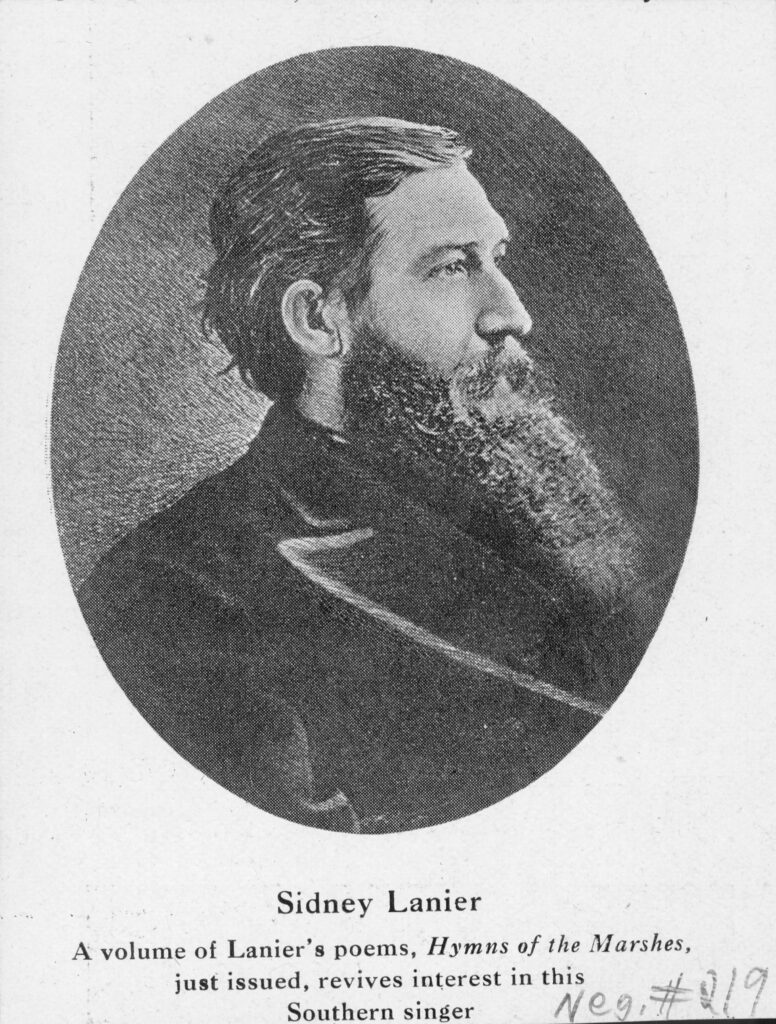

Sidney Lanier contributed significantly to the arts in nineteenth-century America. His accomplishments as a poet, novelist, composer, and critic reflect his eclectic interests, and his melodic celebrations of Georgia’s terrain are among his most widely read poems. His works reflect a love of the land, as well as his concern over declining values and commercial culture in the Reconstruction South. Some of his writings extol the rhythmic natural world and the religious vision it evokes.

Lanier County, formed in southwest Georgia in 1920, is named in the poet’s honor, and Lake Lanier in Hall County was dedicated to him in 1955, in recognition of his life and accomplishments. In 2000 Lanier was inducted as a charter member into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame.

Life

Sidney Lanier was born in Macon on February 3, 1842. He graduated from Oglethorpe University, when it was located near Milledgeville, in 1860 with high honors. When the Civil War (1861-65) began, he volunteered to serve in the Confederate army. In 1864 he was captured and held as a prisoner of war for four months in Maryland, during which time he contracted the debilitating tuberculosis that plagued him for the rest of his life. His marriage to Mary Day in 1867 led to the births of four sons. Rarely fully focused on one occupational pursuit, Lanier had difficulty maintaining steady employment and providing for his family; he worked in Georgia, Alabama, and Texas as a tutor, teacher, and law clerk. He was frequently impoverished and sometimes ill with the ever-present tuberculosis, which was exacerbated by stress and worry. For one school year he was principal of an academy in Prattville, Alabama, but it closed in 1868 in the face of economic depression.

Image from denisbin

From 1868 to 1873, he studied law and worked in his father’s legal office in Macon. Lanier then moved to Baltimore, Maryland, where he accepted a position as first flutist for the Peabody Orchestra. During his years in Baltimore, he studied English literature and eventually became a lecturer at the Peabody Institute and then at Johns Hopkins University. Lanier’s health continued to worsen. He died on September 7, 1881, in Lynn, North Carolina, where he had traveled in the hope that the climate might cure him.

Artistic Works

Lanier’s works reflect his education, his love of literature and music, and his concerns for the Reconstruction South. His first major publication was his only novel, Tiger-Lilies (1867). Depicting the moral and actual tension between devilish Yankee materialist John Cranston and Southern Rebel humanist Philip Sterling before and during the Civil War, the novel balances romantic views of good and evil with realistically portrayed battle scenes. While the novel was unsuccessful, it mirrored some of the painful struggles of the war-torn South. As his focus shifted from poetry to music with his acceptance of the Peabody Orchestra position, he composed his Danse des Moucherons (Midge Dance) (1873) for the flute.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Following this success, Lanier returned to poetry, writing his most memorable poems in a relatively brief period of time. They reflect his accomplished infusion of music into poetic lines. For example, “The Symphony” (1875), thematically an assault upon materialism, is a work of technical virtuosity. Employing remarkable shifts in meter and tone, Lanier structured the poem like the parts of a symphony orchestra. Violins describe the poverty and oppression caused by trade. They are followed by the flute’s description of transcendent nature, the clarinet’s admonition against prostitution, the horn’s celebration of chivalry, and the final plea by “ancient wise bassoons” for a return to innocence. The final lines of the poem reflect Lanier’s desire to spare the postbellum South its suffering, but they also illustrate his artistic vision: “And yet shall Love himself be heard,/ Though long deferred, though long deferred:/ O’er the modern waste a dove hath whirred:/ Music is Love in search of a word.”

Today Sidney Lanier is most noted for his experimental musical renderings of Georgia’s fields, rivers, and shores in such poems as “Corn” (1875), “The Song of the Chattahoochee” (1877), and “The Marshes of Glynn” (1879). In “Corn,” the narrator wanders to the edge of a field of corn stalks that stand in rows like soldiers, born in the field and soon to die there honorably. He recalls how a previous farmer, now fled west, had succumbed to commercialism and “King Cotton” and had suffered great loss. Now the narrator sees the field as returning to its rightful task in producing the older crop. Lanier regarded traditional southern agriculture, rather than commerce from the North, as offering the best hope for the South. In the alliterative and fast-flowing lines of “The Song of the Chattahoochee,” the river speaks of its rush through the northeast Georgia counties of Habersham and Hall. Despite the call to “abide” made by the luxurious native laurels, ferns, grasses, oaks, chestnuts, and pines, as well as the “friendly brawl” of stones and jewels on the river’s bottom, the Chattahoochee insists upon its duty. It must water the fields and turn waterwheels on the plains as it makes its way toward the Gulf of Mexico.

Photograph by Moultrie Creek

Lanier found his purest voice in the religious vision of “The Marshes of Glynn,” which was inspired by the poet’s visit to Brunswick. Set in southeastern Glynn County, the poem begins with a rhythmic description of the thick marsh as the narrator feels himself growing and connecting with the sinews of the marsh itself. Then as his vision expands seaward, he recognizes in an epiphanal moment that the marshes and sea, in their vastness, are the expression of “the greatness of God” and are filled with power and mystery.

Critical Works

Sidney Lanier wrote three texts of literary criticism, two of which were published posthumously. The Science of English Verse (1880), a systematic study of verse forms and methods of versifying, seeks to construct a scientific basis for the writing of verse, and hence, the writing of music. The English Novel and the Principle of Its Development (1883) delineates the development of the Western human personality and its manifestations in music, literature, and science through the course of Western history. Throughout the text Lanier argues that growth in these fields occurs concurrently. Shakspere and His Forerunners: Studies in Elizabethan Poetry and Its Development from Early English (two volumes, 1902) was an outgrowth of his scholarly work as a lecturer at Johns Hopkins University.