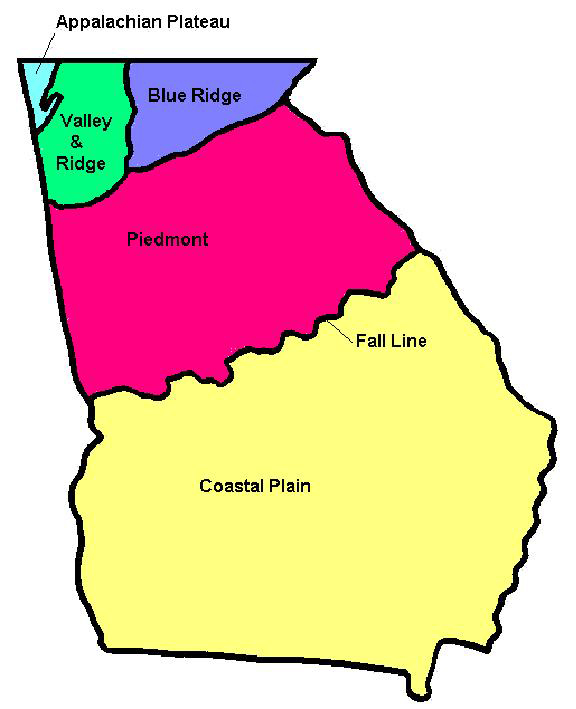

The Valley and Ridge is the westernmost physiographic province of the Appalachian Mountains, bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge, the south by the Piedmont, and the northwest by the Appalachian Plateau. It is characterized by long north-northeasterly trending ridges separated by fertile valleys and extends continuously from New York to the edge of the Coastal Plain (fall line) in Alabama. Much of northwest Georgia lies within the Valley and Ridge province.

Topography

The province owes its topography to the erosion of alternating layers of hard and soft sedimentary rock that were folded and faulted during the building of the Appalachians. Thus, the topography strongly reflects the underlying geology. Ridges are developed on resistant layers of sandstone or chert; valleys are underlain by shale or limestone. Sandstone and chert form thin acidic soils, which support wooded areas on the ridges’ steep slopes. By contrast, shale and especially limestone provide thicker, more fertile lowland soils.

Courtesy of Pamela J. W. Gore

The distribution of ridges and valleys played an important part in the westward expansion of the American colonies during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and it continues to influence patterns of land use, settlement, and communication. In particular, a series of natural gaps running northwest from Cartersville through Calhoun, Dalton, and Ringgold provides access to the Tennessee Valley at Chattanooga, Tennessee. This route strongly influenced colonial-era migration in the South as well as the advance of Union armies during the Civil War (1861-65), and it continues to be a major railroad and interstate corridor.

Geologic Traits and Formation

The geologic division between the Blue Ridge and Piedmont provinces is precisely limited by the outcrop of the Cartersville and Great Smoky faults that separate sedimentary rocks in the northwest from metamorphic rocks in the southeast. However, to the northwest the geologic division is less distinct. Traditionally the Appalachian Plateau is drawn to include the flat-topped Sand, Lookout, and Pigeon mountains, but folding continues into the Sequatchie Valley of Tennessee and Alabama.

Courtesy of Tim Chowns

Throughout both the Valley and Ridge and the Appalachian Plateau, the geology is dominated by a succession of Paleozoic sedimentary rocks deposited when eastern North America was flooded by the ancient Iapetus Ocean. The continent lay close to the equator, and sequences of shallow-marine limestone and shale were deposited with occasional incursions of deltaic or shallow-marine sandstone. In order of age, from oldest to youngest, these Paleozoic-era rocks make up the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Mississippian, and Pennsylvanian systems, which spanned from 542 to 299 million years ago.

During Cambrian and Early Ordovician times, the source of sandstone and shale (sands and muds indicating eroded land) lay toward the center of the continent, but from the Middle Ordovician time the source shifted to the east. This change in sediment source indicates, as does such other evidence as the occurrence of volcanic ash beds within Middle Ordovician rocks, both that the Iapetus Ocean was beginning to close as a consequence of subduction (when one plate descends below the edge of another) and that mountain uplift was occurring at the continental margin. The process culminated in the Pennsylvanian and Permian periods when Gondwana (a supercontinent made up of Africa, South America, and other now separate continents) collided with North America. Intensely deformed metamorphic rocks, created by collisions at the continental margin, were thrust onto the continent and rode over a blanket of buckled sedimentary rocks. These sedimentary rocks now make up the Valley and Ridge Province, while metamorphosed rocks from the continental margin occur in the Piedmont and Blue Ridge provinces. Deformation is most severe within the metamorphic rocks of the Piedmont and gradually decreases in intensity going westward across the Valley and Ridge, until the folds and faults die out beneath the Appalachian Plateau.

Photograph by Pamela J. W. Gore

Photograph by Pamela J. W. Gore

During the Paleozoic era, the Iapetus Ocean was converted from an ocean resembling the Atlantic, with passive continental margins (during the Cambrian and Early Ordovician), to an ocean surrounded by subduction zones, earthquakes, and a ring of fiery volcanoes like those around the Pacific (Middle Ordovician and Pennsylvanian). During the Permian period, a continental collision known as the Alleghenian orogeny built a mountain range rivaling the modern Himalayas, which are the result of a more recent continental collision.

Present-Day Exposure

Mountain building ended some 250 million years ago, and by 200 million years ago the Atlantic Ocean was beginning to open. Two hundred million years of weathering and erosion have taken their toll on the Appalachians and upon the folded and faulted structures of the Valley and Ridge. Thousands of feet of strata have been removed from the valleys (slightly less from the ridges) and have been delivered to the Gulf of Mexico by rivers like the Tennessee. The crests of anticlinal, or convex, folds have been breached by erosion to expose the oldest Cambrian strata. Younger rocks dating from the Pennsylvanian period are still preserved in down-folded synclines, or concave folds, like those that form Lookout and Pigeon mountains. If ever deposited, Permian strata have been removed altogether.

Like the weathering of an old wooden plank, erosion has etched the north-northeasterly trending folds, formed by collision and crustal shortening, into valleys and ridges. A northwesterly traverse across the Valley and Ridge (along Interstate 75, for example) reveals tilted layers of Paleozoic sedimentary rock that represent the limbs of these dissected folds. The spectacular Blue Ridge escarpment, north and west of Cartersville, marks the southeasterly dipping faults, formed where metamorphic rocks slid over folded sedimentary rocks. Closer to Chattanooga the folds almost die out, and the strata are almost horizontal, although they are still more than 1,000 feet above the elevation at which they were originally deposited.