The lure of making money from cotton and the waterpower of the Chattahoochee River shaped the Muscogee County seat of Columbus for more than a century after the Georgia legislature created the city in 1828.

Located at the head of river navigation, Columbus first boomed as a cotton-trading center. Entrepreneurs quickly harnessed the river’s power, and Columbus became one of the South’s earliest—and remained one of its largest—mill towns. The creation of neighboring Camp Benning (later Fort Benning and now Fort Moore) in 1918 added another dimension to the city. By the 1960s Columbus began shedding the image of a mill and military town, as its business and civic leaders diversified the economy, modernized its government, and launched a series of cultural initiatives. By 2000, as the city rediscovered its picturesque river, private and public funding revitalized the original downtown into a premier venue and educational center for the fine and performing arts.

Antebellum Years

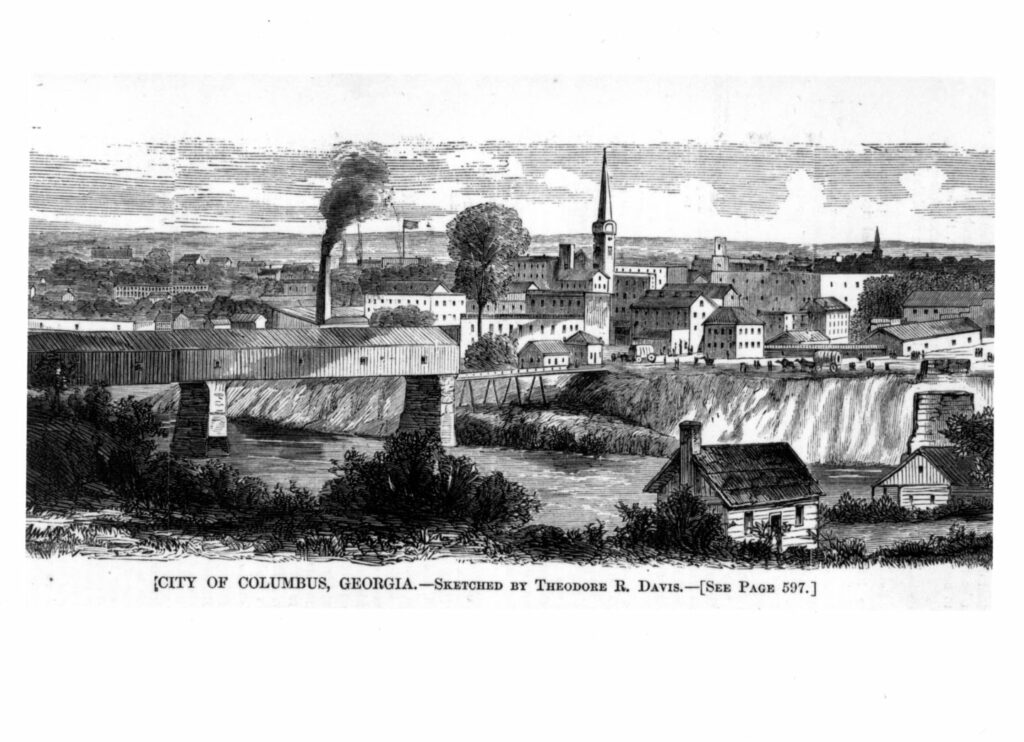

In 1828 the state legislature, realizing the economic potential of a location on the Chattahoochee River at the fall line, planned the city and auctioned its lots. The author Washington Irving’s contemporary writings about explorer Christopher Columbus probably influenced its naming. The original town consisted of a rectangle, thirteen blocks north to south (from the river to Seventeenth Street) and nine blocks east to west (from the river to Sixth Avenue), nestled against the irregular bank of the river on the west and south. A four-block commons area or greenspace surrounded it on the north, east, and south.

The town retained a frontier atmosphere for more than a decade. The Creek Indians clung to a strip of land west of the river, and outlaws tended to seek refuge there, where federal authority proved ineffective. The 1836 Creek War forced the final removal of 16,000 Indians, in an event now known as the Trail of Tears (1838-39). The subsequent availability of land reinforced the obsession about making money from cotton, but only a few realized the dream of becoming wealthy planters. Columbus warehouses and merchants served planters and farmers within a fifty-mile radius. Initially the river linked the city’s economy via Apalachicola, Florida, to the world cotton market, primarily to Liverpool, England.

