The Atlanta Colored Music Festival Association, founded by African American Congregational minister Henry Hugh Proctor, presented a concert in 1910 remarkable not only for the quality of its program but also for its audience, Blacks and whites seated separately but under one roof in Atlanta. Subsequent annual concerts continued until about 1918. Proctor’s complex motivation for the concerts had a simple foundation in his conviction that music could ease racial animosity and even promote racial harmony.

The Concerts

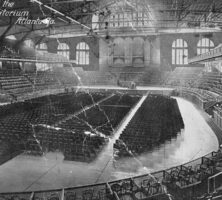

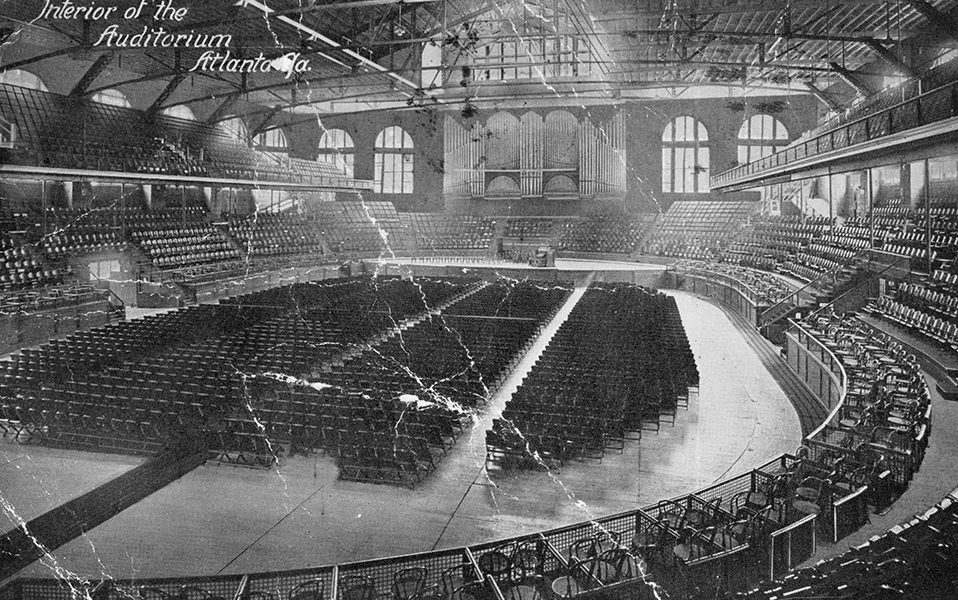

One may safely assume that Atlanta’s temperature was high and the air thick with humidity on August 4, 1910, when the Atlanta Colored Music Festival Association presented its debut concert. The approximately 2,000 people gathered that evening in Atlanta’s Auditorium and Armory (later Atlanta Municipal Auditorium) doubtless waved cardboard fans to create some semblance of a breeze in those days before air-conditioning. Like all southern audiences of that era, the crowd was segregated. Whites sat in a 1,000-seat section “set apart for white patronage.” Atlanta mayor Robert F. Maddox, who had promised to attend, would have been in that special section, enjoying a concert experience rare for him and other whites. The performers were all African Americans.

The program opened with an overture played by three young women pianists and featured a chorus of 135 singers, “detachments” of which had made the rounds, singing in various Black churches “for the purpose of arousing interest in the festival.” The classically trained baritone and star of the evening, Harry T. Burleigh, who had performed concerts in European capitals, presented a selection of German songs. The Fisk Jubilee Singers, of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, sang numbers that the Atlanta Constitution termed “dear to the southland,” though they strike the modern listener as romanticizing the plantation past: “Old Kentucky Home,” “Swanee River,” “Old Black Joe,” and more. Joseph Douglass, a grandson of writer and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, played a violin solo accompanied by his pianist wife, the daughter of Atlanta undertaker D. T. Howard. Pearl Wimberly, a soprano and graduate of Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University), sang two solos. The Constitution noted that she “lately sang before [Italian opera singer Enrico] Caruso while he was in the city, and the latter expressed the highest appreciation of her voice.”

The Constitution article, after advising readers about ticket prices (balcony 25 cents, dress circle 50 cents, pit 75 cents, box seats 1 dollar), explained that proceeds from the concert would fund the institutional work of First Congregational Church, “an organization which has been most effective in uplifting the colored people of this city, morally, physically and mentally.”

More annual concerts followed, reaching a peak of grandeur in 1913, when the festival commemorated “the fiftieth year of the emancipation of the race in the United States.” In 1914 the Atlanta Colored Music Festival Association changed its name to the Georgia Music Festival, and a more modest event was held at First Congregational Church. By 1918 the festival had returned to the Auditorium and Armory for what was likely the association’s final concert.

