Georgia has a wealth of extant camp-meeting grounds across the state. These historic sites developed as a result of the Second Great Awakening, a series of revivals that occurred from about 1790 to 1830 and planted the values of Protestantism deep in the American character, especially in the South. This religious movement galvanized the entire nation after the American Revolution (1775-83) and by 1820 helped to form the distinct national characteristic of a revivalist society. The Second Great Awakening, often called the Great Revival, became a regional phenomenon in the South, fostering the development of three major denominations, the Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches, and creating what some have called the Bible Belt.

The camp meeting, an outdoor, continuous religious service, became a fixture of Georgia’s religious life. In fact, the meetings were so popular by the 1890s that the phrase “at a Georgia camp meeting” became a trite expression the world over. At least thirty of these sites, reflecting the camp-meeting movement and exhibiting its vernacular architecture, remain active in the state into the twenty-first century.

History

Although Effingham Camp Ground in Springfield claims to have held camp meetings as early as 1799, most scholars believe that meetings did not occur there until after August 1801, when a very large and influential meeting known as Cane Ridge was held in Kentucky. Several camp meetings were held in Georgia during the winter of 1802 and spring of 1803, as interest and enthusiasm spread among the Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian clergy and citizens who attended. A crowd of 3,000 is purported to have attended Georgia’s first “recorded” camp meeting, held in February 1803 on Shoulderbone Creek in Hancock County. For the next several years, camp meetings thrived in Georgia, setting the stage for a revival element that became a customary feature of religion in the state, especially in the Methodist Church.

Although many camp-meeting grounds have become “interdenominational,” most remain affiliated with the Methodist Church. Other denominations represented today are Congregational Holiness, Church of the Nazarene, and Presbyterian. Smyrna Campground in Rockdale County is the only Presbyterian site in the state. Founded in 1831, it is one of the state’s oldest sites and one of only three Presbyterian campgrounds in the nation.

Architecture and Setting

Camp-meeting grounds are distinguished by a particular type of architecture and layout adhering to three general patterns of arrangement: oblong square (rectangular), horseshoe (semicircular), and occasionally circular. The establishment of a church and cemetery was a common physical development pattern at many Georgia sites, and camp-meeting grounds often served as the center for religious activity within a community.

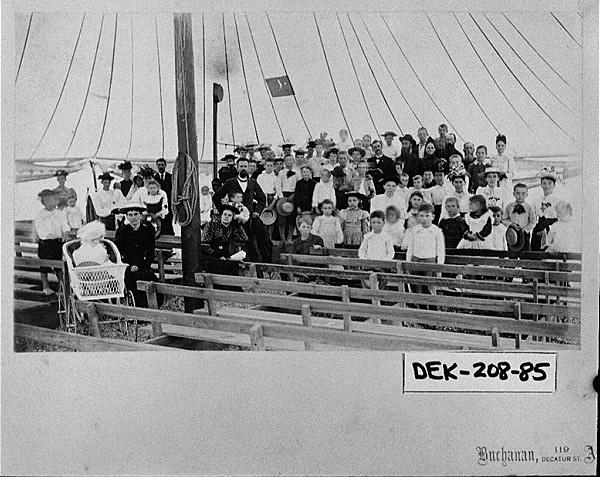

Trees served as the architecture of early camp meetings, with candles and pine-knot torches lighting the evening services and campfires illuminating the worship area. However, once an encampment became established, brush arbors—simple open-air shelters—became common, and by the 1820s, two new building types, arbors and tents, had appeared, especially in the So uth and the Ohio River Valley. Large open tabernacles, or arbors, covered the preachers and worshipers during the services, while permanent wooden cabins known as “tents” housed the attendees during the encampment. Today most meeting grounds are managed by self-perpetuating boards of trustees that own the land, while individual families own the tents, which are often passed down through generations.

Arbors, the most important feature of southern campgrounds, constitute an American building type that is noticeably consistent from Virginia to Texas. As a landmark structure, the arbor was the major organizing feature in the planning of the grounds. Arbors are powerful architectural forms constructed with large square timber supports, angle braces, and exposed trusses topped by massive sheltering roofs, which are usually covered with tin. The roofs are pyramidal, hipped, gabled, or a combination of these, and some roofs feature clerestories for light and ventilation. Many of Georgia’s arbors display hand-hewn timbers and use either pegs or mortise and tenon construction. Most campground arbors are oriented on a north-south axis to avoid the glare of the sun and function like the common public space of a village green or courthouse square.

Camp-meeting tents in Georgia are almost consistently one-story, one-bay wooden buildings with front gable roofs and shed porches, dirt floors covered with sawdust or straw, and partial partitions and screened vents for air circulation. Shed-roofed porches ran along the front of each tent at some sites to encourage community bonding. Examples of this type of construction may be found at Effingham Camp Ground (Effingham County), Lebanon Camp Ground (Hall County), and Tattnall Camp Ground (Tattnall County).