The river’s commercial advantage diminished in the 1850s with the arrival of railroads (via branch lines from Fort Valley and from Opelika, Alabama). Steamboats still plied the Chattahoochee, but rails began connecting Columbus with larger markets. The emerging rail center of Atlanta eclipsed Columbus as the western metropolis of Georgia.

The Chattahoochee’s waterpower made Columbus a manufacturing center. The river powered gristmills and sawmills as early as 1828 and a textile mill north of town by 1838. The city of Columbus, which controlled the greatest potential waterpower site in the South, never spent any public money developing this resource. Rather than building a canal to deliver waterpower to various locations within the city (such as Augusta did), Columbus simply sold the rights to dam the river and restricted the use of the resulting power to a two-block area along the Chattahoochee (between present-day Twelfth and Fourteenth streets). That decision limited the city’s early industrial development. Even so, by the 1850s five water-powered mills produced textiles, flour, and sawn lumber, and at other locations fourteen smaller companies produced a variety of goods. In 1853 the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, an indefatigable traveler and astute observer, declared Columbus the largest manufacturing city south of Richmond, Virginia.

By 1860, 9,621 white and Black Columbusites resided within 120 square blocks. This total included 955 industrial workers who lived in tenements next to the “Golden Row” mansions that lined the waterfront. In the late 1850s the industrialists financed abridge (at present-day Fourteenth Street) to move the textile workers to Alabama. Since Georgians owned both sides of the river, no mills or wharfs developed in Alabama, and the west bank remained a suburb rather than a rival town. Olmsted noted that Columbus was a rough city and advised travelers not to stop there.

In 1860, 3,547 enslaved and 141 free Black people lived throughout the city. Another 557 whites and 912 enslaved people lived in Wynnton, the suburb nestled atop the hills east of the city. Wealthy families built Greek revival and Italianate estates in this elevated area, which residents considered healthier than the riverfront. The census ranked Wynnton as the sixteenth largest town in Georgia in 1860.

Civil War and Reconstruction

Columbus reached its apogee during the 1860s. Its population ranked third among Georgia towns in 1860 and fifteenth among those joining the Confederacy. Its industrial output ranked tenth in the South, with its textile production probably second or third. Both its population and its manufacturing capacity increased during the Civil War (1861-65), but after 1865 Columbus never again equaled those rankings except in textile production.

The city divided over the issue of secession in 1860-61, but eventually the voters supported it. By 1862 the city had sent eighteen companies (1,200 men) to the Confederate army. The city’s most famous soldier was General Henry L. Benning.