Ministry of Henry Hugh Proctor

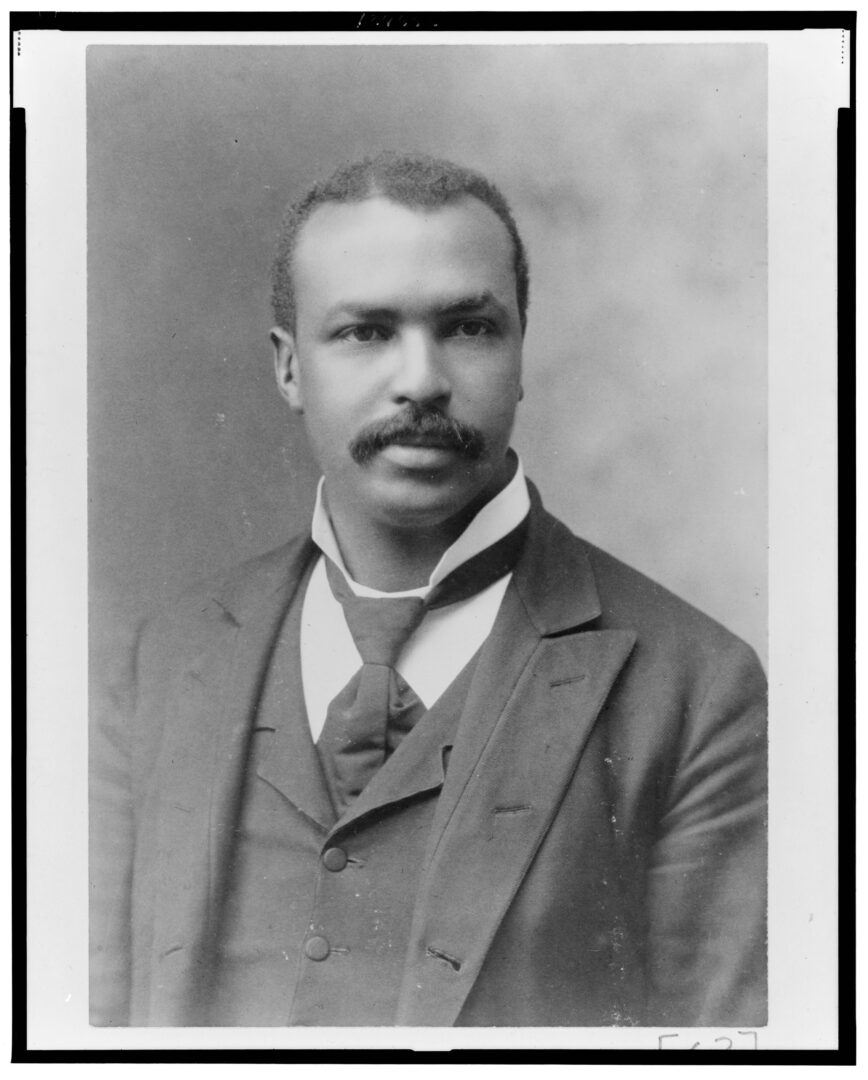

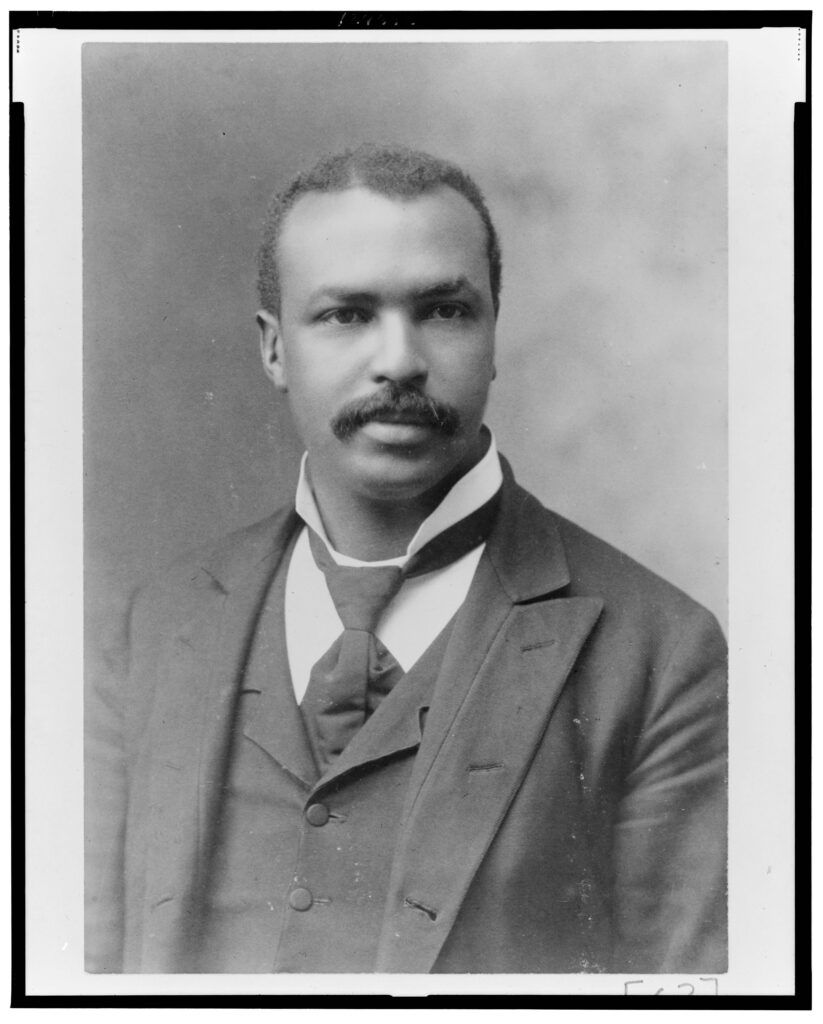

The guiding creative force behind the concerts, Proctor was born in December 1868 in rural Tennessee. After graduating from Fisk University, he earned a Bachelor of Divinity from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Proctor married a Fisk classmate, Adeline Davis, and in 1894 he accepted the pastorate of First Congregational Church in Atlanta. Established in 1867, First Church, as most called it, played an important role in the development of Atlanta and especially its African American community in the decades after the Civil War (1861-65).

Proctor’s energy found many outlets at First Church. With help from the American Missionary Association and from African American educator Booker T. Washington, who approached some of his own supporters for funds, Proctor built a new church edifice in 1908. His numerous neighborhood initiatives included the founding of an orphanage and two prison missions, as well as the installation of a public water fountain. The fountain was not inconsequential. It augmented the only public access to drinking water previously available to Blacks in the community: a horse trough.

The church’s educational efforts during Proctor’s tenure included the establishment of a library, a kindergarten, classes in business education and domestic science, and classes for the blind. First Church also offered a gymnasium, an employment bureau, and a home for young working women.

Origin of the Festival

Soon after the Civil War, Atlanta’s white music devotees began bringing musical performances to the city. By 1901 singers from the New York Metropolitan Opera (Met) were visiting Atlanta, and in 1905 the Atlanta Music Festival Association (AMFA; the descriptive “white” was understood) was formed. In early 1910 AMFA presented the Met performers in six spring performances; this tradition would continue, with occasional interruptions, until 1986. Proctor learned that some of his parishioners had considered donning maids’ uniforms to slip, unremarked, into the Met presentations. Perhaps in response, he organized the Atlanta Colored Music Festival Association in July 1910, only weeks before the first concert took place.

