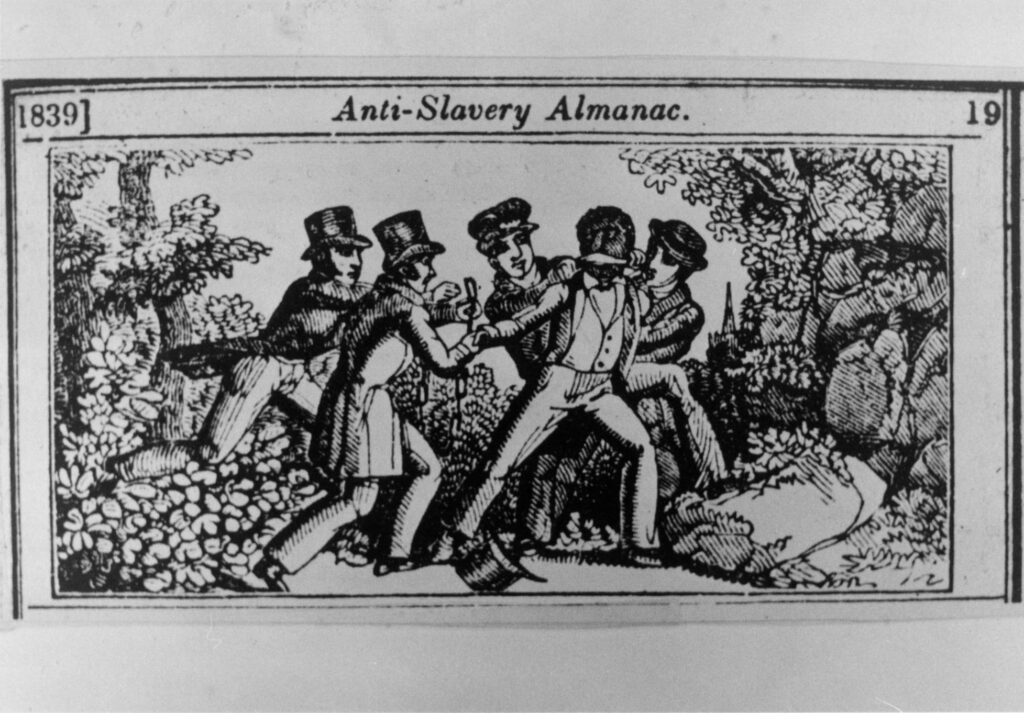

Beginning in 1757 Georgia’s colonial assembly required white landowners and residents to serve as slave patrols.

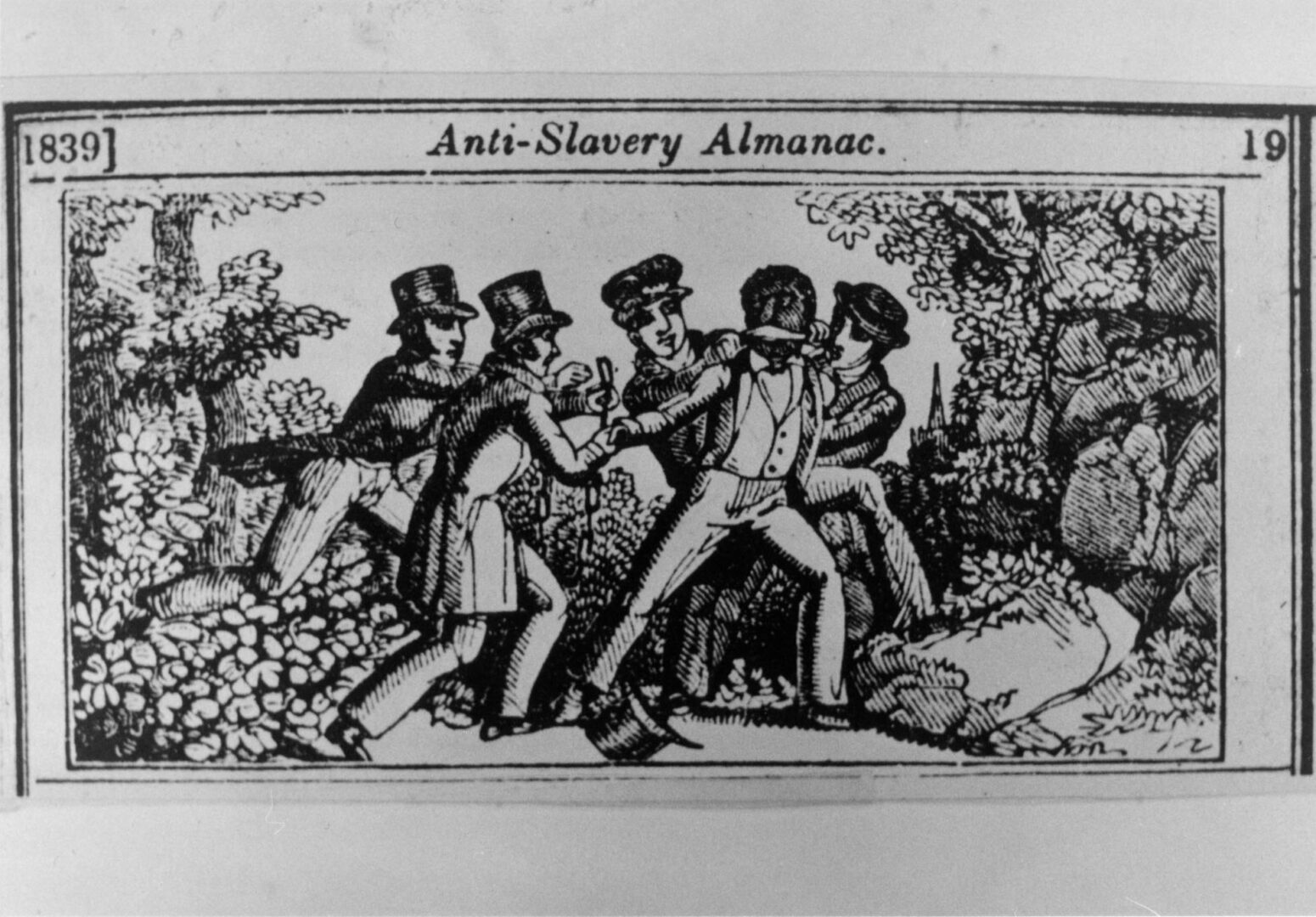

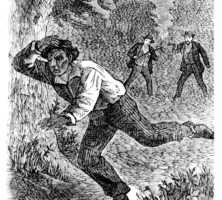

Asserting that slave insurrections must be prevented, the legislature stipulated in “An Act for Establishing and Regulating of Patrols” that groups “not exceeding seven” would work in districts twelve miles square. The statute, modeled on South Carolina’s earlier patrol law, ordered white adults to ride the roads at night, stopping all enslaved laborers they encountered and making them prove that they were engaged in lawful activities. Patrollers required enslaved Blacks to produce a pass, which stated their owner’s name as well as where and when they were allowed to be away from the plantation and for how long. Patrols operated in Georgia until slavery was abolished at the end of the Civil War (1861-65).

Whites could hire substitutes to patrol for them; absentees were fined. Much of the burden of patrol duty fell to nonslaveholders, who often resented what they sometimes saw as service to the planter class. The Chatham County grand jury complained in the mid-1790s about the difficulty it faced in enforcing the patrol requirement. By the early nineteenth century it became necessary to pay people to perform what had been voluntary unpaid service. In 1819 Savannah’s city watch received one dollar for every evening they served and shared in any reward for the forced return of fugitives from slavery.

To disperse any nighttime meetings, patrollers visited places where enslaved workers often gathered. Enslavers feared such gatherings allowed bondsmen to trade stolen goods for liquor and other forbidden items. River patrols were organized in Savannah and Augusta to combat “midnight depredations” and to protect cargo, crops, and other materials piled along waterfront docks from theft. Religious meetings were also a favorite haunt of patrollers because they provided opportunities for socializing that attracted enslaved congregants. After 1792 Georgia law protected religious assemblies from being disturbed, but enslaved and free African Americans could not gather “under pretence of divine worship” contrary to the regulation of patrols. Paranoia over unrest after the Saint Domingue (later, Haiti) slave rebellion of 1791 led to a Savannah ordinance that no enslaved congregants could meet for religious services without a white preacher present.

