The study and exploration of caves, known as speleology, has revealed 513 caves in Georgia, and more are being discovered as exploration continues. Documentation by the Georgia Speleological Survey shows that Georgia’s caves have a total combined length of at least 82 miles. However, caves of any significant size are known to exist only in 32 of Georgia’s 159 counties, and most of those caves are in northwest Georgia.

Photograph by Joel M. Sneed

Cave Formation

Most caves form through the dissolution of limestone by acidic groundwater. Limestones of the Paleozoic age are a common bedrock in the Appalachian Plateau and Valley and Ridge provinces of northwest Georgia, and those limestones are riddled with caves and other features formed by solution processes. Georgia’s two northwesternmost counties, Dade and Walker, host 164 and 149 caves respectively. Bartow County and the eight counties to the north and west (Catoosa, Chattooga, Dade, Floyd, Gordon, Murray, Walker, and Whitfield) combine to host 448 of Georgia’s 513 known caves.

Spectacular caves in northwest Georgia include Ellison’s Cave, Pettijohn’s Cave, and Byers Cave. With a depth or vertical extent of 1,063 feet and a length of 64,030 feet (almost twelve miles), Ellison’s Cave in Walker County is the twelfth deepest and fifty-second longest cave in the United States. The two deepest cave drops in the continental United States occur in Ellison’s Cave: “Fantastic,” which drops 586 feet, and “Incredible,” which drops 440 feet. Pettijohn’s Cave, also in Walker County, has more than six miles of passages, and the Byers Cave system in Dade County has passages totaling five and a half miles. These caves contribute to the reputation of the area where Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia meet (known to the caving community as the “TAG” region) as one of the world’s most exciting regions for caving.

Photograph by Willie Hunt

The only other part of Georgia in which limestone bedrock is present is the Coastal Plain of south Georgia. Decatur County in far southwest Georgia has four caves, including Climax Caverns, which has passages totaling more than seven miles. In adjacent Grady County there are five caves, including Glory Hole Caverns, which has almost three miles of passages and is well known for its crystalline gypsum formations. Other caves are scattered through Crisp, Dodge, Dougherty, Houston, Lee, Randolph, Terrell, Turner, Washington, Wilcox, and Worth counties in the Coastal Plain.

Caves can also form in other kinds of bedrock, typically where stream erosion undercuts rock ledges, where faults and fractures in bedrock are enlarged by weathering, or where blocks of talus (or rock debris) bridge small underlying passages. Fourteen caves have thus been reported in marbles, granites, gneisses, and schists of the Blue Ridge and Piedmont. In addition, at least one of Walker County’s caves is a passage through sandstone talus.

Cave Life

Georgia’s caves host many troglobitic organisms (those living only in caves) and troglophilic organisms (those capable of living entirely in caves). These include various flatworms, isopods, amphipods, pseudoscorpions, crayfishes, spiders, millipeds, springtails, cave crickets, flies, beetles, fishes, and salamanders. Frick’s Cave in Walker County is home to Georgia’s only known population of Tennessee cave salamanders. Climax Caverns in Decatur County is home to the rare Georgia blind salamander (Haideotriton wallacei) and the Dougherty Plain crayfish (Cambarus cryptodytes), both of which lack skin pigment as the result of evolution in a lightless environment.

Georgia’s caves are also home to many of the state’s sixteen bat species. Bats use caves as hibernation sites during the winter months and as maternity colonies and bachelor colonies at other times of the year. Many bats are also migratory, and caves serve as crucial daytime habitats during their migrations. Gray bats (Myotis grisescens), an endangered species, are found in Lowry Cave in Chattooga County, Frick’s Cave in Walker County, and Deatons and White River Caves in Polk County. Frick’s Cave is home to as many as 15,000 gray bats.

Courtesy of Georgia Wildlife Federation

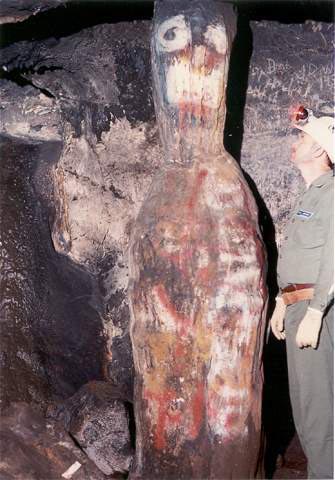

Caves and their wildlife enjoy some legal protection in Georgia, although implementation is largely at the discretion of landowners. The Cave Protection Act of 1977 makes breakage, burning, defacement, or destruction of a cave surface, artifact, or speleothem (cave formations, such as stalactites) without consent of the cave owner a misdemeanor in Georgia. The sale or export of a speleothem without consent of the cave owner is likewise a misdemeanor. Storing or dumping hazardous chemicals, garbage, or animal remains in a cave is a misdemeanor, as is killing, disturbing, or removing wildlife from a cave. Because landowners determine the fate of caves under this law, caves can be stripped or even completely destroyed by quarrying at the discretion of the owner of the land or the owner of the mineral rights to that land.

Cave Exploration

Most caves in Georgia are on private property, and their accessibility is commonly limited. As of October 2002, at least twenty-three Georgia caves in the TAG region were officially closed. Extensive vandalism has led to the erection of barriers at the entrances of some caves, such as Kingston Saltpeter Cave, which is the only cave in Georgia managed as a preserve by the National Speleological Society.

Photograph by Joel M. Sneed

Several caves, including Ellison’s Cave, are in the state-owned Crockford–Pigeon Mountain Wildlife Management Area west of LaFayette. In Cloudland Canyon State Park, Sitton’s Cave is open to the public, but no tours are given, and the cave is very wet for much of the year. Although several caves have been commercialized in the past, Georgia’s only commercial cave in operation in 2003 was Cave Spring Cave in the town of Cave Spring, southwest of Rome and about five miles from the Alabama state line. Cave Spring Cave has a length of 300 feet and a vertical extent of 30 feet.

The principal organization involved in mapping and documenting caves in Georgia is the Georgia Speleological Survey. Grottos, or local chapters, of the National Speleological Society in Georgia include the Athens Speleological Society, the Augusta Cave Masters, the Clayton County Cavers Grotto in Morrow, the Clock Tower Grotto in Rome, the Dogwood City Grotto in Atlanta, the Middle Georgia Grotto, and the Pigeon Mountain Grotto. The Southeastern Cave Conservancy, an organization incorporated in Walker County, seeks to acquire, manage, and conserve caves in the Southeast for scientific, educational, and recreational purposes. By 2003 it owned three preserves in Walker and Dade counties with a total of at least ten caves.