Albany, the seat of Dougherty County, has been the commercial hub of southwest Georgia for most of its history. Although it had competitors, namely Americus, Thomasville, and Valdosta, around the beginning of the twentieth century, Albany remains the urban center of the region. The city supports a significant museum, the Albany Museum of Art, which features one of the largest collections of African art in the Southeast.

Early History

In October 1836 the land speculator and merchant Nelson Tift founded Albany on the banks of the Flint River to serve as a market for recently arrived cotton farmers. Planters and their enslaved African American laborers settled southwest Georgia, which the state had recently acquired from the Creek Indians. By 1840 the Albany region had attracted so many slaveholding farmers that enslaved African Americans outnumbered whites. Over the next two decades the area’s population increased more than fivefold, and a new county—Dougherty—was created in 1853 with Albany as its county seat. Most of the newcomers to Dougherty County were African Americans brought to cultivate its rich cotton lands.

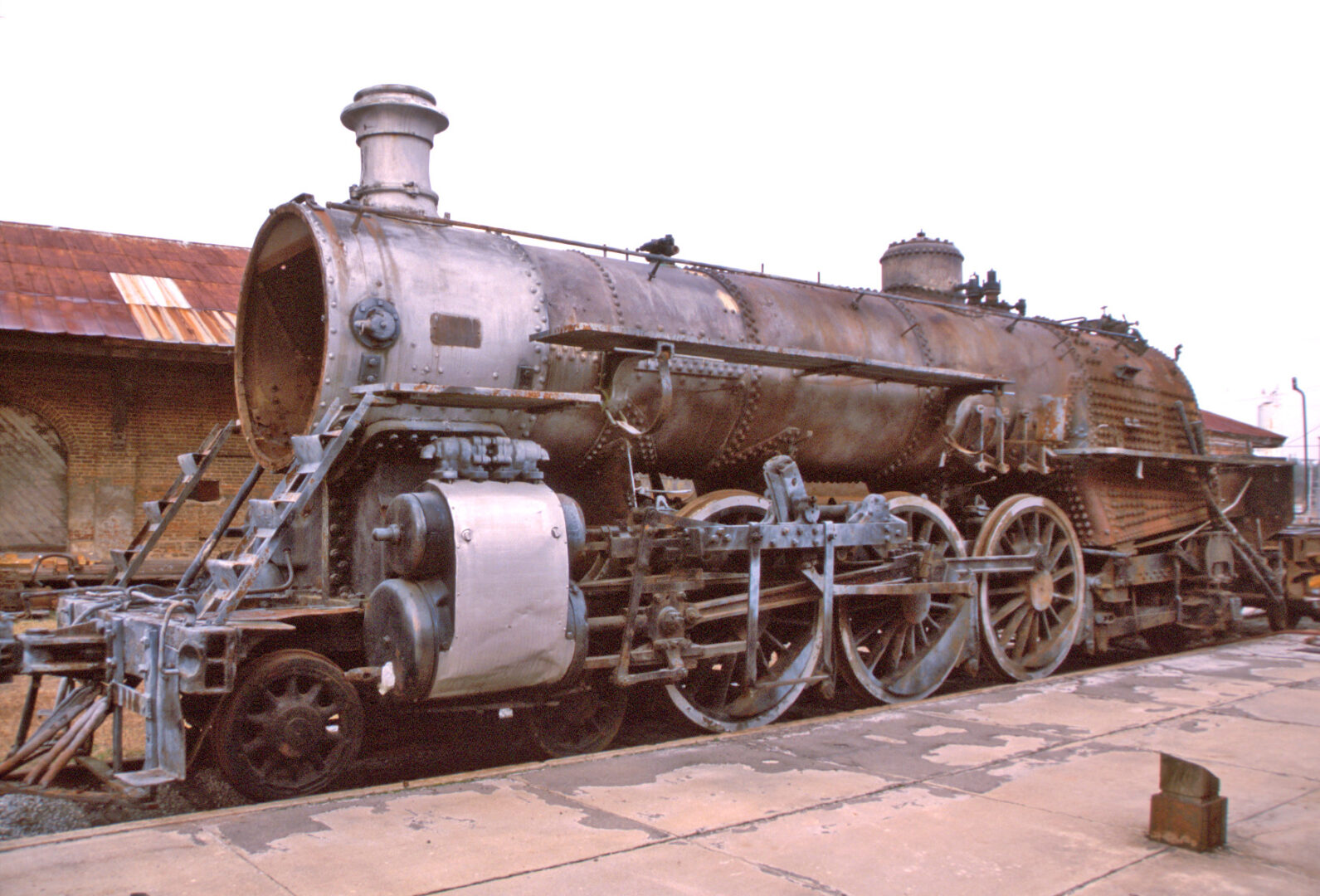

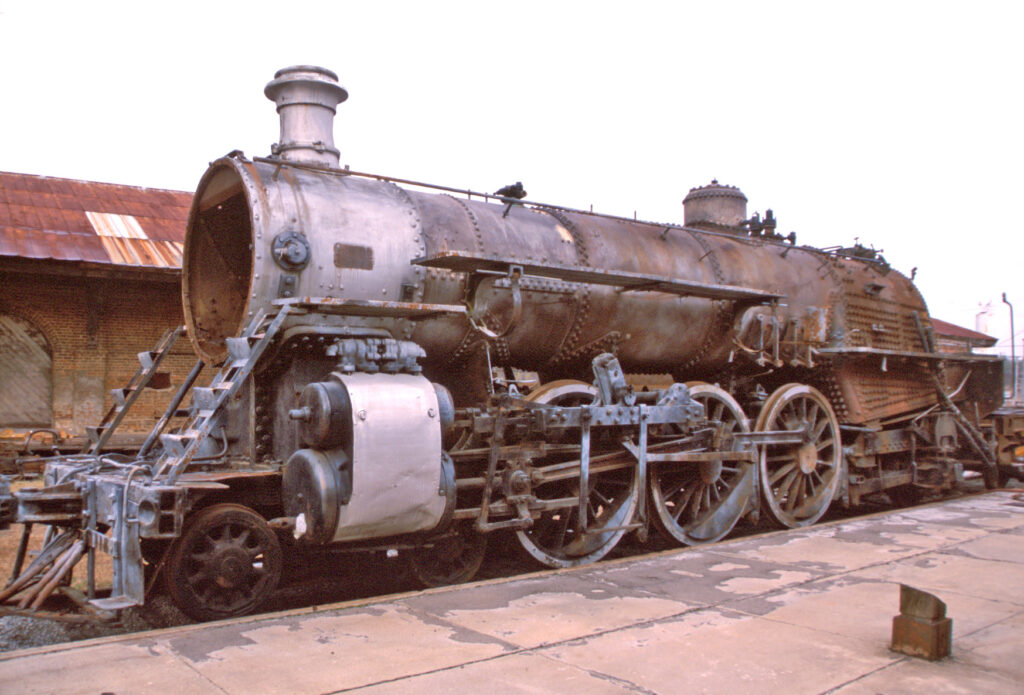

In 1860 Albany’s 1,618 residents made up barely one-fifth of Dougherty County’s population, but the city had become the marketing center for the region’s cotton growers. Its growth and vitality were directly related to the cotton market. In its first two decades the city’s merchants sent barges of cotton down the Flint River to Apalachicola Bay on the Gulf of Mexico. From there the bales of white fiber were shipped to mills in the North and Europe. In 1857 the completion of a rail line to Albany allowed commission merchants to ship cotton to Savannah, a more direct connection to northern and European markets. Eventually Albany would become the rail center of southwest Georgia, with seven railroads serving the community and as many as thirty-five trains arriving and departing daily.

