Georgia is one of the birthplaces of the archaeological study of African American sites and artifacts.

Robert Ascher and Charles Fairbanks’s article, “Excavation of a Slave Cabin: Georgia, U.S.A.,” published in Historical Archaeology in 1971, was one of the first national publications on the archaeology of an African American site and signaled historical archaeology’s shift in attention away from plantation houses and their occupants to the people who built and ran the plantations. Over the next two decades Fairbanks, with the University of Florida’s Department of Anthropology, directed graduate theses and dissertations on coastal Georgia plantations that yielded new insights into African American life on the plantations. Subsequent investigations, often completed as part of the cultural resource management studies required under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, have expanded the range of African American site studies to include upland plantations, tenant farms, urban sites, rural communities, and cemeteries. As a result, archaeologists have made contributions to the understanding of African American landscapes, architecture, artifacts, and customs.

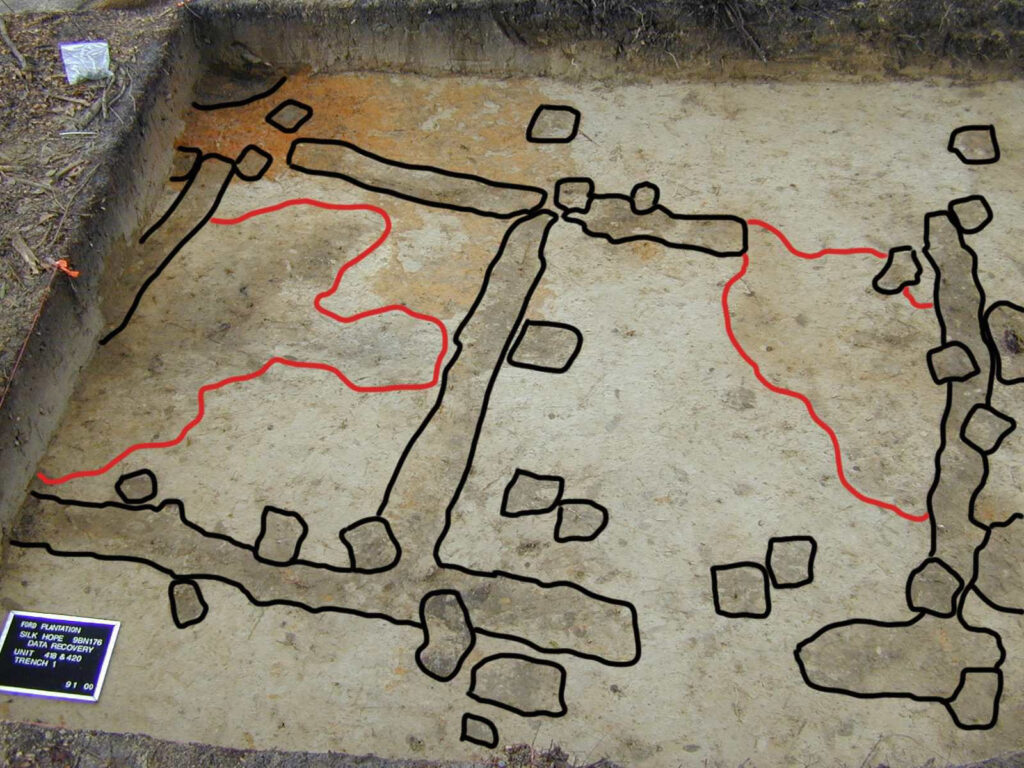

Courtesy of New South Associates

Landscapes

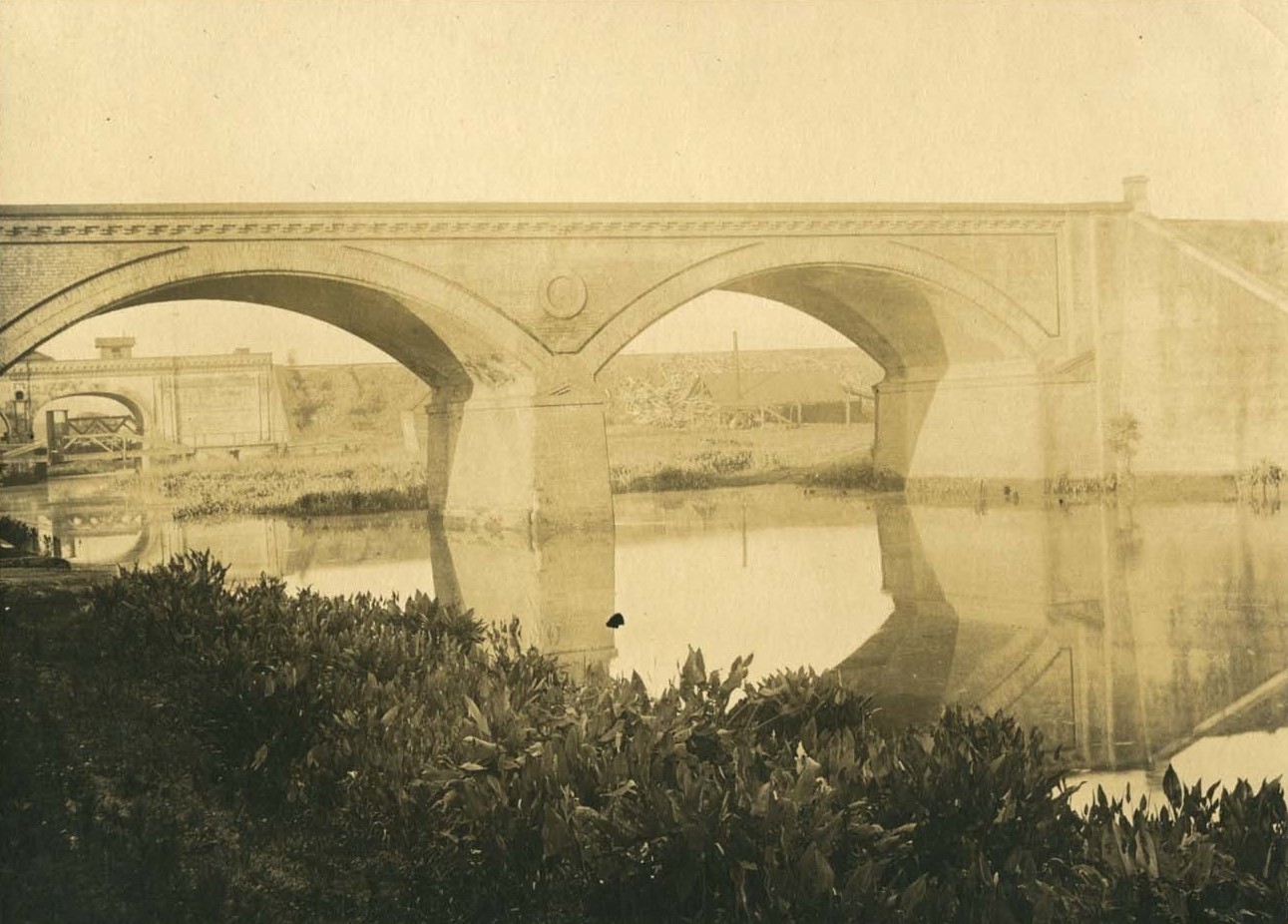

Historians and archaeologists recognize that African Americans transformed the Georgia coast through their efforts in the construction of rice fields and dikes. West Africans were engaged in tidal rice agriculture before their capture and transfer to the New World, and the tidal system of earthen dikes and wooden trunks used to control the flowof water, as employed along the Georgia coast, likely developed in part out of an African tradition. Archaeologists have also examined other earthen constructions completed by enslaved laborors, such as the Savannah-Ogeechee Canal, and in doing so have recognized African Americans’ contributions to the coastal landscape as builders and engineers.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

