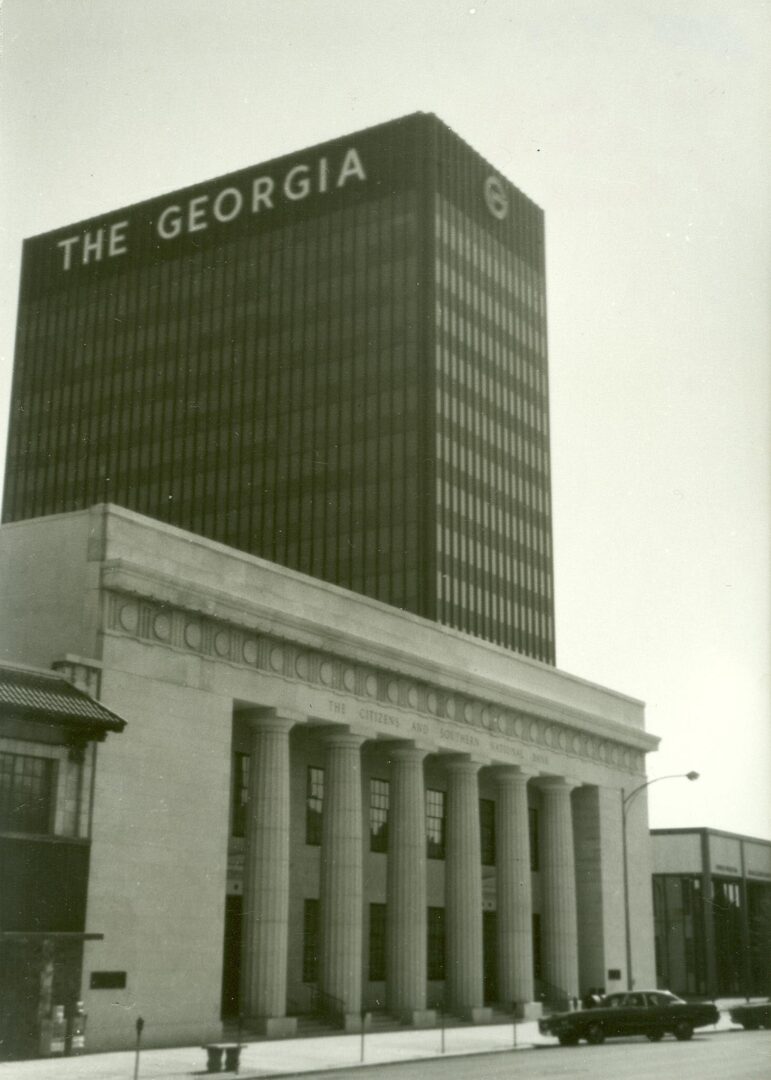

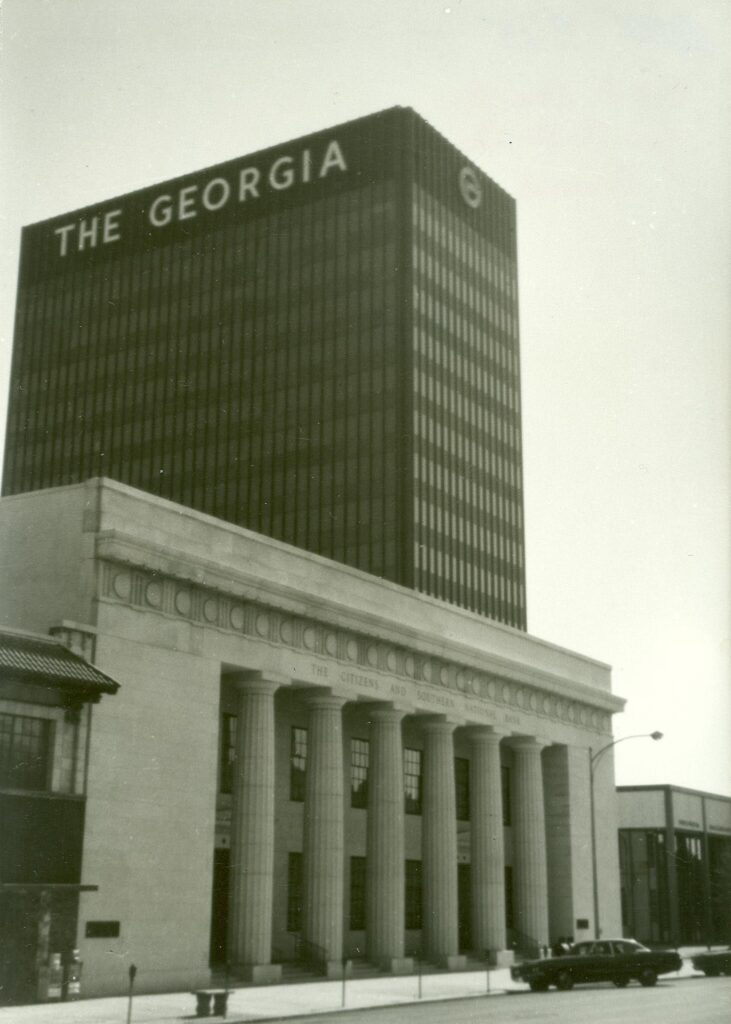

Architecture in Georgia during the last four decades of the twentieth century evidenced a continuing interest in traditional forms for much residential architecture, while the state’s architects built modern workplaces in the latest contemporary styles. This interaction between the conservative attitudes expressing lingering Old South values and the progressive viewpoints promoting the latest image of contemporary styling and newly published architectural forms resulted in a split between the “classicists” and “moderns” in Georgia.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia.

Moderns versus Classicists and Historic Preservation

The battle lines that emerged when modern development accosted traditional neighborhoods and historic districts gave rise to the historic preservation movement. The new architecture, according to the classicists, brought about a numbing of sensibilities with regard to traditional design values and issues of compatibility. Concerned that the computer age was creating architects unable to draw with a pencil, traditionalists quoted designer and critic William Morris’s warning that first the skills would be lost and then the capacity to tell the difference would be lost as well. The moderns, on the other hand, simply argued that technology provided new and more efficient instruments for design, that beauty was being redefined and was not married to historic forms and ornament, and that each generation should design on its own terms, rather than regurgitate the past.

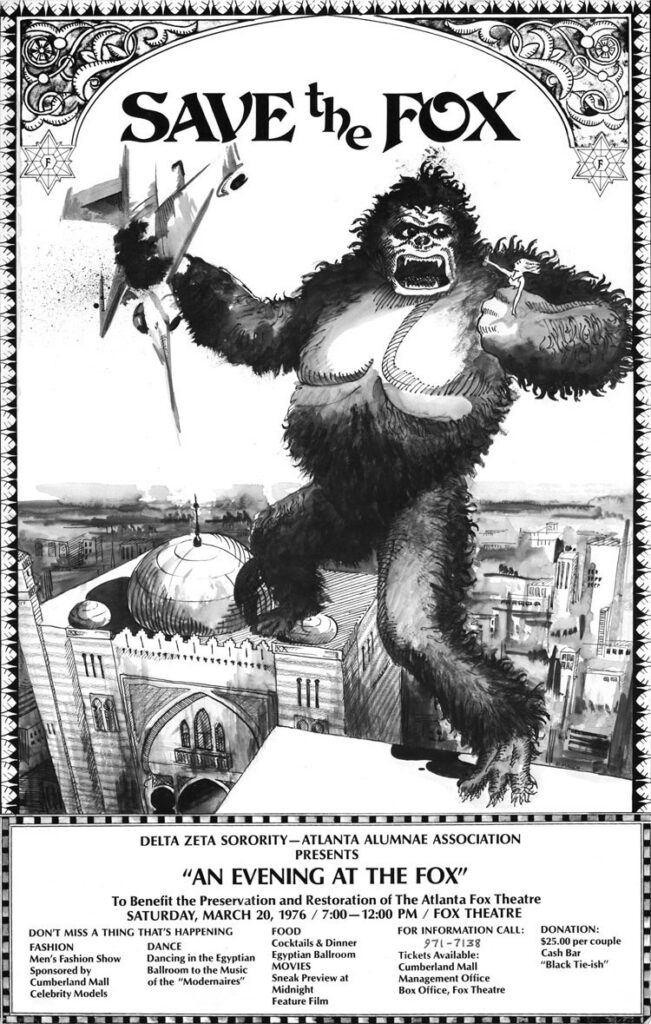

In Atlanta these confrontations included widespread efforts to “Save the Fox,” “Stop the Road,” and “Save the Hunk of Junk,” with the result that a national landmark, the Fox Theatre, was not demolished in the 1970s; the Druid Hills Historic District, a Frederick Law Olmsted landscape park and neighborhood, was saved in the late 1970s; and a prominent local residence nicknamed the “Castle” was preserved in 1990, despite the mayor’s dismissal of the historic landmark as a “hunk of junk.” But development and tendencies to transform in-town Atlanta to a city of steel and shiny glass produced widespread and frequent confrontation because of a sharp reduction in the numbers of properties and neighborhoods protected by new preservation ordinances, as well as an increasing conservative resistance to giving the laws much “teeth.”

Courtesy of Fox Theatre. Copyright Delta Zeta Sorority

Early on, in Savannah, the modern-historic debate reared its head as the Victorian DeSoto Hotel was, regrettably, displaced by Richard Aeck’s almost Brutalist DeSoto Hilton (1966-68). On the other hand, “Main Street” programs, tax credits, grants, and preservation incentives have had remarkable success throughout Georgia, demonstrating time after time the economic benefit of historic preservation.

In some cases, prevailing attitudes in the first half of the twentieth century experienced a complete turnaround during the second half. The “Beautify Main Street” movement of the 1940s, for example, began a modernization of business facades in urban downtowns, often resulting in the covering of remarkable stone- or brickwork of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with artdeco–like Vitrolite, 1950s aluminum screens, or 1960s “environmental” wood or shingle skins.

Subsequent Main Street programs of the late twentieth century removed such modern face-lifts, restoring historic elevations and often rejuvenating central business districts. Small towns in Georgia were often more successful than Atlanta has been in restoring downtown business districts. As preservationists and developers continue to debate the fate of the historic commercial streetscape of Auburn Avenue, Atlanta is again facing the same challenge that towns around Georgia have already addressed. Indeed, since the 1960s, Atlanta has borne witness to urban renewal, rampant suburbanization, the rise of exurbia, sprawl, and the response of New Urbanism. The city is a laboratory, in which such issues are tested daily.

Traditional Architecture and the New Urbanism

All the while, traditional architects continued with what the architectural writer William R. Mitchell calls the Georgia School of Classicists. W. Frank McCall Jr., working out of Moultrie, designed neo-Georgian, southern colonial revival, and other traditionally styled homes statewide for a clientele whose definitions of beauty and elegance were embodied in historic models. In Atlanta, Henry Howard Smith continued the traditions of his father, Francis Palmer Smith, in restoring churches (including the fire-damaged Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, 1982-84), providing sensitive additions to other churches (as evidenced in the cloister arcade at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, 1994-95), and designing appropriate new work (not always continued as sensitively by others) at the Cathedral of St. Philip.

Image from Warren LeMay

James Means carried the torch first lighted by Neel Reid and held high by Philip Trammell Shutze in designing Georgian revival, colonial revival, and occasional continental-styled houses. Means’s residence for Thomas E. Martin Jr. (1965-66) in northwest Atlanta appears to be transplanted from the James River plantation culture of Virginia. His preservation and restoration work at Stone Mountain Park set high standards, and his example inspired both restoration architects and such traditional designers as Norman Askins, W. Lane Greene, and Gene Surber. The principles espoused by Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, as well as the New Urbanists (evidenced in the development at Seaside, Florida, for example), were reflected in the town square of Riverside by Post in north Atlanta (Smallwood, Reynolds, Stewart, Stewart and Associates, and Niles Bolton Associates, 1995-98) and later in the Duluth Town Green (Sizemore Group), in Gwinnett County, and in the Smyrna Market Village (Sizemore Group), in Cobb County. This influence is successfully felt in more pedestrian-friendly development and compatible new commercial and residential infill projects in Atlanta, as seen at Tenth Street and Piedmont Avenue and near Piedmont Park, where the Wilburn House Condominiums (Surber, Barber, Choate, and Hertlein, 2003) is an exemplary project.

Modern Architecture Evolves

Modern architecture in Georgia during the second half of the twentieth century reflected changing styles and new approaches to design, transforming itself decade by decade in much the same way as did modern architecture during the first half of the century, when architecture reflected various schools of the day: art deco, cubism, expressionism, functionalism, futurism, and streamlined moderne, to name a few. For the post–World War II (1941-45) period, the stylistic developments were characterized as Miesian, New Formalist, New Brutalist, postmodern, and New Urbanist, among others.

