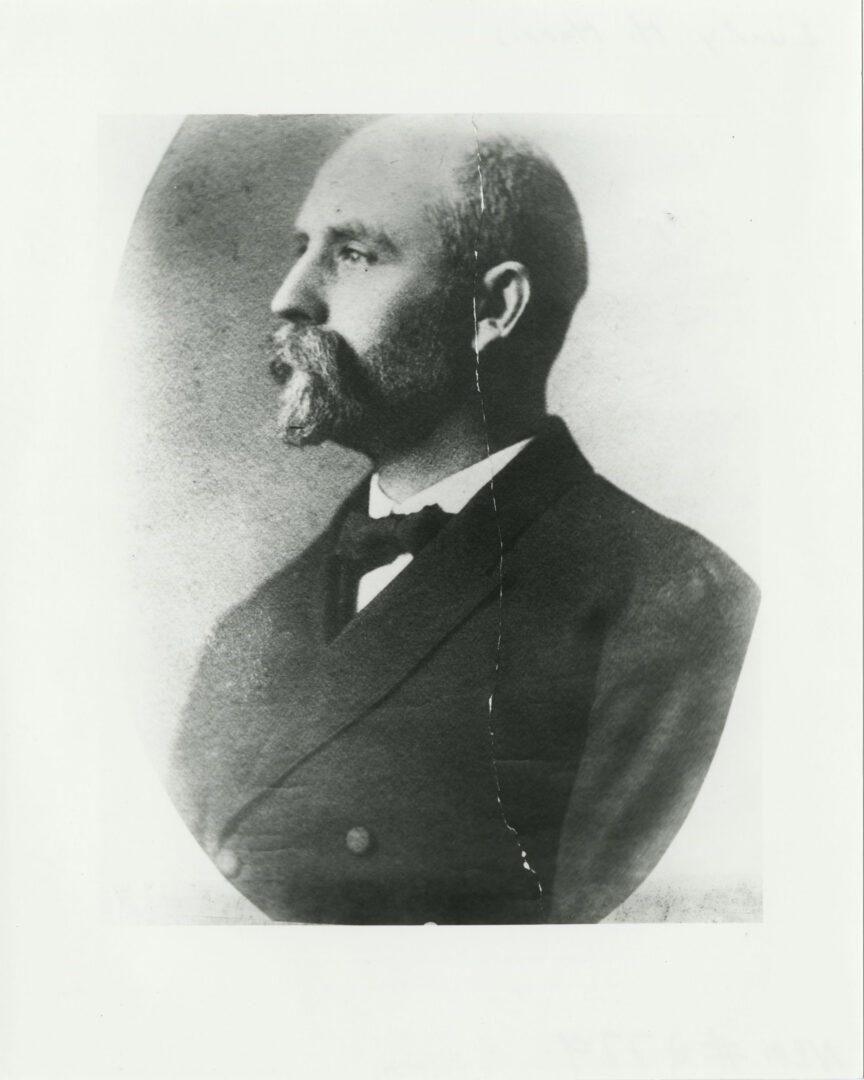

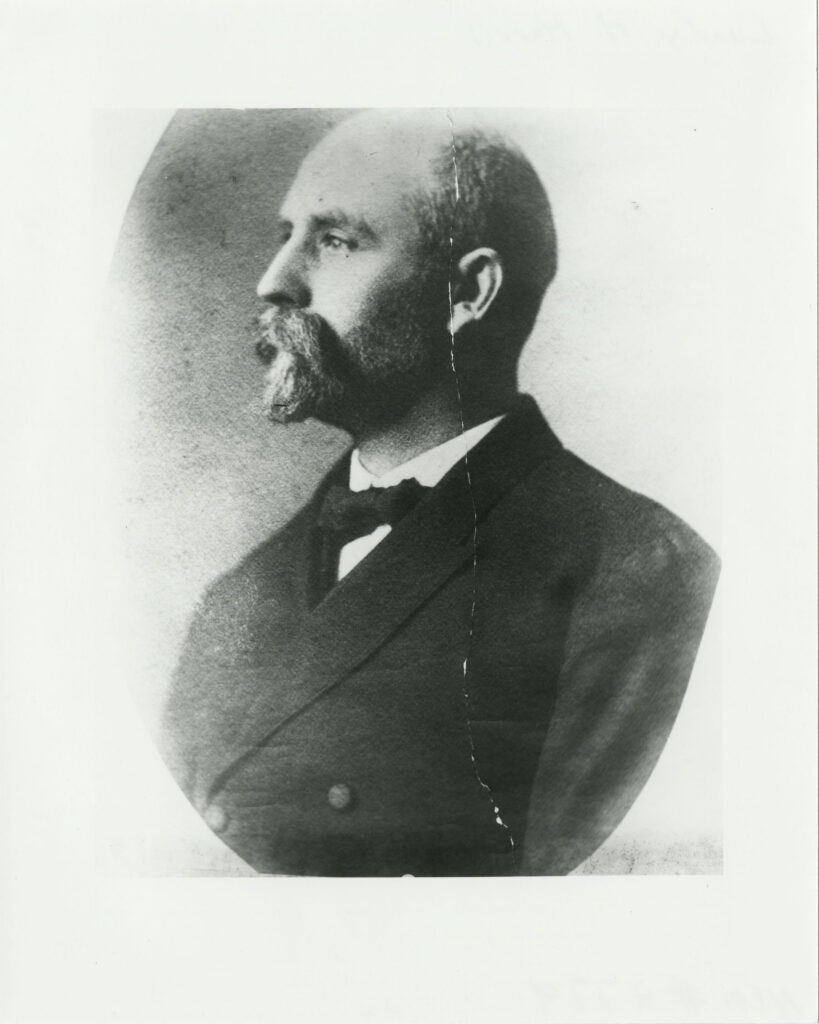

Novelist Corra White Harris was one of the most celebrated women from Georgia for nearly three decades in the early twentieth century.

She is best known for her first novel, A Circuit Rider’s Wife (1910), though she gained a national audience a decade before its publication. From 1899 through the 1920s, she published hundreds of essays and short stories and more than a thousand book reviews in such magazines as the Saturday Evening Post, Harper’s, Good Housekeeping, Ladies Home Journal, and especially the Independent, a highly reputable New York-based periodical known for its political, social, and literary critiques.

Harris established a reputation as a humorist, southern apologist, polemicist, and upholder of premodern agrarian values. At the same time she criticized southern writers who sentimentalized a past that never existed. Most of Harris’s nineteen books were novels, though she also published two autobiographies, a travel journal, and a coauthored book of fictional letters. Two of her works became feature-length movies. Of these, the best known is I’d Climb the Highest Mountain (1951), inspired by A Circuit Rider’s Wife. The film was written and produced by Georgia native Lamar Trotti and starred Susan Hayward and William Lundigan. She was the first female war correspondent to go abroad in World War I (1917-18).

Early Life

Born Corra Mae White on March 17, 1869, on Farmhill Plantation in the foothills of Elbert County, she was the daughter of Tinsley Rucker White and Mary Elizabeth Mathews White. Like many southern women of her day, she did not have an extensive education. She attended Elberton Female Academy but never graduated and, as a writer, was largely self-taught. In 1887 she married Methodist minister and educator Lundy Howard Harris. They had three children, only one of whom—a daughter named Faith—lived beyond infancy.

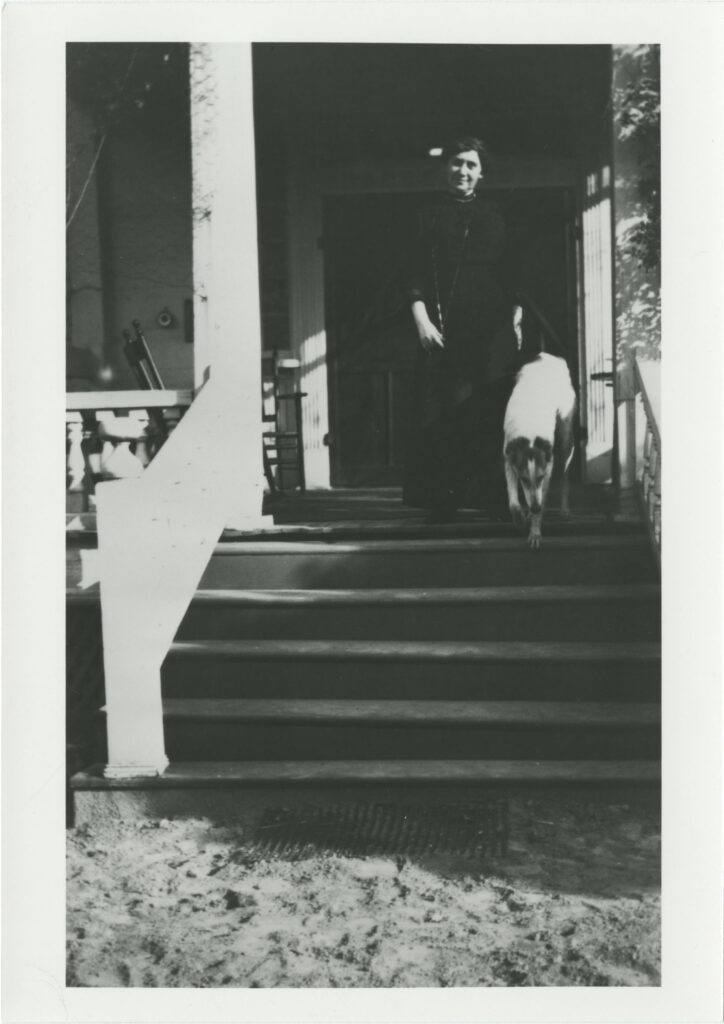

Harris’s career developed out of financial necessity. Her husband’s life in the Methodist ministry and in ministerial education was punctuated by incapacities from bouts of alcoholism and depression. Before and after Lundy Harris’s death in 1910, Corra Harris assumed responsibility for her immediate and extended family’s financial survival. She remained a widow, spending the last two decades of her life at the place she named “In the Valley” just outside Cartersville in Bartow County. There she died in 1935, having outlived her daughter by sixteen years.

Career

Harris’s prolific writing career began in 1899 with an impassioned letter to the editor of the Independent. William Hayes Ward wrote a searing editorial about the lynching in Georgia on April 23, 1899, of Sam Hose, a Black man accused of killing a white farmer and raping his wife. Harris replied with a conventional defense of lynching, yet she so impressed the editors with her disarming expression of homespun politics that the Independent encouraged further submissions.

Of all Harris’s works, the most acclaimed was A Circuit Rider’s Wife, the first of a trilogy in the Circuit Rider series. A Circuit Rider’s Widow (1916) and My Son (1921) followed. Semiautobiographical, A Circuit Rider’s Wife is the story of itinerant Methodist minister William Thompson and his wife, Mary, and their life together on a church circuit in the north Georgia mountains. The novel received much attention when first published because Harris alleged that itinerants and their families suffered needless hardships from the unfair distribution of resources to urban clerics. The book has been noted since that time for its portrayal of rural mountain folk in their earthiness and simplicity. It was reprinted in 1998 by the University of Georgia Press.

Less well known, though not less relevant for its social critique, is The Recording Angel (1912). This novel, set in a little town called Ruckersville in the hills of north Georgia, depicts a place where residents are so devoted to the legacy of their Confederate heroes that they have isolated themselves and become culturally barren. Harris mocks the Lost Cause mythology, and again she reveals the excesses and limitations of evangelical religion. This book, along with Harris’s first novel, reflects her efforts to come to terms with modernity.

One of her works, The Co-Citizens (1915), illustrates especially well the paradoxical nature of Harris’s personality and politics. The protagonist is loosely based on Rebecca Latimer Felton, a fellow Georgian, and Harris purportedly wrote the novel to illustrate support for the woman suffrage movement, though she was actually more ambivalent about than supportive of the movement. Although many (including Felton) accepted The Co-Citizens as a pro-suffrage statement, others read it as a barely veiled attack on feminism, a way of life Harris lived in practice yet rejected in theory.

Harris’s two autobiographies were quite acclaimed in their day. My Book and Heart (1924) was more popular with the public, though Harris felt that As a Woman Thinks (1925) was her best and most satisfying work. During the 1930s her publishing career was largely limited to the locally popular “Candlelit Column,” a tri-weekly article in the Atlanta Journal. Harris died of heart-related illness on February 7, 1935.

In 1996 Harris was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement.