Despite a journalism career with the Macon Telegraph that spanned half a century, Susan Myrick is best known as the technical advisor for the film Gone With the Wind (1939). She also held many other titles in her long and colorful life—educator, soil conservation advocate, civic leader, amateur theater doyenne, and painter.

Susan Dowdell Myrick was born on February 20, 1893. She was the fifth of eight children born to Thulia Whitehurst and James Dowdell Myrick at Dovedale, a family plantation in Baldwin County near Milledgeville.

Myrick taught physical education at her alma mater, Georgia Normal and Industrial College (later Georgia College and State University), from 1911 to 1915. In 1913-14 she pursued advanced studies at the American Medical Missionary College, the premier school associated with the sanitarium run by the Kellogg brothers in Battle Creek, Michigan. Myrick became the public school physical education supervisor in Hastings, Nebraska, in 1916. The following year she attended the Harvard University Summer School of Physical Education in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Myrick then returned to Georgia and worked for the state department of education for the next five years. In 1923 she became director of physical education at the Lanier High School for Girls in Macon.

Myrick began writing short pieces to answer questions that her teenage students were too bashful to ask their mothers. She submitted them to the local newspaper, the Macon Telegraph. These advice columns, titled “Life in a Tangle” and written under the pseudonym “Fannie Squeers,” gained popularity for their mix of humor and common sense. In 1928 Myrick joined the Telegraph full-time, thus beginning a fifty-year association with the paper.

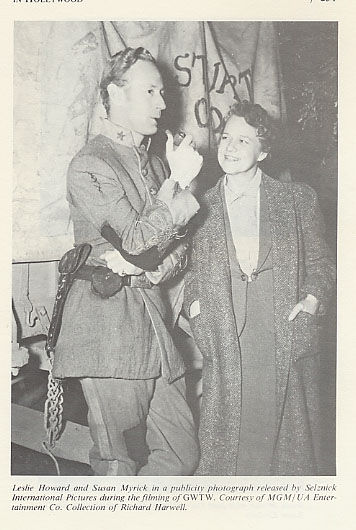

Myrick met Margaret Mitchell at the Georgia Press Institute in Macon in 1928 (the year Emily Woodward founded the annual meeting), and they became close friends. When the filming of Gone With the Wind began, Mitchell wanted no part of the Hollywood scene but worried nevertheless that her book would be given the stereotypical Hollywood treatment of the South. She lobbied for Myrick, her trusted friend and colleague, to oversee details of the film. A Selznick Studios telegram on December 10, 1938, asks Myrick to report to workas the “Arbiter of manners and customs of times as well as [to] tutor members of cast both white and Negro in accent, [according to the] characteristics of each class and time.” Taking a leave of absence from the Telegraph, Myrick arrived in California in January 1939 to begin her $125 a week job.

Despite sixteen-hour days at the studio, Myrick sent columns back to the Telegraph in the form of chatty letters, which describe behind-the-scenes doings on the film set. She was victorious in vetoing such improbable scenes as cotton being chopped in the month of April and Scarlett O’Hara, the main character, carrying a dish of olives (which were not grown on antebellum Georgia plantations). Her major defeat was that Scarlett wears a bonnet during a scene in which she dances with Rhett Butler inside the armory—Myrick’s argument was that no proper southern woman would have worn a hat indoors at an evening party.

After the film’s completion, Myrick addressed audiences nationwide about her advisory role for the production, becoming known as the “Emily Post of the South” for her expertise on southern manners. When the film premiered on television in 1976, she participated in WSB-TV’s preshow production.

During World War II (1941-45), Myrick served as war editor for the Telegraph, handled salvage campaigns and Red Cross drives, and was a member of the Bibb County War Price and Rations Board. She was also a charter member of the Macon Little Theater, serving as its president from 1947 to 1948 and participating in various aspects of amateur theater, including performance, for more than twenty-five productions. In 1950 the Women’s National Press Club in Washington, D.C., honored her for her long years of service and many contributions to journalism.

Myrick wrote Our Daily Bread (1950), a children’s book on soil conservation that was used as an official textbook in Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. As the farm editor of the Telegraph, she was honored statewide and nationally for promoting conservation. She wrote so many stories extolling the virtues of blue lupine as a soil-building, water-holding forage crop that in 1949 the Dooly County conservationists named her their “Bloomin’ Lupine Queen” at a festival held in Vienna. In 1956 she received the Woman of the Year in Agriculture award given by the periodical Progressive Farmer. In 1963 she received a special citation by the National Association of Soil and Water Conservation Districts for her efforts to promote conservation through writing, editing, and speaking.

In later years Myrick continued to serve in several civic organizations, took up painting, and maintained a friendship with John Marsh, Margaret Mitchell’s widower. When the Margaret Mitchell Room was dedicated at the Atlanta Public Library in 1954, Myrick was one of four people asked to contribute an article to the dedicatory brochure. She retired as associate editor of the Telegraph at the end of January 1967, but she continued writing twice-weekly columns. In 1978, despite failing health, Myrick participated in the “Nostalgia Session” of the Georgia Press Institute’s meeting in Athens. Her last column appeared in the Telegraph on August 17, 1978.

Myrick died on September 3, 1978, and was buried in Memory Hill Cemetery in Milledgeville. She never married nor had any children.

In 2008 Myrick was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement.