The history of early Georgia is largely the history of the Creek Indians.

For most of Georgia’s colonial period, Creeks outnumbered both European colonists and enslaved Africans and occupied more land than these newcomers. Not until the 1760s did the Creeks become a minority population in Georgia. They ceded the balance of their lands to the new state in the 1800s.

Early History

The Creek Nation is a relatively young political entity. When Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas, no such nation existed. At that time most Southeastern natives lived in centralized mound-building societies, whose architectural achievements are still visible today in such places as the Etowah Mounds at Cartersville and the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park in Macon.

About A.D. 1400, for reasons still debated, some of these large chiefdoms collapsed and reorganized themselves into smaller chiefdoms spread about in Georgia’s river valleys, including the Ocmulgee and the Chattahoochee. The Spanish incursions into the Southeast in the sixteenth century devastated these peoples. European diseases such as smallpox may have killed 90 percent or more of the native population. But by the end of the 1600s Southeastern Indians began to recover.

They built a complex political alliance, which united native peoples from the Ocmulgee River west to the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers in Alabama. Although they spoke a variety of languages, including Muskogee, Alabama, and Hitchiti, the Indians were united in their wish to remain at peace with one another. By 1715 English newcomers from South Carolina were calling these allied peoples “Creeks.” The term was shorthand for “Indians living on Ochese Creek” near Macon, but traders began applying it to every native resident of the Deep South. They numbered about 10,000 at this time.

Relations with the English

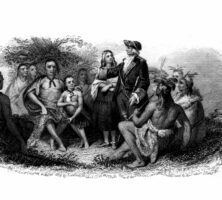

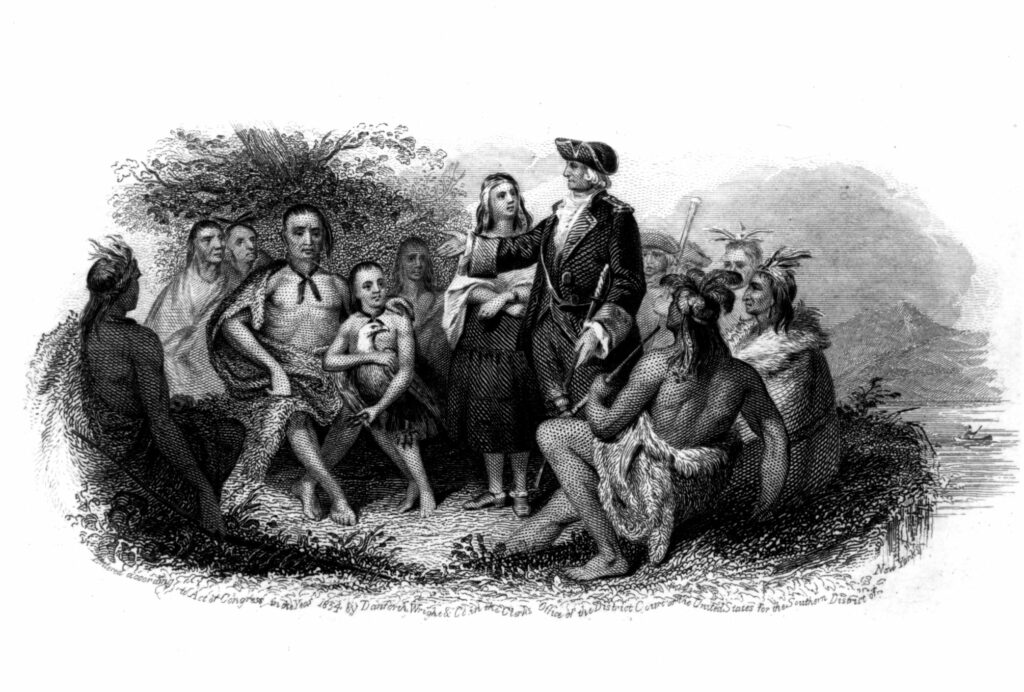

When General James Oglethorpe and his Georgia colonists arrived in 1733, Creek-English relations were already well established. Early interaction between Creeks and colonists centered on the exchange of enslaved people and deerskins for foreign products like textiles and kettles. Soon after the establishment of South Carolina in 1670, the Creeks set up a brisk business capturing and selling Florida Indians to their new neighbors. By 1715 this segment of the trade had nearly disappeared for lack of supply and demand. Deerskins then became the main currency.

By the 1730s tens of thousands of skins were leaving the port of Charleston, South Carolina, each year, bound for English factories, where they were cut into breeches, stretched into book covers, and sewn into gloves. Savannah, Georgia, later joined Charleston as a leading port, and in the 1750s it may have exported more than 60,000 skins each year. In Creek towns the profits from the trade included cloth, kettles, guns, and rum. These items became integral parts of the culture, easing the labor tasks of Creeks. However, they also created conflict by enriching some, but not all, Indians.

The trade also encouraged closer cultural ties between natives and newcomers. Some Georgia traders took up residence among the Creeks, settling in towns on the Chattahoochee, Coosa, and Tallapoosa rivers. They married Creek women and had children, some of whom later became important Creek leaders, such as Alexander McGillivray and William McIntosh. They, along with others, encouraged Georgia’s native peoples to join the plantation economy spreading across the South.

Many Georgia newcomers were enslaved Africans, and they also forged ties with the Creek Indians. Over the course of the eighteenth century, hundreds of fugitives from slavery settled in Creek towns. They, too, shaped the Creek peoples, especially by encouraging them to oppose slavery.

The Road to Removal

Creeks largely avoided the American Revolution (1775-83), but their lives changed dramatically thereafter. The deerskin trade collapsed due to a shrinking white-tailed deer population. The new state of Georgia consequently viewed Creeks as impediments to the expansion of plantation slavery rather than as partners in trade. Under pressure from Georgia, Creeks ceded their lands east of the Ocmulgee River in the Treaties of New York (1790), Fort Wilkinson (1802), and Washington (1805). The first treaty, the Treaty of New York, solidified Alexander McGillivray’s position as a national leader of the Creeks, who were oftentimes hamstrung by a decentralized political system.

At the same time, the United States initiated a program to turn Creeks into ranchers and planters. Although some Creeks willingly embraced the program, many opposed it. Tension between the two factions was so enormous that it erupted in civil war in 1813. U.S. troops and state militias entered the conflict, and in a final, definitive battle in March 1814 at Horseshoe Bend in Alabama, General Andrew Jackson led a force that killed 800 Creeks in battle. The Red Stick War, as it is called, officially ended in August 1814 with the Treaty of Fort Jackson. In this agreement the Creeks were forced to cede 22 million acres, including a huge tract in southern Georgia.

Creeks were soon dispossessed of their remaining land. In the Treaty of Indian Springs (1825), Georgia agents bribed Creek leader William McIntosh to sign away all Creek territory in the state in return for plantation land along the Chattahoochee River. Creeks, who were already outraged by McIntosh’s alliance with General Jackson during the Red Stick War, formally voted to put McIntosh to death for his treachery. Although the United States rejected the fraudulent Treaty of Indian Springs, the Creeks recognized that the Georgia government would not relent. The following year Creek representatives signed the Treaty of Washington, ceding their remaining Georgia land.

Georgia citizens played a central role in removing the 20,000 Creeks still in Alabama. In 1832 the Creeks signed a treaty agreeing to their relocation to Indian Territory (later known as Oklahoma). Land speculators based in Columbus, Georgia, saw opportunity in the Creeks’ misfortune. They illegally purchased Creek lands and then secretly encouraged hostilities between whites and Indians, hoping to spark a war that would clear the Southeast once and for all of its native residents. They found success in a brief conflict between the United States and Creeks in 1836. At its conclusion, U.S. troops, assisted by Georgia and Alabama militia and led by General Winfield Scott, forcibly rounded up Creeks and sent them to Indian Territory. Some went in chains, under the watch of armed soldiers. Creeks had to begin life anew in lands west of the Mississippi.