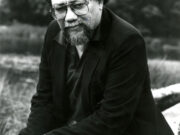

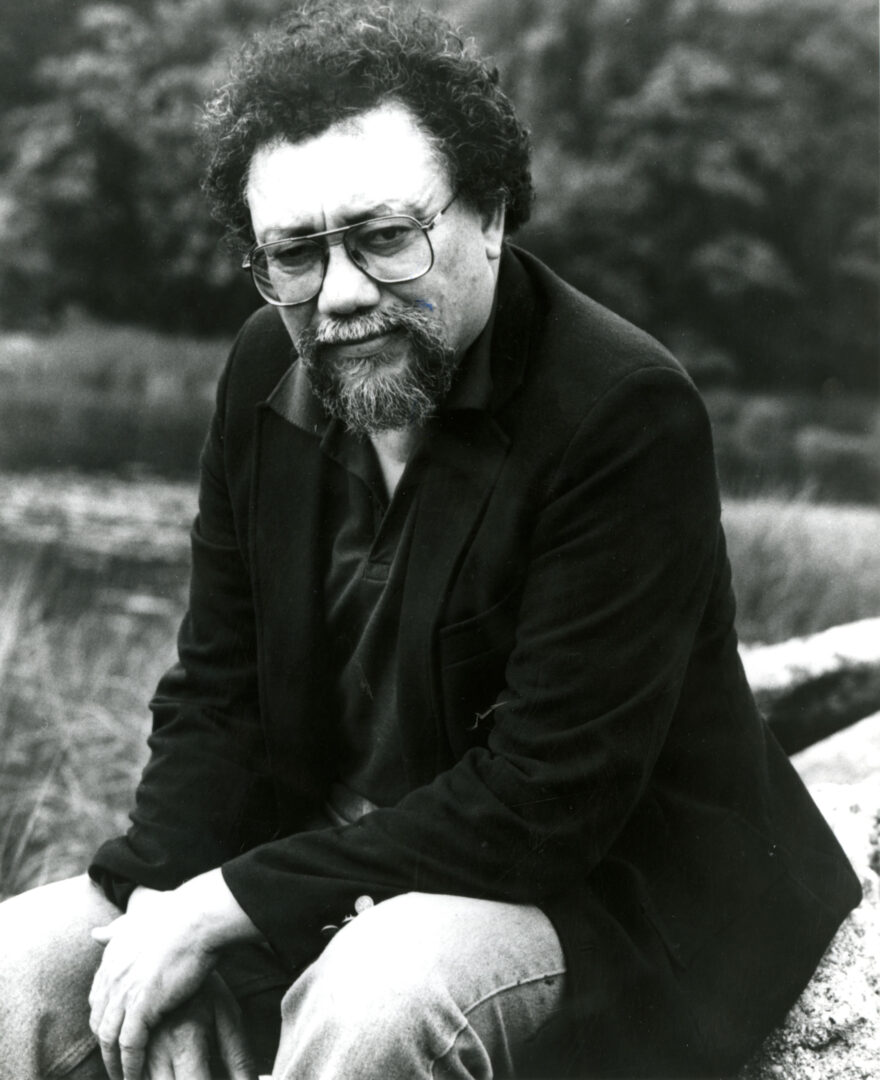

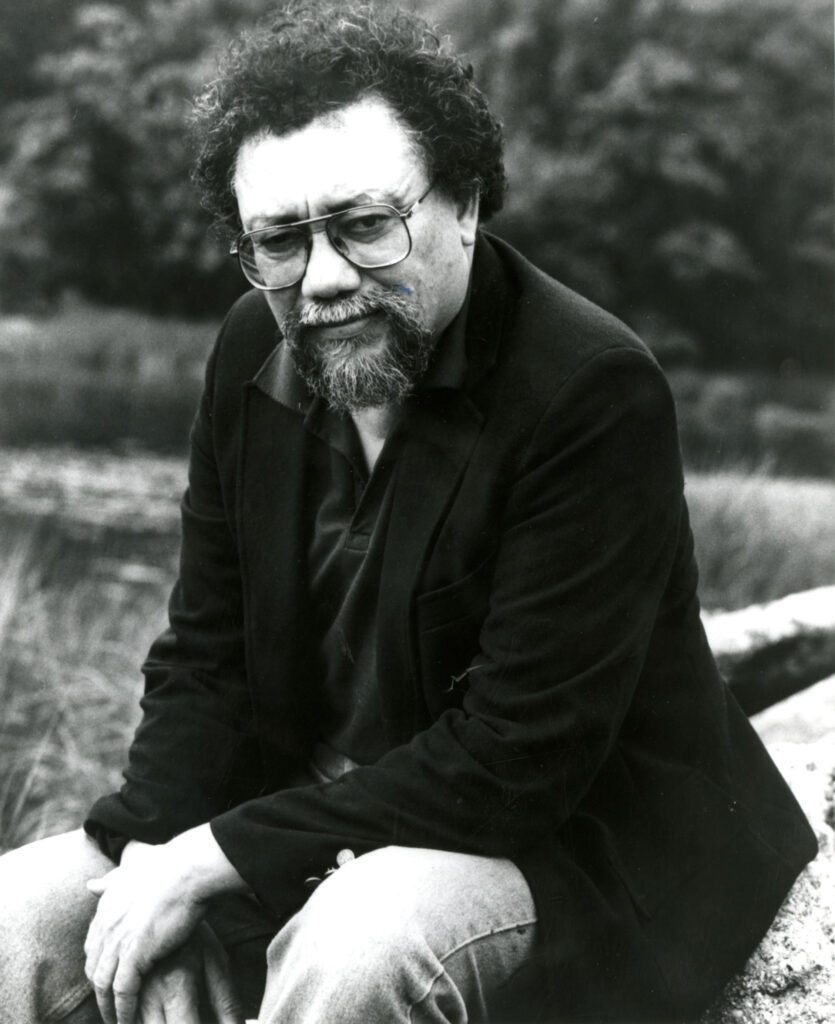

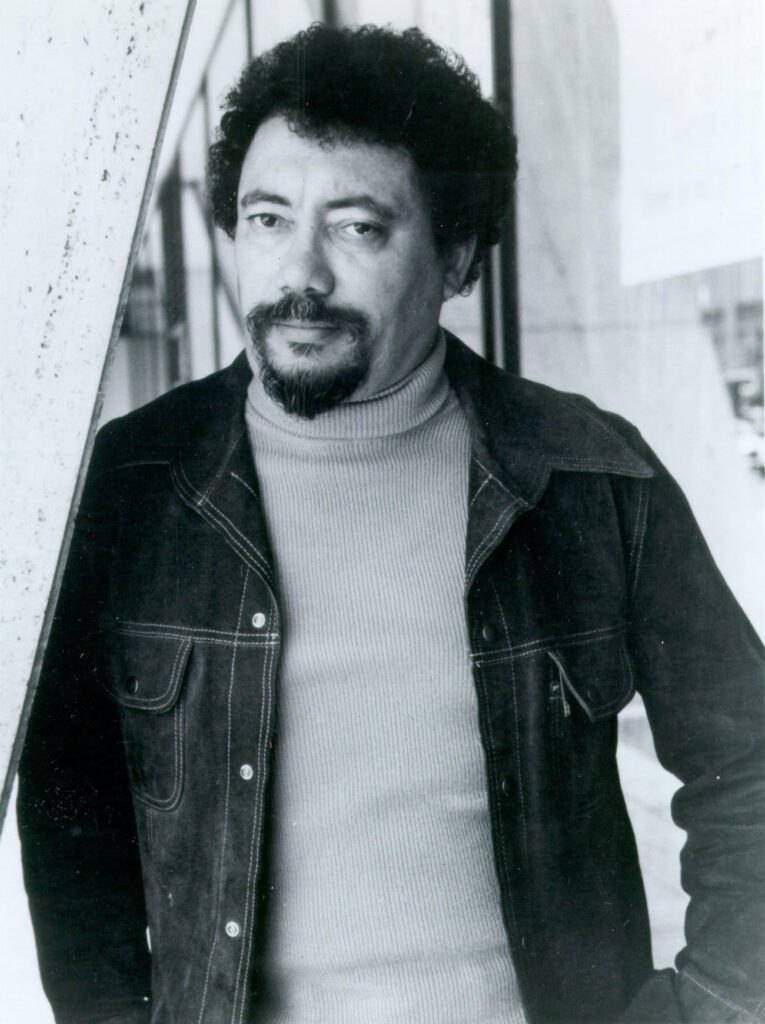

Raymond Andrews was a widely acclaimed novelist and chronicler of the African American experience in north central Georgia. His first novel, Appalachee Red, won the James Baldwin Prize for fiction in 1979. In 2009 he was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame.

The fourth of ten children of sharecropping parents, Andrews was born and reared near Madison. At fifteen he left home for Atlanta, where he worked during the day and attended night classes at Booker T. Washington High School. After graduating from high school he served four years in the U.S. Air Force, including a tour of duty in Korea. On returning he attended Michigan State University and then moved to New York City, where he lived from 1958 until 1984. While there he married, and worked as an airline agent, air courier, and proofreader, among other jobs. His marriage ended in divorce in 1980.

