Located in DeKalb County about ten miles northeast of downtown Atlanta, Stone Mountain is the largest exposed mass of granite in the world. Now a recreational site featuring a carving of Confederate icons, the mountain attracts millions of visitors every year and no small amount of controversy. In 2017 the Southern Poverty Law Center called Stone Mountain “the largest shrine to white supremacy in the history of the world.”

Early History

Archeological evidence indicates that Early Archaic indigenous peoples were the first humans to visit Stone Mountain about 9,000 years ago. In the late seventeenth century Europeans, probably English traders and slave raiders, journeyed to Stone Mountain. Disease followed these Europeans to central Georgia, killing thousands of Native Americans. In response to the threat posed by contact with whites, surviving indigenous tribes made alliances with one another during the late eighteenth century. These alliances became known as the Creek Confederation. Although Stone Mountain lay between the Creek Confederation and the Cherokees, it became an important meeting place, because two major trails connected it to the eastern part of the state. European settlers also increasingly moved into the region during the early nineteenth century.

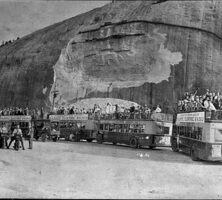

The 1821 Treaty of Indian Springs, which ceded land east of the Flint River, expelled native peoples while opening the land for settlement by European Americans. By the late 1820s, whites had settled the base of the granite mass, and the town was officially named Stone Mountain in 1847. The building of railroads in the 1830s and 1840s allowed local farmers to participate in the larger market economy. Railroads also connected residents from newly settled Atlanta and other cities such as Augusta to Stone Mountain. By 1850 Stone Mountain attracted an increasing number of visitors who admired its natural scenery as well as its fine hotels and man-made attractions.

Quarrying was another business that benefited from railroads in the nineteenth century. Stone Mountain granite was desirable for use as building stone. It was used, for example, on the steps of the U.S. Capitol and in the locks of the Panama Canal. The railroad made it easy for entrepreneurs to transport granite to larger markets. Unfortunately, quarrying also destroyed several spectacular geological features on Stone Mountain, such as the Devil’s Crossroads, which was located on top of the mountain.

Lost Cause Monument

Two events brought Stone Mountain attention during the twentieth century: the founding of the second Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in 1915 and the construction of a large Confederate memorial.

Inspired by D. W. Griffith’s silent film Birth of a Nation (which sanitized the brutality of the Reconstruction-era Klan), William Simmons, a minister and organizer for fraternal associations, planned induction ceremonies to take place a week before the movie’s opening in Atlanta. The ceremonies were intended to arouse the KKK from its forty-year dormancy in Georgia. Simmons secured an official charter from the state, and on Thanksgiving evening of 1915, he and sixteen other members of the new KKK ignited a flaming cross atop Stone Mountain. The second Klan would attract some 5 million supporters by the early 1920s, while promoting violent racism and a nativist agenda.

Even more than the birth of the second KKK, the Confederate memorial gave Stone Mountain notoriety throughout the twentieth century. A product of the Lost Cause era, the memorial was originally conceived as a symbol of the white South in an era of racial segregation. In 1914 the Atlanta chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) advocated for the construction of a memorial on the side of Stone Mountain. Caroline Helen Jemison Plane, the leader of the Atlanta UDC, incorporated the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association(SMCMA) in 1916 and shortly thereafter solicited the support of renowned sculptor Gutzon Borglum, a northerner who had also designed the presidents’ heads featured on Mount Rushmore in South Dakota.

