Eugenic ideology, which aims to increase the occurrence of desired heritable characteristics in human populations through selective breeding, gained traction in the United States during the early twentieth century. In 1937 Georgia became the thirty-second and final state to enact a eugenic sterilization law, with the aim of preventing men and women with “a tendency to serious physical, mental or nervous disease or deficiency” from procreating and passing on their heredity to future generations. Over the next three decades, the state of Georgia oversaw the forced sterilization of more than 3,200 individuals—the fifth-highest number in the United States.

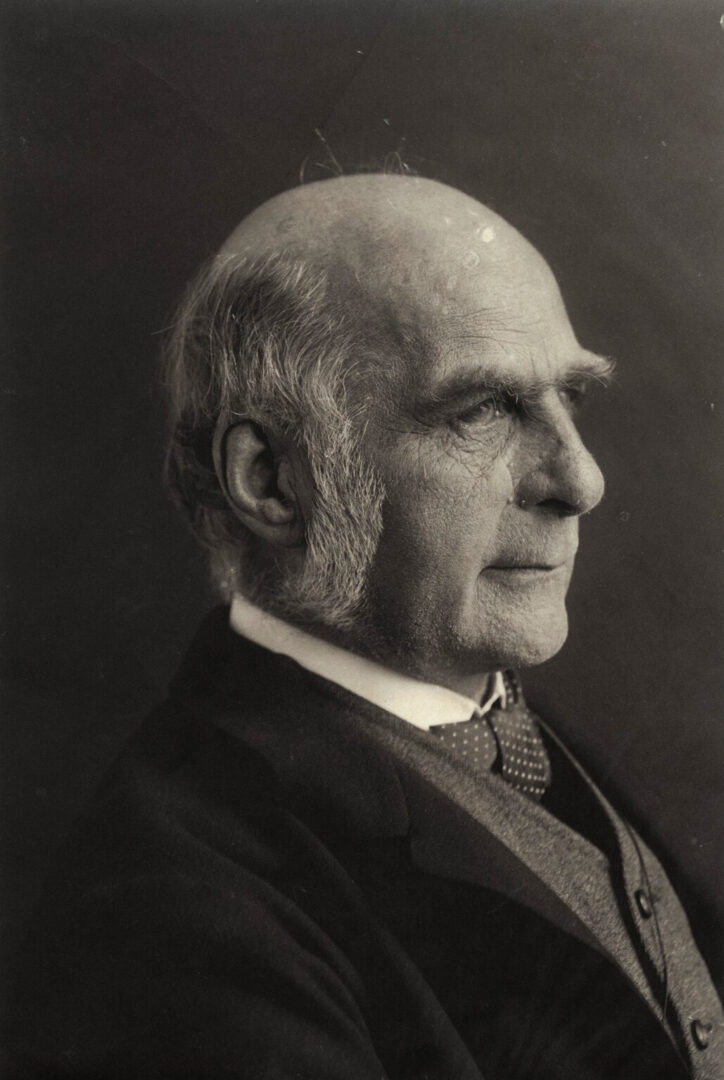

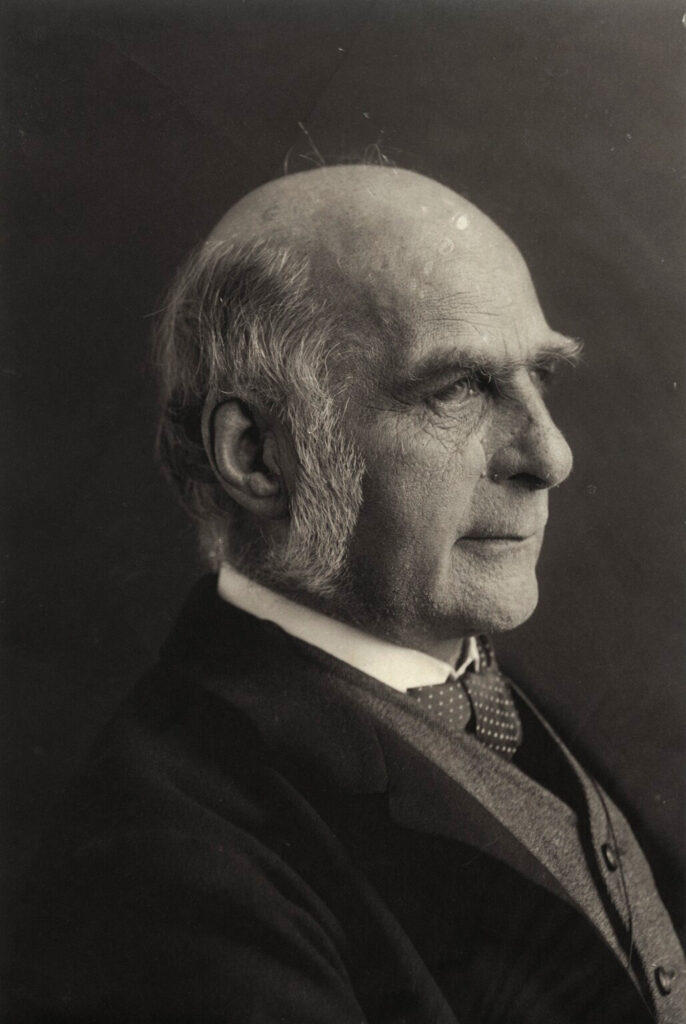

Francis Galton and Early American Eugenics

The field of eugenics was first conceived by English statistician Francis Galton in the mid-1860s, though the term was not coined until 1883. Influenced by the work of his cousin Charles Darwin as well as Herbert Spencer and Gregor Mendel, Galton began to develop his own theories on heredity. He eventually hypothesized that qualities such as intellect and creativity could be actively encouraged (through arranged marriage, pro-natalist policies, and other measures) or suppressed (through segregation or sterilization).

Image from Eveleen Myers

By the turn of the century, Galton’s eugenic ideas had gained the attention and support of many scientific and medical professionals, Progressive-era reform groups, and politicians, among others. The year 1900, in particular, saw a growing interest in the burgeoning “science,” following the rediscovery of Mendel’s laws of heredity by German scientists, the development of surgical sterilization procedures, and August Weismann’s discovery of the “germ plasm.” These scientific advancements occurred at a time when America’s intellectual elite had a growing tendency to associate criminality, disease, poverty, and mental illness with poor heredity, a trend influenced by the dissemination of numerous studies purporting a national rise in mental deficiency and “feeblemindedness.”