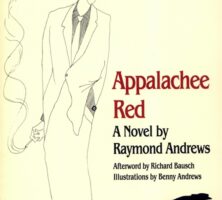

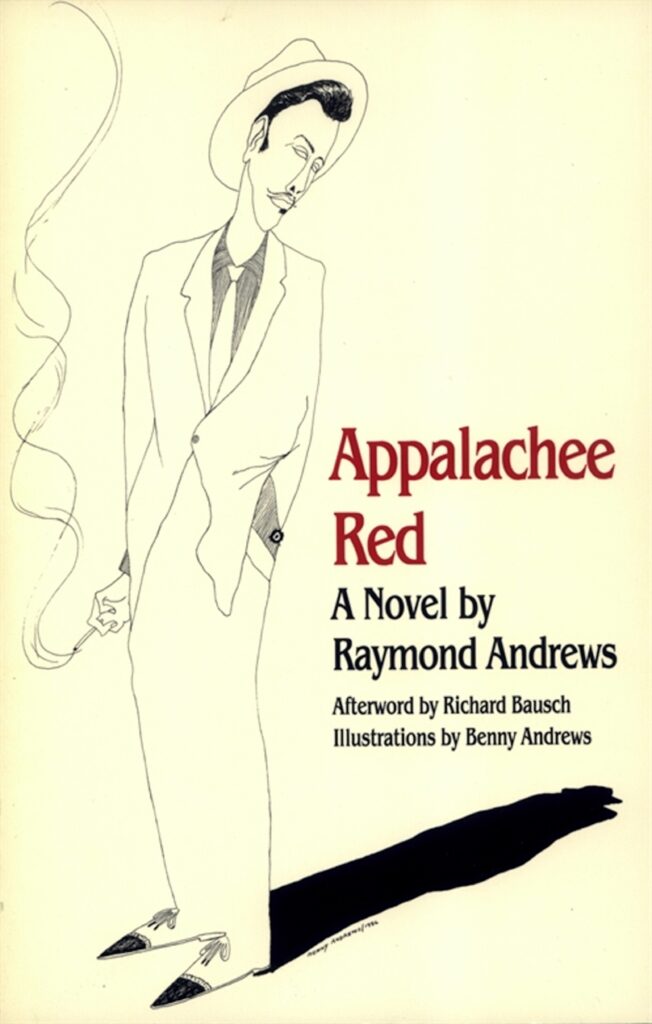

Andrews’s first national publication was a description in Sports Illustrated of the first time the game of football was played in the rural community of Plainview, where he grew up. In the late 1970s Dial Press began publishing his Muskhogean trilogy, which tells of Black life in the Deep South from the end of World War I (1917-18) to the beginning of the 1960s, from the days of mules and white men with bullwhips to the moment the civil rights tide began to change the Georgia Piedmont. The trilogy includes three novels: Appalachee Red (1978), Rosiebelle Lee Wildcat Tennessee (1980), and Baby Sweet’s (1983). Appalachee Red tells the story of a large, red-skinned Black man who changes everything for African Americans in the small town of Appalachee, which is based on the town of Madison. Rosiebelle Lee Wildcat Tennessee traces the fortunes of a remarkable Black woman and her family through the depression and World War II (1941-45). Finally, Baby Sweet’s takes the story into the 1960s, wrapping up story lines begun in Appalachee Red. The novels particularly describe the world of those whose background includes both white and African American cultures of the period.

After moving to a home near Athens in 1984, Andrews published a memoir, The Last Radio Baby (1990), which described his childhood years when his family lived on the same property with their Black grandmother and white grandfather. Noted newsman and author Charles Kuralt called this book “one of the truest and best pieces of writing I’ve ever come across.”

Andrews’s last book, Jessie and Jesus and Cousin Claire (1991), consists of two novellas. It introduces two powerful African American women who are as unlike as night and day but are similarly determined to have their way. His final manuscript, Once upon a Time in Atlanta, was published in a single issue of the Chattahoochee Review in 1998. All of Andrews’s books were illustrated by his brother, the nationally known artist Benny Andrews.

An expansive, engaging man who made friends effortlessly, Andrews was known for his encyclopedic knowledge of old movies and sports, especially football and baseball, from the 1940s through the 1970s. His modesty and sense of humor, along with a real warmth, made him one of the most widely loved southern writers of his era. He took his art very seriously and laboriously printed his work on yellow legal pads in the mornings, then rewrote and typed the results in the afternoon. He famously enjoyed literary parties and traveled widely to read from his works.

The books of Raymond Andrews have received considerable critical acclaim from numerous critics and other writers. Novelist Richard Bausch aptly described Andrews’s writing as having “a smiling generosity of spirit.” The San Francisco Chronicle called Andrews’s first book “an auspicious beginning for a fine talent,” and the Los Angeles Times said Rosiebelle Lee Wildcat Tennessee had the “infectious exuberance and soul-satisfying warmth of a folk tale.”

In 1989 the Robert W. Woodruff Library of Emory University in Atlanta purchased Andrews’s papers. The Raymond Andrews papers are available for research and include correspondence, photographs, clippings, and drafts and manuscripts of his novels.

Andrews died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in Athens on November 25, 1991.