In addition to promoting railroads, Nelson Tift secured a state monopoly for ferry and bridge rights across the Flint River at Albany. Tift hired the African American bridge builder Horace King to erect the covered toll bridge and a bridge house, the entrance to the span. The brick bridge house, nearly a century and a half old, still stands on the west bank of the Flint in downtown Albany.

Although a small cadre of middle-class merchants and professional men dominated antebellum Albany’s society, politics, and economy, the town was a frontier community with a disproportionate number of single men, prostitutes, and bars. A third of its population was African American, but almost all were enslaved. Baptist, Methodist, Episcopal, Presbyterian, and Catholic congregations had each built churches on city lots donated by Tift, but the majority of antebellum residents remained unchurched. Both the Baptist and the Episcopal church had more enslaved members than free whites. A small Jewish community held religious services before the war, but its congregation was not organized until the postbellum era.

After U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, most Albany whites championed secession, and several Confederate military units were organized. Although some of Albany’s soldiers experienced the horrors of Civil War (1861-65) battles in Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere, southwest Georgia itself escaped the ravages of armed conflict. The end of slavery, however, brought revolutionary changes to the region. In 1867-68 more than 2,400 Black men in Albany and Dougherty County registered to vote, and over the next fifteen years they elected three African American legislators to the state legislature. Whites in Albany resisted Black enfranchisement through intimidation and voting fraud, and by 1915 they had succeeded in reducing the number of registered Black voters in Albany to twenty-eight.