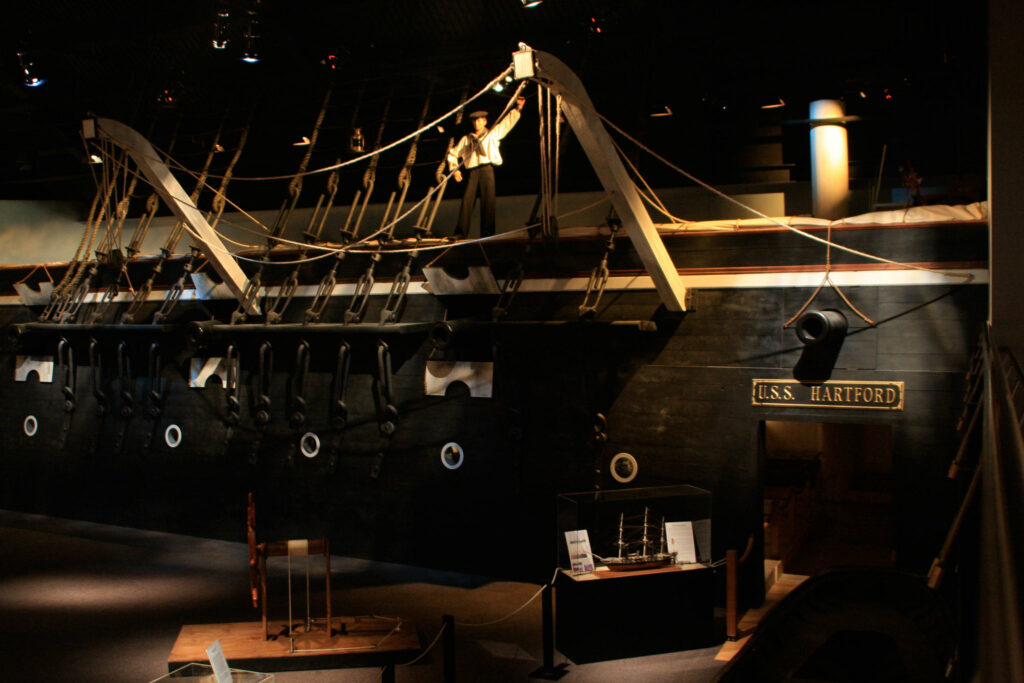

Columbus immediately expanded its industrial output and soon ranked among the top five Confederate producers. Factories tripled their output and shifted to war-related products. Storekeepers boarded up their windows and began making drums, fifes, India rubber cloth, and sewing tents and uniforms. Various branches of the Confederate government confiscated existing facilities and created their own operations: clothing and wagon establishments, the South’s largest shoe factory staffed by Black labor, the Columbus Arsenal, the Confederate Naval Iron Works, and the Navy Yard. The Iron Works produced steam engines for ships, while the Navy Yard built the ironclad Muscogee. The need for workers pushed the city’s population from 10,000 to 15,000.

Columbus escaped some of the war’s impact. Since Union general William T. Sherman’s army never reached the city, casualties from the fighting around Atlanta, during the Atlanta campaign, were evacuated to hospitals in Columbus. Eventually seven buildings—stores, saloons, churches, and the courthouse—served as hospitals.

The city’s industries attracted General James H. Wilson’s Union raiders (13,500 cavalrymen armed with repeating rifles) on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865—one week after Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Virginia. Unaware of that event, Confederate home-guard units attempted to stop the raiders in the hills east of Columbus. Wilson surprised the defenders by attacking at night. Amid the ensuing chaos, the untrained Southerners fled, to be joined by the Union soldiers in a mad dash for the bridge to Columbus. Wilson lost 25 men, while his troops captured about 1,500 Confederates and killed 9. Later, Columbus boosters proclaimed this as the war’s last battle. Over time they continued qualifying its title until this skirmish became “The Last Land Battle of the War Between the States East of the Mississippi.”

