Traditionally styled residences, embodying a full range of historical images in what became known as “period” houses, were the hallmark of domestic architecture in Georgia during the 1920s and 1930s.

Responding to a clientele that was well traveled, conservative, and interested in historical styles to dress their home environments, academic architects displayed their knowledge of classicism, turned their more romantic fantasies to medieval revivals or to the Mediterranean style, and found inspiration in America’s colonial building forms. While Georgians were willing to be entertained in an art deco cinema, to visit their doctor or dentist in a modern-styled clinic, or to deal with governmental bureaucracy in a modern classic federal building or county courthouse, most nevertheless preferred traditional designs for their houses.

By the 1920s the twentieth century was progressing toward a modernity that would displace the referential in the art of architecture as readily as canvas painters replaced realism with the nonrepresentational and abstract. Advances in technology and the development of new materials encouraged, by the end of the 1930s and especially after World War II (1941-45), more open plans, expressive structure, and an economy of line and form in residential design. As early as 1925 the French architect Le Corbusier (who changed his name from Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris) equated the house with a machine for living, efficient and productive in providing for the material needs of the dweller. But homeowners in Georgia were slow to embrace the architecture of the new technology, preferring instead the imagery of the past and the traditional features of a conservative home style.

Rising technology, however, did make a significant impact in the lives of Georgians with the emergence of the automobile, which, albeit slowly in the South, eventually brought with it better roads, larger urban developments, and the phenomenon of the suburb. The streetcar was the catalyst for the earliest suburban development in late-nineteenth-century cities, as evidenced by Inman Park (1889), sited at the end of Joel Hurt’s trolley line running east from Atlanta. Nevertheless, it was the automobile and the commuter garden suburb of a rising middle class that characterized the urban development and suburban historicist residential architecture of the late 1910s through much of the 1930s.

Traditionalist Suburbs and Architects

In Atlanta, Druid Hills was designed in 1893 by Frederick Law Olmsted and developed from 1905 to 1936 by his successor firm, the Olmsted Brothers. Ansley Park was developed in 1904 by Edwin Ansley and engineer Solon Ruff. Both neighborhoods targeted the affluent and offered residents a picturesque community that emphasized landscape design and encouraged traditional houses sited in natural settings. Both Druid Hills and Ansley Park attracted the best architects, and today residential work by A. Ten Eyck Brown, W. T. Downing, Hentz and Reid, and others survives in both neighborhoods. Druid Hills’ parkways and bridle paths and Ansley Park’s promotion as the “social and driving center of Atlanta” or “Atlanta’s Social and Driving Center” reflect their position in history at the moment of transition from horse-drawn trolley to the automobile. George Bond’s Briarcliff Plaza (1939), sited at the entry to Druid Hills, and Ivey and Crook’s Rhodes Center (1937), positioned at the edge of Ansley Park, give evidence of an emerging roadside architecture reflecting the dawning age of commuter traffic between work in the city and home in a dormitory suburb.

At the north end of Atlanta, Burge and Stevens and others built homes along a new Peachtree Battle Avenue parkway (Carrere and Hastings, 1911), and country estates spread throughout northwest Atlanta. Soon Peachtree Heights and Haynes Manor began to attract residents to new prestigious suburban streets: Andrews Drive, Habersham Road, Cherokee Road, Tuxedo Road, and the premier street, West Paces Ferry Road, became the most desirable addresses. Philip Trammell Shutze, Pringle and Smith, Ivey and Crook, R. Kennon Perry, and Cooper and Cooper were the principal architects of this district, Atlanta’s ultimate display of suburban historicism. Finally, during the 1930s, Charles Black’s development of Tuxedo Park attracted Frazier and Bodin and others to design large homes with 400-foot front-lot setbacks along Valley Road. Together, these architects and clients created Atlanta’s wealthiest suburban district, which ironically took its inglorious name, “Buckhead,” from the sign of a small tavern sited at the then-rural crossroads.

Picturesque medieval manor houses, such as Cooper and Cooper’s Roper-Riley House (1928-30) or nearby Glenridge Hall (1928-29) were rivaled by a few Tudor or Cotswold-style houses by Pringle and Smith and others. Philip Shutze’s manner was more typically classical, and in its various stylistic permutations, Shutze’s historicism moved in scale and character from the monumental and grand Italianate (Swan House, 1925-28), to the socially proper and elegantly cultivated American Georgian (Knollwood, 1929), to the refined and more restrained Regency or English neoclassical (English-Chambers House, 1929-30). Each presented an image popular at the top of the social register and a “correct” academic architecture that established models for emulation in middle-class suburbs elsewhere in the city and state.

