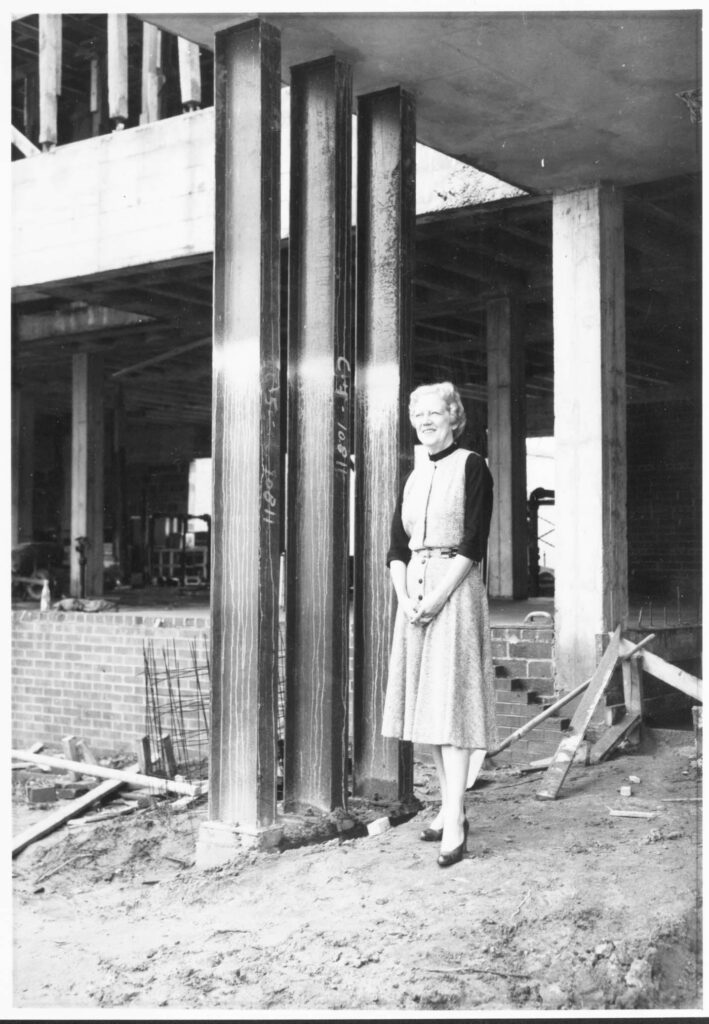

Ellamae Ellis League practiced as an architect in Macon for more than fifty years, from 1922 until she retired in 1975. She was a pioneering woman in the architectural profession in the South. League ran her own successful practice for forty-one years (1934-75). Her work spanned the whole range of architectural design—new homes, residential remodeling, churches, schools, public housing, office buildings, parking garages, hospitals, and even a residential bomb shelter. League was elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects (FAIA) in 1968. At the time of her death on March 4, 1991, League was still the only female member of the FAIA in Georgia, and one of only eight nationwide.

The fourth child of Susan Dilworth Choate and Joseph Oliver Ellis, Ellamae Ellis was born in Macon on July 9, 1899. She and her three brothers attended public schools in Macon. After graduating from Lanier High School in 1916, she briefly attended Wesleyan College. On June 27, 1917, she married George Forrest League.

League became an architect by necessity. In 1922, divorced at age twenty-three with two small children, she entered a profession for which she had no training. Her husband of five years had left her with no financial resources, and she needed to find employment. Six generations of her family, including an uncle in Atlanta, had been architects. She joined a Macon firm as an apprentice and remained there for the next six years, as she managed both office and child-rearing duties. During that time League also took correspondence courses from the Beaux Arts Institute of Design in NewYork City.

Courtesy of Middle Georgia Archives, Washington Memorial Library.

Inspired by her experience with the Beaux-Arts method of architectural training, League left her children with their grandparents and quit her job, a decision she later called “very difficult.” She studied for a year (1927-28) at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Fontainebleau, France. After her return, League worked for other Macon architects until 1933. Once she earned her professional registration as an architect in 1934, she opened a practice under her own name. Commissions during her first year as a registered architect included a service station, six residences (including a log house), a reservoir, two church buildings, and a residential restoration. Refusing to seek special consideration as a woman, she stated, “If you are an architect, you are an architect.” A major project that she undertook toward the end of her career, in 1968-70, was the restoration of the Grand Opera House in Macon. League closed her practice in 1975 at the age of seventy-six.

Courtesy of Middle Georgia Archives, Washington Memorial Library.

In 1934 only 2 percent of American architects were women, and women who were principals in their own firms were practically nonexistent. Most women architects specialized almost exclusively in domestic architecture—they were considered to have a better “feel” for house design. League, in contrast, took on a variety of jobs, including Public Works Administration commissions. She designed many churches, schools, and hospitals, which were her favorite projects because they were so complex, and because they were buildings in which people were helped. Her firm did not attempt to establish its own distinctive design style but followed the Ecole des Beaux-Arts philosophy that buildings should fulfill the functional requirements of the owner and be aesthetically pleasing both to the owner and to the public.

Image from Mark Strozier