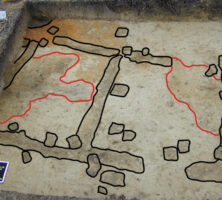

Archaeologists have also learned that early slave villages on the plantations were loosely organized and African in appearance, employing African architectural styles and techniques. As the plantation economy expanded in scale and wealth, planters implemented a more formal landscape plan in which slave villages were organized along streets. While the planned villages were intended to provide better visibility and control to the planters, enslaved people still found ways to avoid observation. Evidence of numerous pit features has been discovered in the yards of slave quarters. Pit features were common to West African village sites, where the pits were used as storage for root crops, soil sources for pottery and building construction, shrines, and trash pits, and their presence in Georgian slave house yards most likely reflects a cultural continuance.

Architecture

Archaeologists have found evidence of African building techniques and styles on Georgia plantations as well as in urban settings. Early African American buildings were constructed using earth-walled and post-in-trench construction techniques, with walls made of rammed earth or wattle and daub (woven sticks covered in clay). These construction techniques were also used in West Africa. Archaeologists and others have considered the possibility that tabby architecture—a building type found along the Georgia coast, where the building material is a concrete formed from lime, sand, and oyster shell—may have developed out of African earthen-walled technology, as it shares the use of wall trenches and forms found on African American earth-walled buildings.