These same architects worked outside Atlanta as well. Neel Reid’s houses in Macon embody comparable historicist values for Macon society. R. Kennon Perry’s Carltonia (1924-25, later Guild Hall) in Newnan, and Hentz and Reid’s Hills and Dales (1914-16), Fuller E. Callaway’s home in LaGrange, are among the fine Tudors and neoclassical great houses respectively in Georgia. Early Robert Pringle houses survive in Rome, and traditional homes continued to be built during the second half of the century by Jimmy Means, Henry Howard Smith, and William Frank McCall, the latter especially in Moultrie.

“Dream” Houses for the Middle Class

Middle-class suburban development at a smaller scale followed and to a degree emulated these prestigious neighborhoods at a more cottage scale. In Atlanta, as suburban development moved northward, on and off Peachtree Road, model houses began to plant images of a simpler English vernacular or of American colonial forms in the minds of would-be homeowners. These suburban homes for the “Everyman” were what historian Gwendolyn Wright has called American “dream” houses.

In 1920s and 1930s middle-class suburbs, European and American traditional styles, marked by picturesque gables, highly textural materials, and a human scale, brought charm (more than high-society elegance) to the architectural palette (and palate). In 1924 a model house appeared on what would become East Morningside Drive, and the development of Morningside’s dream-house suburbia took off. Within a decade a community of meandering streets and small-scale Tudors, colonials, and vernacular Gothic cottages filled the Morningside suburb and, soon, adjacent Lenox Park as well.

During the following three years, a group of Atlanta architects built model homes for Garden Hills: a Dutch colonial by Smith and Downing in 1925; a residence “built along English lines” and another “adaptation of Old English architecture,” both by Burge and Stevens in 1926; and “a graceful triumph of architectural delicacy with an atmosphere of English Tudor,” offered by Cyril B. Smith in 1927. Ivey and Crook’s model of 1925-26 was considered a “Garden Hills 'Home Beautiful,’ a modernized version of the English type of architecture.”

At the end of the decade, Herbert C. Kaiser began to develop Lenox Park (1930-33) and employed Ivey and Crook to design The Barclay (1930-31), The Chateau (1930), and The Sussex (1931-33) as models. The familiar Lenox Park monuments, with an urn atop a brick pier, were designed by Ivey and Crook in the early 1930s, and twelve piers were duplicated in 1989 to define the boundaries and mark the entries into the Morningside/Lenox Park neighborhoods.

The Mediterranean Style—Right for the Region

Amid the northern European–derived cottages of Georgia’s suburban communities were also Mediterranean-style villas, hybrids of Spanish and Italian Riviera forms, thought to be expressions of a southeastern regionalism linked more to Spanish Florida than to the antebellum South. Exemplary on the large scale are Robert Pringle’s Rogers-Haverty House (1921-22) on Cherokee Road in Atlanta, and Pringle and Smith’s nearby Villa Juanita, built as a Spanish villa in 1922-23 and immediately remodeled by the architects to reflect the client’s change of mind in favor of the Italianate. The Mediterranean mode was popularized by G. Lloyd Preacher with Rainbow Terrace (1921-22) in Druid Hills, built for Lucy Candler Heintz, and in his own home (1924) across the street.

Countless anonymous builders also saw the Spanish aesthetic as appropriate to the Southeast region; in Atlanta a section of Sherwood Road has a concentration of houses in the Spanish mode, all dating from 1925 to 1927. Such regionalism was reflected early in George Merrick’s pioneering development of Coral Gables in South Florida, where Merrick sold his first lot in 1921. At least two Atlanta firms participated: Frazier and Bodin list several jobs for Coral Gables houses for Merrick, and Preacher’s office records show jobs calling for 100 homes for the Coral Gables Development Company. Farther up the Florida peninsula, Addison Mizner’s romantic villas in Boca Raton and West Palm Beach combined similar Iberian and Italian elements, which Mizner comparably employed in 1928 for his sole Georgia venture, The Cloister, a resort hotel on Sea Island.

In Atlanta, as early as 1915-16, a more specifically mission revival image had welcomed visitors to the Lakewood Fairgrounds, whose exhibition buildings were designed by Edwards and Sayward. These were perhaps influenced by the more flamboyant 1915 buildings in San Diego, California, built for the Panama-California Exposition by Bertram Goodhue. Mission gables; Spanish wrought-iron ornament; stucco on garden walls, gates, and residences; red pantiled roofing; and a generally exotic flavor were elements of this southwestern and southeastern American regionalism so popular in the 1920s.