Until the 1940s Albany’s population was predominantly African American. The vast majority of Black adults did not own property; the men worked as day laborers and draymen, the women as washwomen and cooks. W. E. B. Du Bois described turn-of-the-century Albany in The Souls of Black Folk (1903): “Six days in the week the town looks decidedly too small for itself, and takes frequent and prolonged naps. But on Saturday suddenly the whole county disgorges itself upon the place, and a perfect flood of black peasantry pours through the streets, fills the stores, blocks the sidewalks, chokes the thoroughfares, and takes full possession of the town.”

Twentieth Century

Agricultural changes in twentieth-century Dougherty County brought significant change to Albany as farmers switched from cotton to more profitable crops. Beginning in the 1890s, farmers began planting pecan trees. In 1922 the Albany District Pecan Exchange completed its factory building and warehouse, and pecans became a major Albany product. Peanuts were another major commercial crop, and shelling and processing plants were built in the city. In the 1930s livestock became important, and in 1936 a large meat-packing plant was built. Meat-processing soon became Albany’s largest industry.

World War II (1941-45) had an important impact on Albany. Two airfields were established to train British and American pilots. Many servicemen assigned to Turner Field decided to stay or return to Albany after the war. The large influx of whites into Albany after 1940 altered the city’s population so significantly that for the first time since the 1870s, African Americans were a minority. Albany experienced its greatest population growth in the 1940s and 1950s, when its total population almost tripled, to 55,890 in 1960. Although African Americans doubled their numbers in Albany during the boom, they could not keep up with the white population, which quadrupled. Between 1960 and 1980, however, the white growth rate plummeted to less than 8 percent, while African Americans https://nge-staging-wp.galileo.usg.edu/articles/history-archaeology/slavery-in-antebellum-georgia increased their numbers by 74 percent.

Geographically, the city expanded steadily in modern times. Occupying a little more than one and a half square miles when it was incorporated in 1838, Albany today consists of fifty-seven square miles. In the 1990s the city saw its first overall population decline, from slightly more than 78,000 in 1990 to just under 77,000 in 2000.

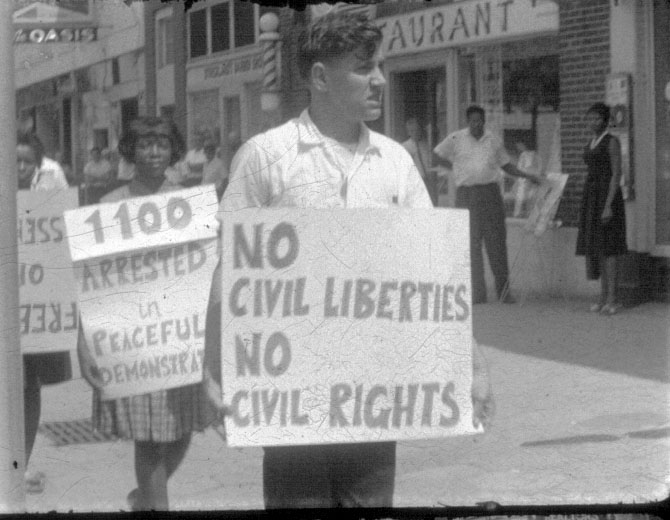

If the central historical event of nineteenth-century Albany was emancipation, the key development of the twentieth century was the civil rights movement. The groundwork for organized protest against segregation in Albany was laid with the establishment of a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People chapter in the wake of World War I (1917-18) and its revitalization in the 1940s.

In the decade and a half after World War II, local activists sporadically challenged the system of Jim Crow. In 1961 several Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) workers came to Albany to help organize the Black community as it challenged segregation. From the start the SNCC workers faced opposition from Black conservatives as well as from whites. Yet at important moments Black residents of Albany rose above these divisions, as they did in November 1961 when they organized the Albany Movement. African Americans had been unsuccessful in their attack on segregation in Albany in 1961-62, but they did increase the number of registered Black voters, and in 1963 the city commission struck its Jim Crow ordinances from the books. The Albany Civil Rights Institute, which opened in 1998, commemorates the movement.

Yet whites continued to control local politics through citywide elections for the city commission. In 1975, however, as a result of a federal court order, district elections for the city commission were held, and two African Americans—Mary Young and Robert Montgomery—won. In 1974 John White became the first Black man to represent Albany in the state legislature in nearly a century. At about the same time African Americans were appointed to the Dougherty County schoolboard for the first time.

Albany’s mid-twentieth-century population growth extended the city’s boundaries and affected affluent neighborhoods near downtown. Business and commercial establishments expanded toward the northwest, and the downtown began to deteriorate. With the opening of the Albany Mall in 1976, long-established firms closed their downtown stores. Mayor James H. Gray Sr. led an effort to revitalize the downtown area by constructing a 10,240-seat civic center and by razing an entire city block in the heart of downtown with plans to rebuild it. His sudden death in 1986 briefly interrupted the Central Square project. Finally, a decade and a half later, much of the block was filled in with a new city-county administration building, a county education administration building, new parking facilities, and a new federal courthouse dedicated to one of Georgia’s best known civil rights attorneys, C. B. King. Adjacent to Central Square, a former four-story retail store was renovated to serve as the county’s central library, and the dilapidated municipal auditorium, restored at a cost of $4 million, was reopened in 1990 with a concert by Albany native Ray Charles.

Following World War II, several major national firms, including Merck, Firestone, Procter & Gamble, M & M Mars, and Miller Brewing, established manufacturing plants. Together with locally owned Bobs Candies, the world’s largest candy-cane maker, they provided thousands of new jobs in Albany. In addition, the U.S. Marine Corps established the Marine Corps Logistics Base, Albany on the east side of town and became the city’s largest single employer. The 1970s, however, saw an economic downturn that began with the closing of the Naval Air Station at Turner Field. Further plant closures in the 1980s contributed to Albany’s rising unemployment—the highest of any metropolitan area in the state for several years. The economic decline eased in the late 1980s, and several major industries established new plants in Albany in the 1990s.

Higher Education

In 1903 African American educator Joseph Winthrop Holley founded the Albany Bible and Manual Training Institute, a private precollegiate school. Eventually the state took over the school and made it a two-year, and eventually a four-year, college. In 1996 it became Albany State University, one of the few historically Black institutions in the University System of Georgia.

In 1961 the Monroe Area Vocational-Technical School was established, which eventually became Albany Technical College.

In 1963 the Board of Regents established Albany Junior College to meet the needs of white residents for higher education close to home. Albany Junior College eventually became Darton College, a two-year institution that was successful in attracting a substantial number of students of color. In 2012 the college became a four-year institution named Darton State College.

Force of the Flint River

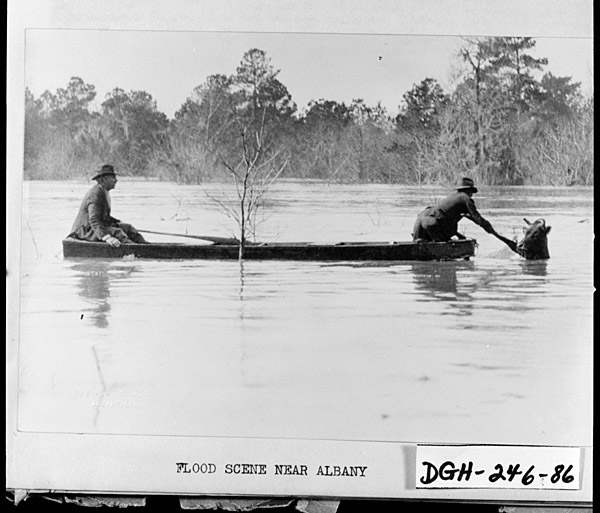

The Flint River has played a major role in Albany’s history. It was the early major link with the outside world, but it soon demonstrated to Albany residents the power of nature. Major floods hit Albany in 1841 and 1925, but no one was prepared for the 500-year flood that devastated southwest Georgia in the summer of 1994. By the time the Flint River crested at more than forty-three feet in Albany, the worst-hit community, twenty-three square miles of Dougherty County were under water, and 23,000 residents had been forced to evacuate. The cost of damage was reckoned in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Out of the tragedy, however, came much good. The state supported the complete $150-million renovation of Albany State University’s flooded campus, turning it into one of the state’s most impressive campuses. Inadequate housing on much of Albany’s south side was torn down and replaced with better structures, improving the quality of life for many living in the river’s flood plain.

Although the river has not been tamed, the city has shown greater respect and appreciation for it. The 1990s saw the beginning of a major downtown renovation with the creation of a Flint River Walk, designed to bring Albanians back to downtown and to the river responsible for the city’s founding. In September 2004 the Flint RiverQuarium, a $30 million freshwater aquarium, opened. The aquarium resembles a “blue hole,” a naturally occurring aquifer spring; such springs are found in southwest Georgia. Exhibitions focus on the natural habitats of the Flint River, and educational displays explain and promote water conservation. The RiverQuarium also includes an Adventure Center exhibition hall, containing an IWERKS screen on which 3-D films are shown.

In December 2007 the Ray Charles Plaza, which commemorates the birth of the musician in Albany, opened along the river.