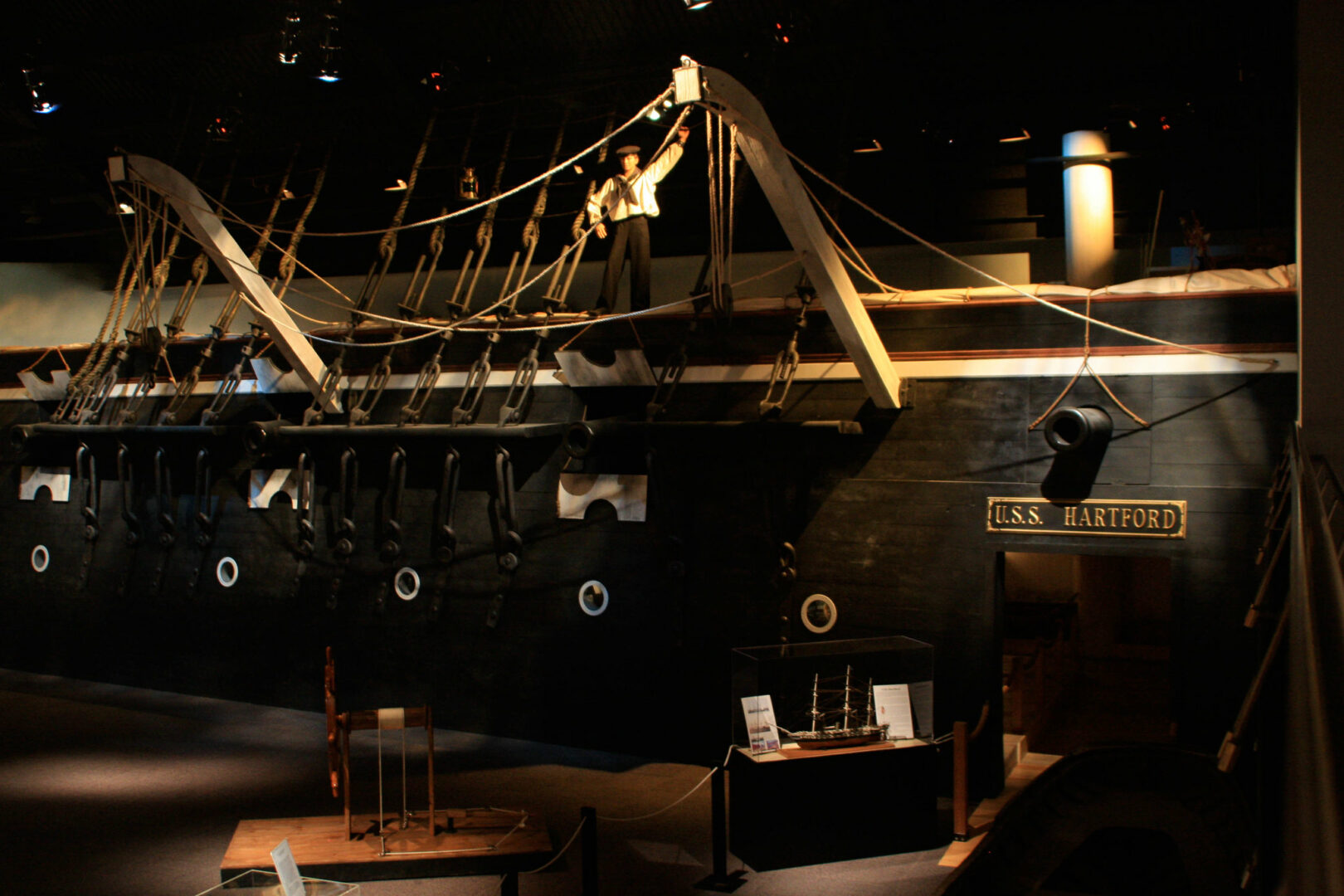

The day after the battle, Wilson’s troops torched the city’s industries. The remains of the hull of the ironclad Muscogee now form the centerpiece of the Port Columbus Civil War Naval Center. As the fires raged and Wilson’s troops headed toward Macon, a mob composed of whites, formerly enslaved people, and some Union soldiers looted the stores on Broad Street.

At war’s end U.S. president Andrew Johnson named his friend and fellow Unionist James Johnson, a Columbusite, as provisional governor of Georgia. Local Reconstruction was marked by a violent confrontation with Black Union troops in February 1866 and the Ku Klux Klan –style murder of George Ashburn, an outspoken Scalawag (local Republican) in 1868. Reconstruction brought free schools to the city. Since the Freedmen’s Bureau created Black schools, white leaders finally moved to establish public schools in 1867. Freedmen from rural areas built shanties on the East Commons. Despite harassment from locals and white federal troops, the Black community persevered and created a vibrant neighborhood in the southeast corner of the city known as “Sixth and Eighth” (Avenue and Street respectively). The city’s most important Black churches are still in this area. Gertrude “Ma” Rainey , a Columbus native recognized as the mother of blues, purchased a home in this area and retired here in the mid-1930s.

Industrial Expansion

Industrial reconstruction began immediately after 1865. R. L. Mott, a prominent Unionist (whose home still stands along the riverbank just north of Fourteenth Street), controlled the local Republican Party and the city during Reconstruction. As an entrepreneur, Mott simply joined with ex-Confederate and Democratic businessmen to rebuild. Local newspaper editors, fifteen years before Henry W. Grady, promoted industrialization, sectional reconciliation, and even racial harmony (but not equality).

Both small and large entrepreneurs immediately rebuilt their enterprises. Foundries started producing by June, and textile mills were in back in operation by December 1865. By 1870 more than 100 manufacturers operated within the city, but the small nontextile companies languished in that decade. One-fifth of them failed, buffeted by the crash of 1873 and unable to compete in the new railroad-linked national market.

Textiles, on the other hand, flourished; their production expanded by 339 percent in the 1870s. William H. Young’s Eagle and Phenix Company launched mills in 1866, 1869, 1872, and 1876, quadrupling its output in ten years. By 1880 only two counties in the South produced more textiles than Young’s mills in Muscogee County. Locally they manufactured 80 percent of the textiles, employed 65 percent of the total labor force, and used 95 percent of the waterpower.

George Parker Swift’s Muscogee Mills used the other 5 percent of the waterpower. Swift’s factory began on one waterpower lot (1868 and 1880) and then expanded north of Fourteenth Street, with new mills appearing in 1887, 1904, 1916, 1926, and 1950. Young’s and Swift’s mills became the foundations of two dynasties. Their economic descendants (primarily W. C. Bradley and G. Gunby Jordan) eventually controlled every local textile enterprise and created seven mills, four banks, and the Columbus Power Company; Swift’s family and in-laws (Epping, Illges, Kyle, Spencer, Swift, and Woodruff) developed seven mills and three banks through the 1970s.

As the city’s economy expanded, industries moved into the remaining land on the East Commons, and middle-class suburbs grew in Wynnton, which was first served by streetcars and then by automobiles. At the same time, other Columbusites fought for reform. Helen Augusta Howard, who inherited her family’s home, chafed because she paid taxes without representation. Howard became a suffrage activist and established the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association in 1891. Prince W. Greene, a local weaver, served as president of the National Union of Textile Workers (1898-1900) and moved its national headquarters to Columbus.

Twentieth Century

Other leaders created educational and cultural institutions. Private endeavors established free kindergartens for mill children (1895) and for African Americans (1903), as well as a school for the “dinner-toters” who delivered lunches to the mills (1901)—all of which the public schools absorbed before creating a secondary industrial school (1906). The city also gained a Carnegie public library (1907).

Progressive mayor L. H. Chappell (1897-1907 and 1911-13) modernized the city. During the Spanish-American War (1898) he lured a military training camp to town, paved and curbed downtown streets, built sewers and steel bridges, planted trees, and created the modern municipal water works, which transformed the muddy Chattahoochee into drinking water.

World War I (1917-18) brought social upheaval and long-term changes. Encouraged by the National War Labor Board, Columbus textile workers in 1918 organized and successfully struck to force the rehiring of union members. In February 1919, 7,000 Columbus operatives walked out as part of a national strike, demanding an eight-hour day. In May 1919 anti-unionists fired on a union rally, killing one, wounding seven, and breaking the most serious attempt to organize local workers.

In September 1918 the U.S. War Department created Camp Benning, located on Macon Road near what is now the public library. Extensive lobbying efforts resulted in a permanent camp, Fort Benning, in 1922. The name was changed to Fort Moore in 2023, to honor Lieutenant General Harold “Hal” Moore and his wife, Julia Moore. For almost twenty years Fort Benning functioned primarily as a training center for infantry officers. The influx of those officers made Columbus, or at least its middle class, more worldly. During World War II (1941-45) the post assumed a more expanded mission.

In 1919 Ernest Woodruff, a Columbus native and Atlanta businessman, engineered the purchase of Coca-Cola from the Candler family for $25 million. W. C. Bradley, who was chair of the board of Coca-Cola for twenty-seven years, served as Woodruff’s partner, selling stock to friends and acquaintances, primarily in the Chattahoochee Valley. That investment still pays significant dividends to the community.

In 1922 Columbus became the first major southern city to adopt the commission–city manager form of government in large measure because the newly enfranchised women supported this reform and served on the first commission. In 1926 the editor of the Columbus Enquirer-Sun, Julian Harris, son of Joel Chandler Harris, won a Pulitzer Prize for his fight against the revived Ku Klux Klan at both the state and local level.

The city’s economy diversified in the 1920s. The Tom Huston Peanut Company (later named Tom’s Foods) opened and began selling Tom’s Toasted Peanuts. The neighboring company of Claud Hatcher began producing Chero-Cola in 1905, Nehi in 1924, and Royal Crown Cola in the 1930s. By the 1920s, however, Columbus lost control of its most important asset—the Chattahoochee’s waterpower. Goat Rock Dam (1912) and Bartlett’s Ferry Dam (1926), north of the city, produced electricity for Columbus’s rivals: West Point, LaGrange, and even Atlanta.