Modernism

By the end of the 1920s and turn of the 1930s in Europe, an emerging “white architecture” of German and French modernists was defining a progressive house style that abandoned historic precedent (and rejected any literal adaptation of revivalist styling) in favor of an abstract, volumetric, flat-roofed, ornament-free, and clean-surfaced residential architecture of steel, concrete, and glass. The impact of Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius, who spearheaded the new architecture, would not be felt in Georgia until after World War II.

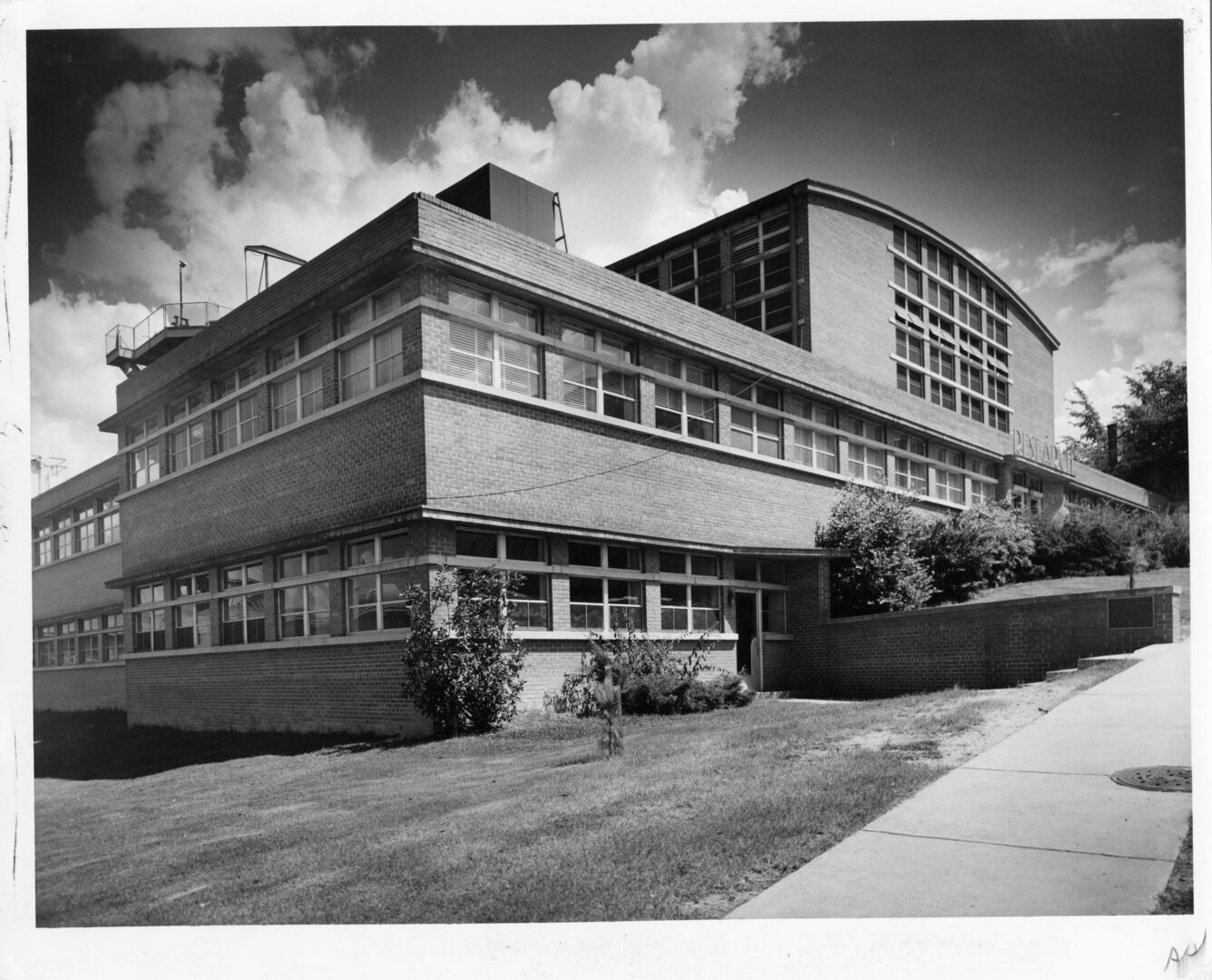

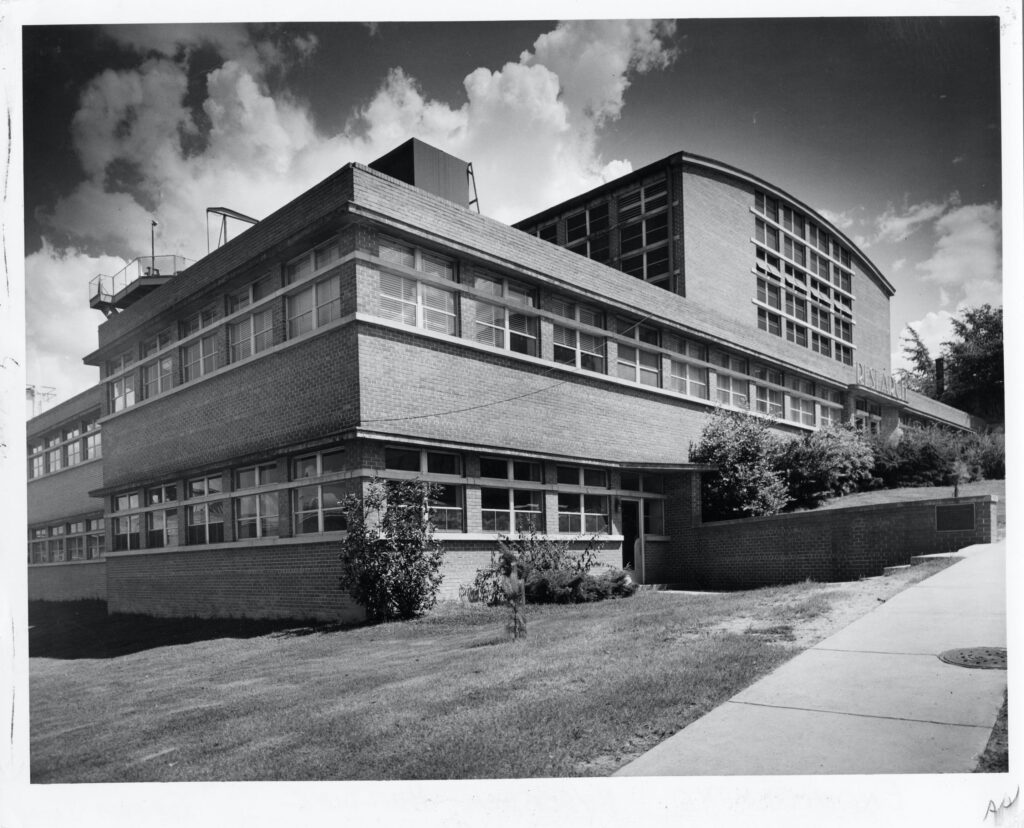

The Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) took the lead in advancing the modern aesthetic. The school’s architecture director, Paul M. Heffernan, built modern buildings on campus, and his functionalist approach to design, along with that of his fellow design faculty (Gropius students, hired from Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts), began after the war to influence a generation of modernists whose houses of the late 1940s and 1950s rejected historicism for modern lines. In Atlanta George Heery (designing a house for himself) and the new firm of Finch and Barnes built houses on Golf View and on the cul-de-sac development of Golfview Road (1951-54), creating a concentration of some of the city’s earliest modern homes.