Indian Springs Holiness Camp Meeting (Butts County), the flagship campground for the holiness movement in the South, is unlike any other in Georgia. Established in 1890, the camp is larger than others in the state and laid out like a small town, with 141 cottages. (In contrast most campgrounds have an average of 27 more traditional tents.) The oldest cottage at Indian Springs is believed to have been built in 1896.

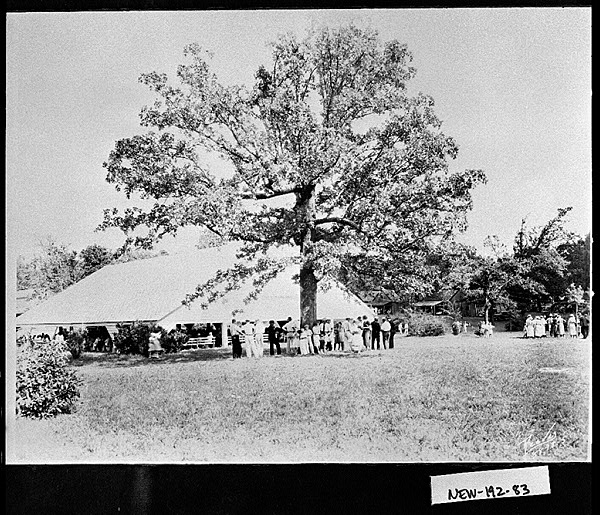

The surrounding landscape is another distinguishing feature of camp-meeting grounds. Given the idea that camp meetings provided a chance for worshipers to commune with God in nature, the topography and other landscape features played a significant role in the selection of the sites. The availability of a water source and the presence of trees, or the “sacred canopy,” often determined the place and name of the retreats. Site names like Fountain, Mossy Creek, Pine Log, Rock Springs, and White Oak indicate the importance of these natural features, while such names as Flat Rock and Pleasant Hill highlight other pleasing landscape features. The founders of Poplar Springs Camp Ground in Franklin County used both water and tree type to name their location in 1832.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

The tradition of painting the trunks of trees encircling the grounds is maintained at Holbrook Camp Ground in Cherokee County and at Lumpkin Camp Ground in Dawson County. An alley of water oaks and laurel oaks leads up an incline to the arbor at Morrison’s Camp Ground in Floyd County.

Existing Sites

One indication of the significance of the camp-meeting movement in Georgia is the relatively large number of extant sites—approximately thirty-five—including a large number of extant antebellum sites located in twenty-seven counties. The greatest concentration (four) is in White County, while two sites each are found in Carroll and Hall counties. Organized by regional development areas, nine are located in the Georgia mountains; six in the Atlanta Region; four each in the Central Savannah River Area, Chattahoochee-Flint Region, and MacIntosh Trail Region; two sites each in the Coosa Valley, Middle Flint, and Northeast Georgia regions; and one each in the Coastal Georgia and Heart of Altamaha regions. The founding dates of these thirty-five active sites range from circa 1820 to 1945, with sixteen encampments established prior to the Civil War (1861-65). Although the date has been disputed, Effingham County Camp Ground in Springfield is believed to be the oldest camp-meeting site in the state, dating from around 1790. Pine Mountain Campground (Pike County), founded in 1945, is the youngest “traditional” camp-meeting ground.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Recent interest in the preservation of historic camp-meeting grounds has resulted in the listing of four Georgia sitesin the National Register of Historic Places. Two are still “active”: Pine Log Methodist Church, Campground, and Cemetery, located in the historic district of Bartow County, was listed in 1988, and Salem Camp Ground in Newton County was listed in 1998. These two sites, dating from 1834 and 1828 respectively, still hold yearly meetings. Union Point Wesleyan Campground, located within a historic district in Greene County, was listed in 1991. And Wesleyan Methodist Campground and Tabernacle (1902-94) in Turner County was listed in 1998. One early site, a precursor to the Great Revival camp meetings, was a brush arbor constructed in 1786 at Cracker’s Neck (later Liberty Church) in Greene County. Today the site is marked by a Georgia Historical Commission plaque.

From a simple religious gathering held in a grove of trees, camp meetings evolved into a religious movement characterized by a distinctive architecture that survives today as part of the state’s built heritage. Despite regional differences in the buildings and, eventually, in the focus of some of the camp-meeting gatherings themselves, these meeting grounds are all physical reminders of a socio-religious phenomenon that is deeply rooted in America’s history, cultural landscape, and vernacular architecture. Camp meetings became an institutionalized feature of Georgia’s religious history and remain a strong component of religious practice in the state today.