Eugenics Legislation in the Early Twentieth Century

By 1907—the year Indiana adopted the nation’s first eugenic sterilization law—eugenics was largely regarded as a legitimate and settled science. Galton’s studies (as well as those of Americans such as Charles Davenport, Henry H. Goddard, and Harry H. Laughlin) influenced both state and federal legislation, especially with regard to foreign immigration. Georgia did not see widespread enthusiasm for the eugenic cause until later, however, and debate on the subject was initially restricted to Georgia’s medical community, mental health officials, and women’s clubs.

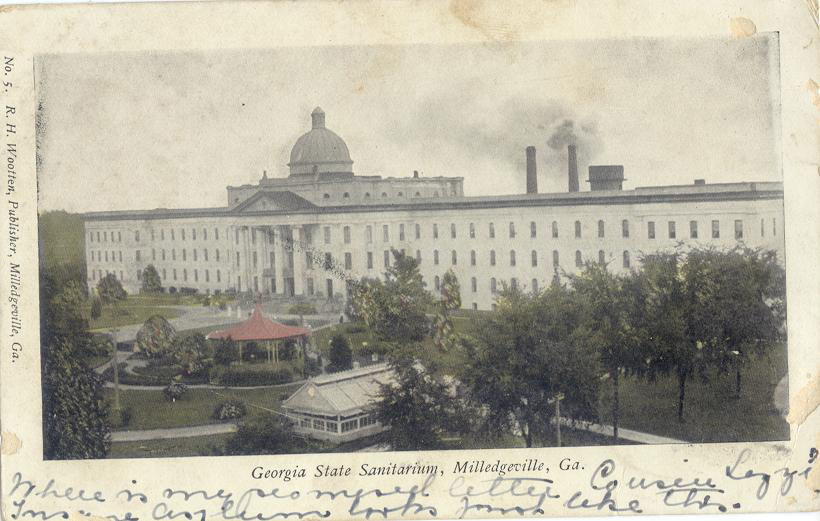

In 1912 Dr. G.I. Garrard gave a presentation to the staff of the Georgia State Sanitarium entitled “Sterilization: The Only Logical Means of Retarding the Progress of Insanity and Degeneracy.” During his presentation, Champion bemoaned the increase in insanity, feeblemindedness, and epilepsy among other afflictions, and became one of the state’s first doctors to publicly espouse the eugenic sterilization of rapists, habitual criminals, and the mentally disabled. The Medical Association of Georgia’s official journal began publishing articles on eugenic segregation and sterilization the following year, and in 1913, trustees of the Georgia State Sanitarium asked Governor Joseph M. Brown for a law that would allow for the sterilization of “certain classes of criminals and defectives.” Brown declined his support, but the request spurred repeated attempts to pass sterilization legislation over the next twenty-five years.

Courtesy of Melinda Smith Mullikin, New Georgia Encyclopedia

By 1918 many of Georgia’s most high-profile physicians and mental health experts were urging legislators to take action against the rising tide of “feeblemindedness.” The following year, the General Assembly passed a bill providing for the segregation and care of feebleminded children, and the Georgia Training School for Mental Defectives in Gracewood opened in July 1921.

The Supreme Court’s 1927 decision in Buck v. Bell, which upheld a law permitting compulsory sterilization of the unfit, reignited the debate over eugenic sterilization. After two proposed bills failed to pass the state legislature, the Medical Association of Georgia announced that it would make a sterilization law one of its top projects for 1934. In a speech given before the Civitan Club of Macon, and later published in (and officially endorsed by) The Atlanta Constitution, Medical Association of Georgia President Dr. Charles H. Richardson outlined the association’s plans, stressing that the state could no longer sustain the ever-increasing numbers of insane and feebleminded within the walls of Georgia’s institutions. Women’s clubs also played an instrumental role in garnering support for a eugenic sterilization bill during the year leading up to the 1935 legislative session. At their annual convention in Macon, the Georgia Business and Professional Women pledged its support to such a law, and both birth control and the compulsory sterilization of the unfit were endorsed in resolutions adopted by the Sixth District Federation of Women’s Clubs meeting in Tennille.

The extensive lobbying proved effective, and in 1935 progressive Democrat Ellis Arnall co-sponsored with Representative Stonewall Dyer a sterilization bill that would allow both superintendents of mental institutions and chain gang wardens to recommend candidates for surgical sterilization. The bill (along with a number of other progressive measures) passed through the Georgia House and Senate without much debate. When it came time to sign the bills into law, however, Governor Eugene Talmadge instead vetoed a record 163 bills and resolutions, including the eugenic sterilization bill.

In January 1937 Lanier County Representative E. D. Rivers was inaugurated governor of Georgia. On the following day, legislators met to begin working on his “Little New Deal,” which eventually expanded Georgia’s state services in health care, education, and housing. The governor’s proposed reforms also included another sterilization bill, this time sponsored by Speaker of the House Roy Harris. The new bill allowed for the sterilization of select “inmates of the State Institutions,” while providing for notice to the guardian or next of kin, as well as the possibility of appeal. The bill passed swiftly through both the House and Senate and was signed by Governor Rivers on February 23, 1937, making Georgia the thirty-second and final state to adopt a compulsory sterilization law.

Eugenic Sterilization in Georgia

Political considerations postponed the Georgia Board of Eugenics’ activation, but within a few years, both the Georgia Training School and the Milledgeville State Hospital had begun to sterilize patients. Still, both institutions proceeded with relative caution prior to the latter half of the 1940s when sterilization rates underwent a dramatic expansion. By the mid-1950s, state authorities were regularly sterilizing upwards of two hundred and fifty patients a year—rates that made Georgia a national leader in compulsory sterilization.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

The number of sterilizations performed at the Milledgeville State Hospital remained high until 1959, when a Pulitzer prize-winning exposé by Atlanta Constitution reporter Jack Nelson shed new light on conditions in the hospital. Though the exposé did not focus on the hospital’s eugenic sterilization practices, the number of operations nevertheless dropped dramatically following its publication, before ending altogether in 1963.

Legislative attempts to encourage sterilization did not cease, however. When the state of Georgia decided to legalize sterilization as a voluntary birth control measure (for married couples) in 1966, legislator John H. Henderson Jr. proposed that the law be expanded so that guardians could seek sterilization for unmarried minors and the mentally disabled. The bill met wide criticism in the legislature and was withdrawn from the floor. Though no eugenic sterilization operations were recorded in Georgia after 1963, it wasn’t until 1970 that the law was finally repealed.