By 1927 the city had entered the Great Depression as the demand for cotton textiles plummeted. In the 1930s several Columbus mills borrowed money from New York banks to continue running. Construction at Fort Benning also provided much-needed jobs. By 1940 Fort Benning was brimming with activity. In neighboring Phenix City, Alabama, bar girls, brothels, and gaming tables fleeced soldiers and earned it the title of “Sin City, USA.” These rackets continued until the 1954 assassination of the Alabama attorney general–elect, Albert Patterson, finally produced a concerted cleanup.

Meanwhile, a Greater Columbus Committee outlined new goals. These resulted in consolidating the county and city schools in 1949 and establishing Columbus College (later Columbus State University) in a closed mill in 1958. Until that time Columbus was the largest southern city without a college. In 1961 the Columbus Area Vocational-Technical School (later Columbus Technical College) was founded.

During the 1940s, a more significant movement—which eventually liberated the city and the South—was occurring at the grassroots level. Primus King, a local African American, challenged the all-white Democratic Party primary in 1944, and the federal courts ordered the integration of that election. A few years later, the 1956 shooting death of Thomas Brewer, a local leader of the civil rights movement, caused some of the Black elite to leave, but those who stayed continued the struggle. In 1964 Albert Thompson won a seat in the legislature, and other African Americans followed him into local offices, some as Republicans.

J. R. Allen, a young businessman, organized a biracial Republican Party and became mayor in 1968. He led the consolidation of the city and county governments—the first such action in Georgia. The city doubled its size in 1970 and absorbed the remaining county areas the next year because Allen convinced the legislature to hold referendums that favored the city. The new government began in 1971 with Allen as mayor and A. J. McClung, an African American, as mayor pro tempore.

Recent Development

By the 1970s the economy had changed. Local businessmen stopped excluding new industries that might raise local wages and began seeking new manufacturers, such as Dolly Madison Bakery (1970) and Pratt and Whitney (1984), which made jet engine parts. But local initiative created the most dynamic enterprises—Aflac Insurance, Synovus Financial Corporation, and Total System Services. Total System Services (TSYS), credit card processors, destroyed the old Muscogee factories to build their new campus, but their new clerical mills paid better wages.

The historic preservation movement began in the mid-1960s, when the 1871 Springer Opera House, a National Historic Landmark and now the State Theatre of Georgia, was threatened with demolition. The young activists who saved it then organized the Historic Columbus Foundation and created historic districts in the southwest corner and the uptown area of the original city and in the Wynnton suburbs, and the National Historic Landmark industrial district along the river.

A continuity of historic space has been preserved in the South Commons (1828), the site of such public recreation as early horse and automobile racing. It now includes Golden Park (a minor league baseball park), the A. J. McClung Memorial Stadium (the venue for the Auburn University-University of Georgia football game from 1916 to 1958 and for both the Tuskegee University-Morehouse College and Fort Valley State University –Albany State University games today), the 1996 Olympic softball fields, and the Civic Center (1996), which stages professional hockey, basketball, and arena football. The historical importance of Fort Moore to Columbus was highlighted in 2009 with the opening of the National Infantry Museum and Soldier Center, which is located on city property just outside the post’s gates.

Columbus has also established itself as a center for the fine and performing arts. During the late 1990s the Columbus Challenge raised more than $100 million ($85 million in private donations) to enhance the arts, improve existing cultural venues, and build the stunning RiverCenter for the Performing Arts, which houses Columbus State University’s (CSU) music department and three stages (symphony, organ recital, and studio). In 2002 the community and the university began raising another $80 million. The priorities for using the funds include bringing CSU’s art and drama departments to downtown locations. Such initiatives are providing Columbus with a unique cultural niche and with vibrant, modern architecture mixed with its old brick facades.

Visitors looking for native culinary treats enjoy fried catfish, scrambled dogs (a chopped-up hot dog and bun on oyster crackers completely smothered with chili), smoked pork barbecue with mustard-based sauce, and “country captain” (fried chicken cooked in a tomato sauce with almonds and currants).

In 2003 Columbus renewed its appreciation for the Chattahoochee River. Under federal court order to build a combined sewer-overflow system, the Columbus Water Works developed the Chattahoochee Riverwalk, which follows a fifteen-mile section of the river.

According to the 2020 U.S. census, the population of Columbus is 206,992, an increase from the 2010 population of 189,885. This growth pushed Columbus past Augusta and made it the second largest city in the state.