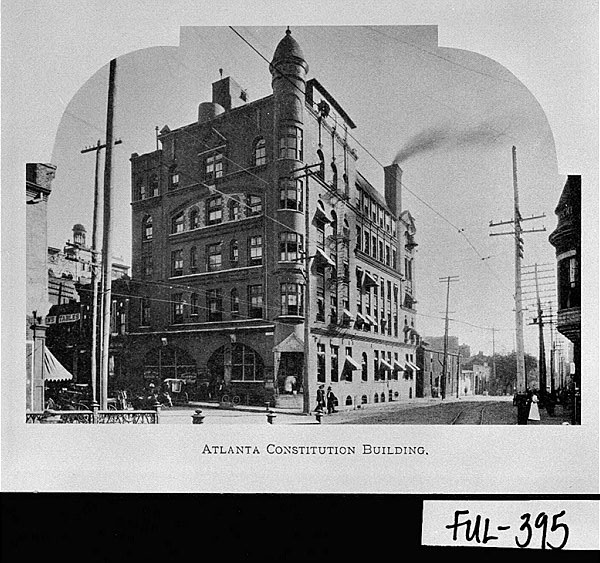

In the late nineteenth century Bill Arp’s weekly column in the Atlanta Constitution, syndicated to hundreds of newspapers, made him the South’s most popular writer. Others surpassed him in literary quality, but in numbers of regular readers, no one exceeded Bill Arp.

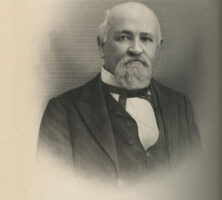

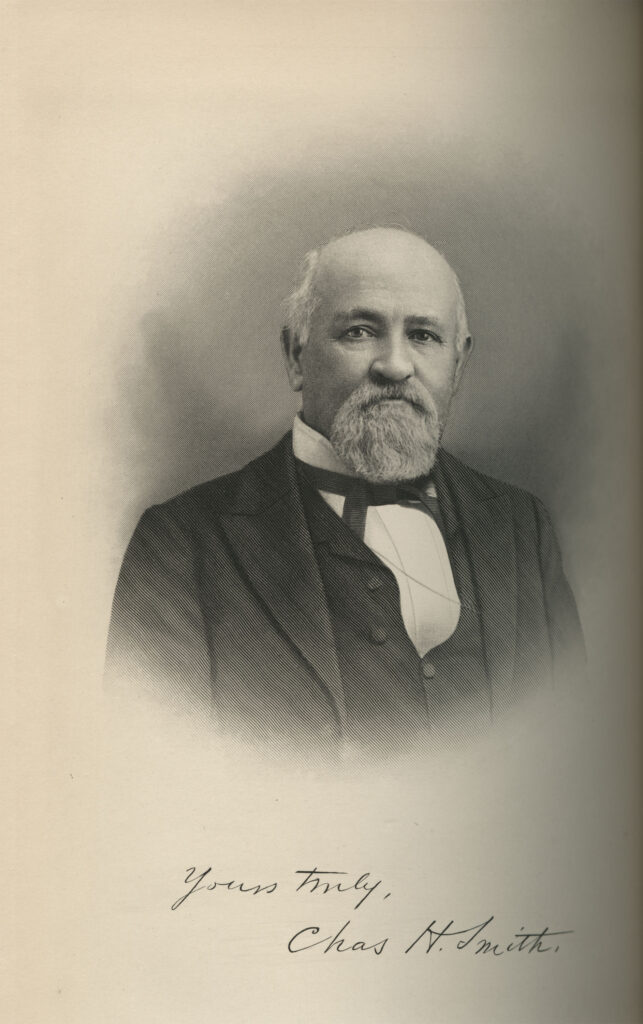

Bill Arp was born Charles Henry Smith in Lawrenceville on June 15, 1826. He married Mary Octavia Hutchins, the daughter of a wealthy lawyer and plantation owner, and started a family that would eventually include ten surviving children. Smith studied law with his father-in-law and then moved to Rome in 1851.

Smith took his famous pen name in April 1861 when, after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, U.S. president Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation ordering the Southern rebels “to disperse and retire peaceably.” Smith wrote a satiric response to the president in the dialect favored by humorists of the day (“I tried my darnd’st yesterday to disperse and retire, but it was no go”) and signed it “Bill Arp,” in honor of a local “cracker” named Bill Arp. The letter to “Mr. Lincoln, Sir” was reprinted across the South and made Bill Arp a household name. During the war Smith wrote almost thirty more Arp letters for southern newspapers, attacking Union policies, praising the Confederacy, and describing in a humorous fashion his family’s experiences as refugees (“runagees,” he called them) while fleeing from advancing Federal troops in 1864. Arp later criticized the nation’s Reconstruction policies in letters that often expressed a good bit of frustration, even anger.The Arp letters ended in the early 1870s, as Reconstruction came to a close in Georgia.

In 1877 Smith and his family moved to a farm in Bartow County, just outside of Cartersville. A year later the Atlanta Constitution printed a new letter from Bill Arp, his first in half a dozen years and the beginning of a twenty-five-year series of weekly columns called “The Country Philosopher.” The letter, on the joys of farming, was in many ways different from the Bill Arp of the war and Reconstruction. Gone was most of the dialect (it would never completely disappear), but more important, the subject matter had changed: Arp now wrote delightful epistles of the pleasures of rural life, the comfort of home and family, the independence and strength of Georgia’s common folk, and the bright memories of the days of his youth. Arp still wrote occasionally on political, economic, and social issues, including a number of pro-lynching columns in the 1890s, but it was his “homely philosophy,” as it was called—his writings on the farm and fireside, the past, and various pastoral topics—that made him so popular.

The message of Arp’s Constitution columns was ambiguous. On one hand he promoted the economic growth of Henry W. Grady’s New South program; on the other hand he criticized many aspects of New South society, and one can read his homely philosophy as implicit criticism of the new age. Perhaps this explains his popularity: he reflected the ambiguous feelings of many other New Southerners.

Smith died on August 24, 1903, and is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Cartersville.