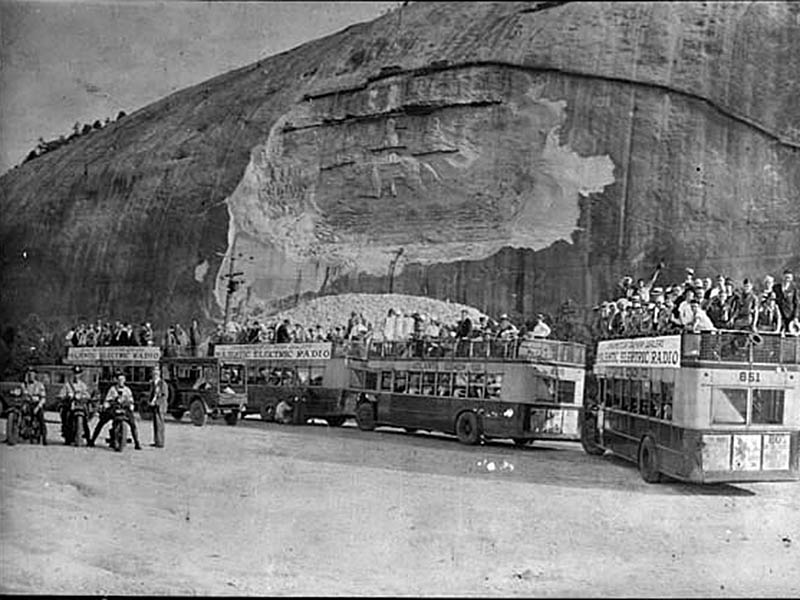

Plane originally wanted Borglum to create a memorial featuring Robert E. Lee leading Confederate troops and KKK members across the mountain’s summit, but the final design omitted the KKK members. World War I (1917-18) delayed the project until 1923. Then, in 1925, with only the head of Lee carved, a growing rift between the sculptor and the SMCMA over artistic control ended with the association firing Borglum, thereby halting construction. With the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Confederate memorial remained unfinished. In 1941 Governor Eugene Talmadge formed the Stone Mountain Memorial Association (SMMA) to continue work on the memorial, but the project was delayed once again by the country’s entry into World War II (1941-45).

It was not until the 1950s, when white southerners were undertaking a campaign of massive resistance to civil rights reform, that interest in (and funding for) the completion of the Confederate memorial was revived. According to historian Grace Elizabeth Hale, “The rising tide of African-American activism in the wake of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision reignited broad interest in Confederate symbols as many white southerners fired up for 'battle’ with the nation again.” In 1958 the state of Georgia purchased Stone Mountain for about $2 million, and Governor Marvin Griffin later signed legislation to establish the SMMA as a state authority. This meant that the SMMA’s nine-member board would be appointed by the governor but that the SMMA would be a self-supporting entity that did not receive tax dollars.

The state and SMMA agreed to carve the images of Confederate icons Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis on the mountain and to construct a plaza at its base. In 1970 planners dedicated the memorial, and an estimated 10,000 visitors came to witness its unveiling. SMMA managed the park until 1998, when the organization entered a public-private partnership with Herschend Family Entertainment Corporation (HFEC). Under the terms of the agreement, HFEC manages all commercial operations in the park, and the SMMA manages HFEC’s lease, maintains public areas, and provides for public safety. The HFEC ended their 30 year lease early in 2018.

Ongoing Controversy

Since the 1980s Stone Mountain has remained a tourist attraction, although many groups denounce the memorial as racist. Tourists from around the world marvel at the natural scenery and enjoy extensive hiking trails, camping venues, and a thirty-six-hole golf course. Other attractions include a reconstructed historic village and plantation, a 1940s train, a skylift, and a waterside complex. Indeed, the site functions as part nature preserve, historic site, and commercialized amusement park. Today, approximately 4 million people visit the park each year.

One of the most popular attractions in the park is the lasershow, which first opened in 1983. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the show “packed such a patriotic punch and conveyed such strong Southern pride that visitors come away from it wanting to kiss their mommas, cheer for the Braves, eat an apple pie, walk on the moon and hunt down bin Laden — all while crooning ‘Georgia on My Mind’ just like Ray Charles.” Changes have been made over the years to reflect technological advances and promote inclusivity. In preparation for the 1996 Olympics, for example, the show symbolized the promise of a New South by illuminating the faces of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks over the Confederate icons. At the time, the show made no mention of the mountain’s connection to the KKK as management sought to “soften the Confederate content.” As a site of heritage tourism, the show’s dominant narrative has faced continued criticism for its portrayal of the Black experience and failure to reckon with the site’s problematic past. Nevertheless, the audience has become increasingly diverse. Local Black residents also regularly visit the park’s outdoor spaces.

In recent years Confederate monuments across the South have come under increasing scrutiny. While the Confederate carving remains in place, plans are underway to add a new exhibit space to better contextualize the controversial site. According to CEO Bill Stephens, this “middle ground” approach will add new structures commemorating other American figures while consolidating (but not removing) the Confederate symbols to one forty-acre section of the park. Some activists, however, do not find these additions adequate, and the site remains a point of controversy.