The Miesian Aesthetic

Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus and the International style became universally reflected in the modern as part of the emerging modernism aesthetic. Equally interested in expressing the new technology and new materials of modern life was Gropius’s compatriot, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was living in Chicago, Illinois, by the 1940s. The steel-frame and glass-curtain wall he promoted was adopted by corporate America during the late 1940s and 1950s, and the Miesian aesthetic emerged as the dominant style for office buildings and commercial architecture of its day. I. M. Pei’s first executed building, the Gulf Oil Building (1949) in Atlanta, displays a well-observed Miesian character. The Fulton National Bank Building (later the Bank South Building; Wyatt Hedrick, with Wilner and Millkey, 1958) at Five Points in Atlanta closes the other end of the 1950s, a decade marked by sometimes green-tinted glass, curtain-wall construction, and a direct expression of frame influenced by Mies’s Chicago work. The black frame that Mies popularized found a more expressive form in the work of New York’s Skidmore Owings and Merrill, evidenced in the John Hancock Center (1969) in Chicago and its contemporary structure, the thirty-five-story Equitable Building (1968) in Atlanta, built in conjunction with Atlanta-based FABRAP.

Courtesy of Augusta Richmond County Historical Society

The seventeen-story Georgia Railroad Bank Building (later Wells Fargo Building) in Augusta by Robert McCreary dates from 1967 and is Georgia’s most Miesian office slab outside Atlanta. At the smaller scale of local branch banks and a few commercial storefronts, full facades of plate glass and the delicate exposed lines of steel structural elements reflect Mies’s dominant influence during the 1950s.

New Formalism

A tendency in the late 1950s and 1960s to style the framing elements of modern buildings prompted temple-like pseudoclassical forms reflective of the New Formalism. Representative examples in Georgia include the Atlanta Civic Center (Robert and Company, 1968), Citizen’s Federal Savings and Loan (later Citizen’s First Bank; William F. Cann, 1974) in Rome, and the Muscogee County Courthouse (Edward W. Neal, 1970) in Columbus. Designs by Philip Johnson and Edward Durrell Stone provided models, and once the volumetric architecture of Gropius and Mies was “formalized,” the door was open to ornament, styling, and the mannered reshaping of a building or its parts, including the display of a more receptive attitude toward borrowed forms from history. Molded and flaring free-form shapes, aluminum grilles, and concrete pierced screens became popular, as evidenced in the thin-shell concrete entry canopies of the Convention Center on Jekyll Island and the pierced block facades, popularized by Stone, of the nearby Buccaneer Beach Resort, both circa 1960s.

Courtesy of Don Bowman

A jet-age plasticity of form streamlined the arcades of Robert and Company’s Atlanta Hartsfield Airport Terminal (1961, razed); energized the open arches of a local bank in Sylvester, seemingly inspired by the futuristic designs found in the 1960s cartoon The Jetsons (circa 1961, also razed); and gave expressionist flare to a hovering, inverted umbrella of thin concrete atop a gas station, a gem of popular culture by architect Dimitri Polychrone that once adorned Lenox Square Mall in Atlanta.

In tall buildings, precast concrete panels brought a formalist style to John Portman’s early buildings at Peachtree Center in Atlanta, although the state’s masterpiece in the style is Atlanta’s Life of Georgia Tower (later One Georgia Center; Lamberson, Plunkett, Shirley, and Woodall, 1967-68). The more conservative articulation of basic constructional form is evident in the office towers of Colony Square (circa 1970) in Atlanta’s Midtown, whose date suggests that this was the moment in Georgia for New Formalism.

New Brutalism

Although most of Colony Square is formalist in style, the exposed concrete surfaces of the apartment/condominium slab behind the office towers (known today as Colony House and Hanover House) show the influence of Brutalism. The best Brutalist building in Georgia, however, is Emory University’s Chemistry Building (Robert and Company, 1969-74). The west wing of the architecture building at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Cooper Carry, 1976-79) is also notable, both for its rough, chipped concrete skin, employed inside and out; its sculptural, raw concrete exterior staircases inspired by Le Corbusier; and its exposed heat and air-duct work, which in true Brutalist tradition is gutsy and unrefined. New Brutalism drew inspiration from elements in several of Le Corbusier’s later works in France—his beton brut (raw concrete) at the Unité d’habitation in Marseilles, his oozing mortar and rough brick at the Maisons Jaoul in Paris, and his plastic expressionism at Notre Dame du Ronchamp.

