambrian through Devonian periods (542-359 million years ago), these are the oldest rocks exposed in the plateau country. The plateaus, which are actually the flattened bottoms of giant folds of rock, preserve younger rocks from the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian periods (359-299 million years ago).

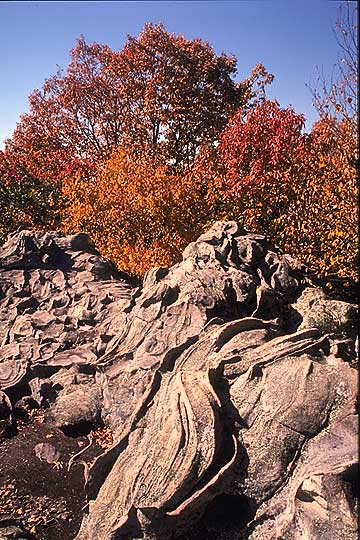

Photograph by Pamela J. W. Gore

At the base of the Mississippian-Pennsylvanian section is a distinctive black shale, the Chattanooga Shale, which dates to the Devonian. It is less than ten meters thick but forms a useful and distinctive marker for geologic mapping. Because of its weakness relative to the overlying limestones, low-angle thrust faults produced during folding commonly flattened out and propagated through the Chattanooga Shale. As a consequence, throughout the plateau country in Georgia, Mississippian and Pennsylvanian strata are detached from older strata by a major subhorizontal thrust fault.

The Mississippian rocks are dominantly limestones and house a famous labyrinth of caves that developed as a result of solution weathering by slightly acidic groundwater. The Pennsylvanian rocks, on the other hand, are mainly sandstones and shales. The resistant sandstones protect the high plateaus from erosion. The resulting topography is an exact reversal of the underlying rock structure; the upfolds form valleys, and the downfolds form the mountain plateaus.

Limestones in the valleys are full of tropical marine fossils, but the fossils of Pennsylvanian sandstones and shales yield abundant plant leaves and stems. During Pennsylvanian times, shallow seas were being overwhelmed by deltaic sediments shed by the rising Appalachian Mountains. In some places, enough plant debris accumulated to form peat, which upon burial, heating, and compaction was converted to the coal of the Appalachian coalfield.

Other mineral commodities mined in the area include limestone, still mined for cement and aggregate, and ironstone, long since exhausted. Thus the plateau country offered a similar combination of iron ore, coal fuel, and limestone flux to that found near Birmingham, Alabama. In the early 1900s there were thriving blast furnaces at Chattanooga, Tennessee; Gadsden, Alabama; and Rising Fawn, Georgia. However, although similar in age and origin, the iron seams in Georgia were much thinner than those in Alabama and were soon depleted.

A curious natural feature of the plateau country is the development of rock towns. The most famous is Rock City, Tennessee, but the crest of Pigeon Mountain in Georgia is another excellent example. In both cases a jumble of sandstone blocks is separated by a maze of “streets.” Careful mapping shows that the sandstone layers are interbedded with shales. Given a gentle slope and water for lubrication, the sandstones break into blocks that slide slowly apart over the weaker shales. Around the edges of the plateau these blocks have often tumbled down the slopes as immense landslides.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

For early settlers moving west into Tennessee and Kentucky, the Cumberland escarpment on the east side of the Appalachian Plateau formed a major obstacle. The southeast sides of Lookout and Pigeon mountains forms the equivalent feature in Georgia. However, in the southern Appalachians, the Tennessee and Coosa river valleys provide natural gaps and routes to the interior. Settlers utilized these gaps for access to rich farm lands in the limestone valleys (Lookout, Sequatchie, and Wills) and generally avoided the plateau country, where the soils were thin and acidic. Apart from a few old coal-mining communities, such as Durham in Walker County, most settlement occurred in such valleys as Trenton Valley in Dade County. This pattern continues to the present day but with increasing housing development along the scenic bluffs overlooking the valleys.