After his fellowship in 1949-50 with architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who later lectured at Georgia Tech in the spring of 1952, Robert Broward built the Fred Rudder House in Buckhead, later restored by Michael Gamble. A Wrightian aesthetic also appeared in the occasional house designs of Robert Green (who had studied with Wright at his home and architectural school, Taliesin), most notably his Sequoyah for William L. Copeland in Collier Hills (1960-62) and his Arrowhead, a house among other early modern residences in the Amberwood subdivision of the 1960s. A more generic postwar modern house aesthetic, inspired at least in part by Wright’s Usonian houses of the late 1930s to late 1950s, spread single-storied, long and low “ranch” houses of at least partially open plans into suburbs throughout Georgia. Dunwoody and Sandy Springs in the Atlanta area display concentrations of such developments, and there were several early modern architects active in the Valdosta area during the 1950s.

In Savannah a virtual summary of the various stages of house design during the first half of the twentieth century is visible, laid out in sequence as one drives east on Victory Drive, southeast of the city’s historic squares. Various shifts are in evidence, from the high-style historicism of the large Georgian revivals, Tudors, and Mediterranean villas of the Atlantic Avenue area and Daffin Park to the postwar developments on land displacing the old drive-in theater off Victory, as well as north to (and including) the Gordonston district, with its early ranch houses. In such sequences the whole story, from suburban historicism to modern, is evidenced, as it is to varying degrees in many towns across Georgia.