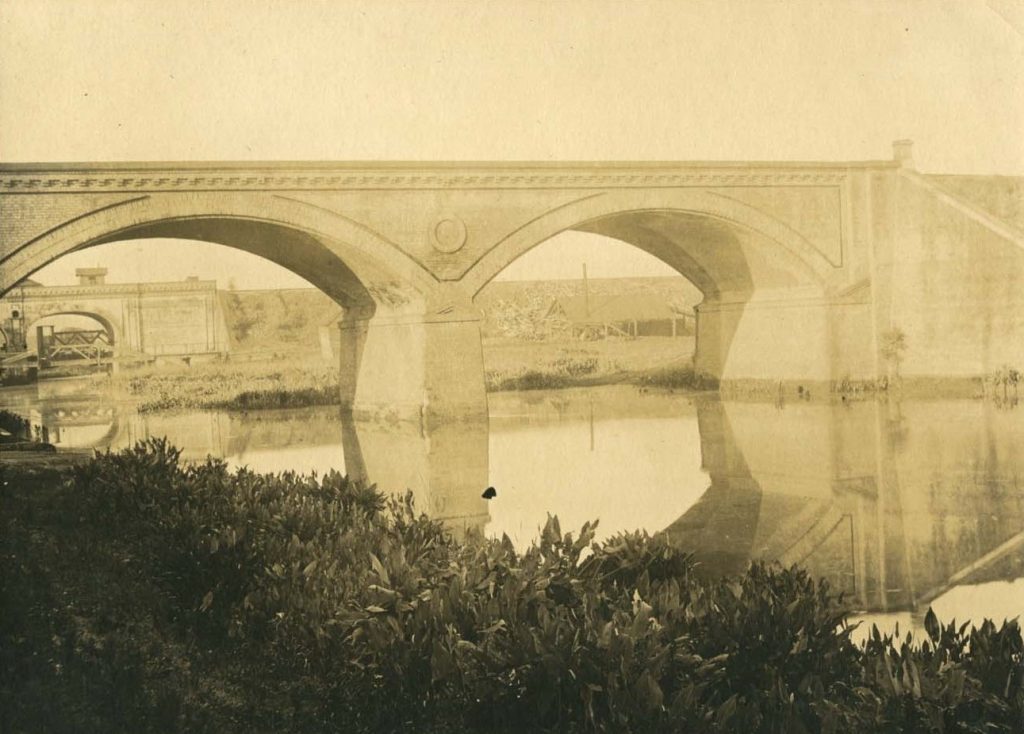

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

African American structures were generally rectangular in shape, as opposed to the square forms preferred by Europeans. A post-in-ground structure dating to about 1850 from the Springfield community in Augusta is similar in form and construction to houses made by the Yoruba in West Africa as well as to Caribbean descendents of this building style. Archaeological studies support research by historian John Michael Vlach suggesting that the southern “shotgun house,” an elongated rectangular house type that is one room wide and two to four rooms deep, developed out of this West African architectural tradition.

Archaeological work suggests that African-styled buildings began disappearing from southern plantations by the 1830s and 1840s, a time in which plantation landscapes were becoming more formal. The loss of this building technology appears to be a product of planters’ desire to shape plantation landscapes, more than African Americans’ abandonment of traditional building forms. Ben Sullivan, formerly enslaved on James Hamilton Couper’s plantation on St. Simons Island, told a Works Progress Administration interviewer in the late 1930s:

Courtesy of Elizabeth Lyon

Ole Man Okra he say we wanted a place like he had in Africa so he built him a hut…. It was about twelve by fourteen feet and it had a dirt floor and he built the side like basket weave with a clay plaster on it. It had a flat roof what he made from brush and palmetto…. But Master made him pull it down. He say he ain’t want no African hut on his place.

Artifacts

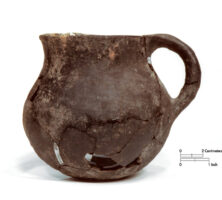

Archaeologists at work on the plantations of coastal Georgia and South Carolina have identified an earthenware pottery that was made, in part, by African Americans. This earthenware pottery was handmade using the coil and pinch techniques, smoothed or burnished, and fired over an open flame. Archaeologists call this pottery colonoware. Appearing medium to dark brown in color, colonoware vessels most typically appear as jars, bowls, and dishes, and archaeological recovery of charred fragments indicates that they were frequently used as cooking wares. Most are undecorated, although some pieces feature piecrustrims similar to British slipwares, and other examples are painted or incised. Archaeologists believe that this pottery developed out of the interactions between African American and Native American enslaved people and was typically made and used by African Americans on the plantation as a household cooking ware. Archaeologists also theorize that as the plantation economy matured, the more accomplished enslaved potters may have made colonoware vessels for sale to southern planters and for sale or trade in the market economy. These better-made wares were thinner and more highly burnished that most of the colonoware found in plantation slave village sites.

Courtesy of New South Associates

Rice and Sea Island cotton agriculture of the Georgia coast was organized using the task labor system, in which enslaved laborers were assigned specific tasks and, once the tasks were completed, allowed to use the remainder of the day for their own purposes. African Americans on task-labor plantations hunted, fished, grew vegetables, and made crafts like colonoware pottery and sweetgrass baskets to generate income, and in certain instances they were able to acquire enough money to purchase their freedom.

Black Georgians continued to develop ceramic folk arts following the end of the plantation era in 1865. Archaeologists have studied terra cotta burial markers found in Milledgeville-area cemeteries that appear to be the work of African Americans at the McMillan brick factory and other local brick factories or of those who worked at some of Georgia’s southern stoneware potteries.

Archaeological studies have also shown how European and American-made artifacts were used in African American households. Excavations of both slave village sites and free Black urban settings show that African Americans preferred hollowares (such as bowls and cups) to flatwares (such as plates and platters). This supports conclusions based on analyses of plant and animal food remains that the African American diet included more liquid-based meals, such as soups and stews, than did European foodways. The preference for liquid-based meals demonstrates a continuation of African cultural traditions.

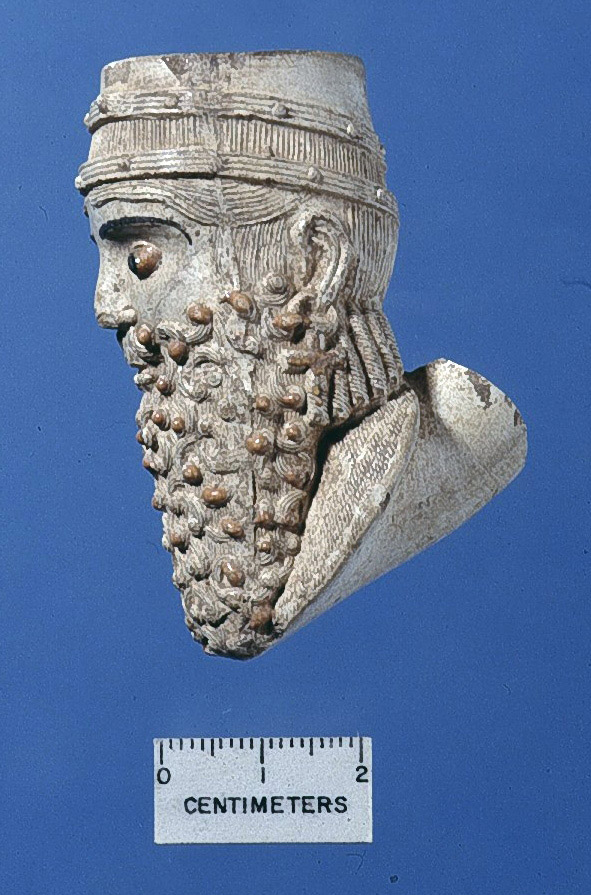

The recovery of a clay tobacco pipe from the free African American Springfield village sites illustrates the ways in which objects contained social and ideological meaning. Augusta laws of that era prohibited Black people from smoking a pipe in public; such “privileges” were reserved for whites. Thus the ownership of an ornate pipe by an African American challenged the laws governing status display. Research identified that the pipe was made by the French pipemaker Gambier, in the figure of a Ninevien. In appearance the pipe resembles a statue excavated by the biblical archaeologist Austen Henry Layard in the 1840s at the ancient town of Nineveh. As the Old Testament tells of God’s freeing the Ninevien slaves, free Black Georgians may have seen hope for the future in this artifact inspired by the archaeology of a biblical town, and may have known of these excavations through the Springfield Baptist Church, one of the nation’s oldest continually practicing African American churches.

Courtesy of New South Associates

Customs and Beliefs

Archaeologists have found evidence of African American customs and beliefs. Xs and other cross marks found on colonoware pottery and other artifacts are believed to represent African symbols, particularly the Bakonogo Cosmogram or dikenga dia Kongo. Archaeologist Leland Ferguson has examined cross marks found on colonoware pottery and believes that cross-marked vessels were used in African rituals and in the preparation of healing medicines.

Elsewhere, archaeologists have found subfloor caches of artifacts in African American plantation dwellings that are believed to represent spiritual caches used to protect healers and shamans. At Cherry Hill Plantation in Bryan County, which dates to the eighteenth century, archaeologists identified a sacrificial lamb burial behind a slave cabin and noted that the archaeological assemblage also included blue beads, mirror glass fragments, a pewter sheep figurine, and colonoware pottery. They suggest that the cabin was the dwelling of a healer or shaman on the plantation. Using GIS, the archaeologists also noted that this cabin was among those least visible to the overseer and planter.

Courtesy of Brockington and Associates

Archaeologists working with African American cemeteries have observed other cultural continuations, including the presence of such grave offerings as broken pottery and glass objects to be used by the deceased; stones, shells, and earth to mark the border of a grave or plot; white or silver objects; and objects associated with water. All these discoveries illustrate the ways that African beliefs and customs shaped Black life in Georgia and elsewhere in the New World.