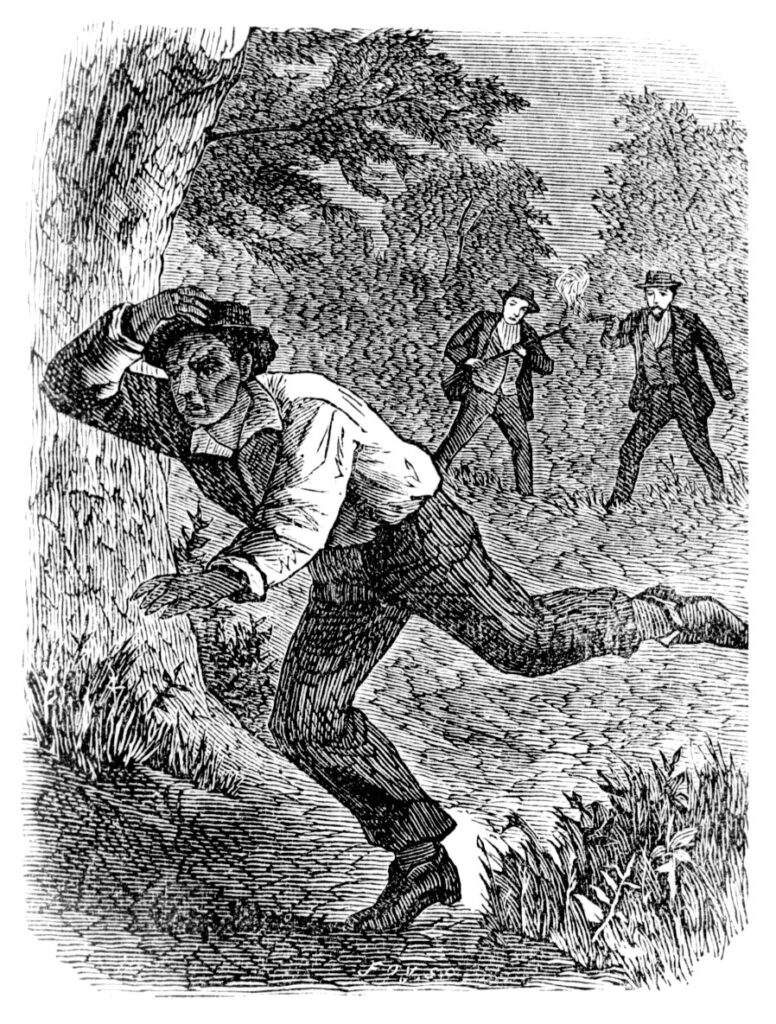

Slave patrols had the legal right to enter, without warrant, the plantation grounds of any Georgian; they often searched quarters and homes of enslaved people, looking for stolen goods, fugitives from slavery, weapons that could be used in an insurrection, or evidence of literacy and education, including books, papers, and pens (teaching enslaved people to read was forbidden by Georgia law in the antebellum period). Enforcement was often more lax than the letter of the law suggested. For instance, in Greene County, in the heart of the plantation Black Belt, the grand jury complained about the laxity of the patrols and their failure to provide effective vigilance over the county’s vast enslaved populace.

In towns and growing cities like Savannah, Macon, and Augusta, slave patrollers usually did their work on foot, and the men chosen as urban patrols were not always well-to-do. The responsibilities of city patrollers occasionally merged with those associated with modern-day policemen and firemen: patrollers investigated strange circumstances (moving lights in a warehouse at night, rowdy gatherings in drinking dens, anyone who acted suspiciously). Indeed, urban patrollers preceded the advent of city policeman and fireman forces in virtually every southern town.

With the Civil War’s outbreak in 1861, white Georgians feared the possibility that enslaved laborers would rebel or that enforcing discipline among enslaved communities would become more difficult. As a result, patrols, often in conjunction with home militia units, intensified their vigilance. Apprehension increased after U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in 1863, and the movement and behavior of enslaved people were more strictly regulated. In Atlanta, for example, patrols began arresting any Blacks found on the streets after nine o’clock at night, whether or not they had passes. City authorities also prevented social gatherings of African Americans unless patrollers or policemen were present.

Although slave patrols ceased to function after the Civil War, they provided the blueprint for later activities of the Ku Klux Klan —a new means by which the white community sought to control the activities of freedmen and freedwomen during Reconstruction.