Photograph by Aria Ritz Finkelstein

The raw materiality of these projects encouraged architects around the world, from Tokyo, Japan, to the United States, to build dramatic “brutal” forms of “as found” concrete, displaying the imprint of form work and the imperfections of a runny fluid substance that was inelegant and earthy—in all a glorification of ugliness 100 years after that of British architect William Butterfield. Proponents described the aesthetic as honest; detractors claimed that the style epitomized a civil-defense-bunker aesthetic and civil rights–era urban panic that turned its back on the city while creating urban renewal nightmares.

A number of Georgia’s public schools constructed during the Brutalist period resemble prisons, although the windowless, inward-oriented Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School (Heery and Heery, 1969-73) in Atlanta garnered professional awards for its architect. As an early attempt at nonstructured classrooms during the 1960s, the school had the added benefit of providing the neighborhood a Brutalist, graffiti-proofed fortress against the social unrest of the period. Nonetheless, Hall and Norris may take the prize for confrontational Brutalism in public school architecture with their Sammye E. Coan Middle School (1967) in Atlanta, the first middle school in the state. Allain and Associates’ Georgia-Hill Street Neighborhood Facility (1975) is another strong contender for non-ingratiating architecture.

Postmodern to New Urbanism

If the public was slow to respond to the intellectual arguments defending a modern architecture they found abrasive, boring, kitschy, or brutal, and if unsuccessful urban renewal projects encouraged a rejection of design styles linked to that modernism, then a late 1960s to early 1970s “postmodern” reaction ensued, led by a younger generation of architects. They included, most notably, Michael Graves, whose works in Georgia include the 1984 renovation of Emory University’s Lamar School of Law Building into the Michael C. Carlos Hall, which today houses the Michael C. Carlos Museum of Art and the History of Art Department; the Ten Peachtree Place office block (1990); and the Egyptoid Michael C. Carlos Museum addition (1995). An underlying classicism informs Graves’s work, which was stylized to become a personal language, as was the work of Edwin Lutyens or John Soane generations earlier in England.

Image from Gary Todd

Postmodern architects rediscovered history, and a New Classicism especially embodied the new attitudes. But postmodernism also brought a more general concern for context, or a willingness to reference place and culture and region, as well as a renewed interest in ornament. Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) and other writings were influential and encouraged architects to reconsider the richness of historic language, the vernacular, and popular culture. Postmodernism encouraged a more eloquent, meaningful, and sometimes witty architecture, and it created a fertile soil from which New Urbanist ideas could later thrive. Although New Urbanist principles inform the Market Square of Smyrna and Duluth Town Green, both by the Sizemore Group, one of the best reflections of New Urbanism in Georgia is Glenwood Park in east Atlanta, a community noted for its commitment to traditional neighborhood design, pedestrian-friendly spaces, and environmental management practices. The community was recognized in 2003 with a Charter Award by the Congress for the New Urbanism.

Iconic Landmarks and International Architects

Architecture displayed a wide range of styles and design approaches during the second half of the twentieth century, and any selection of buildings likely indicates, if nothing else, the pluralism of the period. Francis Palmer Smith’s last work, St. Philips Cathedral (Ayers and Godwin, Associated Architects, 1960-62), is a Gothic revival masterpiece that rivals the best church architecture in the South; the edifice is powerful in form, yet traditional, and built during the very period when Brutalism sought formal substance and strength in raw concrete. Paul Rudolph synthesized both these spirits in his remarkable Cannon Chapel at Emory (1979-81; named for William Ragsdale Cannon), arguably Byzantine in the austere spirit of the Cistercian Romanesque, yet right for Emory’s quad and unmistakably modern.

More natural in its wood and stone materials and textures is Covenant Presbyterian Church in Albany (Pietro Belluschi, 1967-72), a little-known but remarkable church. Such national architects as Graves, Belluschi, and Rudolph were drawn to Georgia and in turn influenced local architects. For example, the High Museum of Art (Richard Meier, 1980-83) inspired a continuing white modernism and elegance of detail in the work of Atlanta architect Anthony Ames, as the Hulse House (1983-86) in Ansley Park gives evidence. Renzo Piano’s new addition to the High, unveiled in late 2005, gives Atlanta another masterpiece. The museum’s exhibition space is as quietly remarkable, sensual, and masterful in the handling of light as is Piano’s Beyeler Foundation (1997) in Riehen (a suburb of Basel, Switzerland). Moshe Safdie’s Jepson Center at Telfair Museums in Savannah displays the work of another internationally acclaimed architect brought to Georgia for a museum addition.