Proctor’s motives were multiple. He was an accomplished singer himself and joked about the jobs he took to pay for his education: “I dug my way through Fisk and sang it through Yale.” He believed in music’s uplifting power, insisting that the parlor of First Church’s young women’s home include a piano. He also saw music as a bridge between the races and perhaps as an extension of his work following the bloody Atlanta race massacre of 1906. That eruption of simmering racial resentment, stirred by a vicious contest for the state governorship, caused two confirmed deaths among whites and the deaths of twenty-five to forty African Americans. In the aftermath of the massacre, Proctor and Charles Hopkins, a white lawyer, recruited forty men—twenty white and twenty Black—to address the city’s racial animosities.

Proctor himself wrote about another motive: he wanted to prove to skeptical whites that his people could achieve cultural sophistication, as demonstrated irrefutably by the performers’ artistic excellence. The Constitution quoted him: “By organizing this music festival we wish to show that there is another class that is eager to follow the good and not bad in striving for the better things of life.” Economics, too, must have been on Proctor’s mind; the concert proceeds funded his church’s ambitious social outreach. The concerts also provided an arguably balanced means of introducing the white community, dominant in numbers and wealth, and perhaps potential supporters, to the proud and productive Black community.

In 1920, two years after the final concert, Proctor left First Congregational Church and moved to the Nazarene Congregational Church in Brooklyn, New York, where he served until his death in 1933.

Legacy

Echoes of Proctor’s successful 1910 concert reverberated in 2001, when the Reverend Dwight Andrews of First Congregational Church and Steven Darsey of Meridian Herald, an Atlanta-based organization advancing worship and music traditions, including The Sacred Harp shape-note music, jointly reprised his efforts through a musical collaboration. Intent on bridging communities and traditions of the past and present, these modern concerts, known as the Atlanta Music Festival, have included The Woman at the Well, a sacred opera by Andrews; folk hymns from the Sacred Harp; spirituals; and African American classical music. The venues for the performances in Atlanta have included First Congregational Church; Glenn Memorial United Methodist Church and the Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts, both at Emory University; and Spelman College.