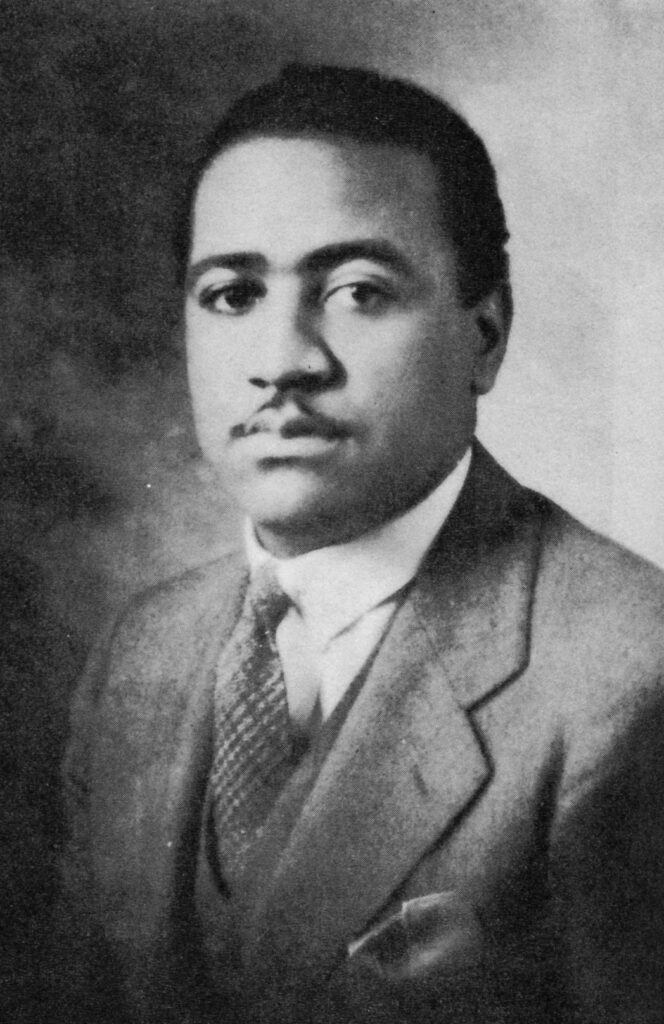

An African American member of the Communist Party, Angelo Herndon won national and international fame as a symbol of political justice after his arrest and subsequent conviction by Fulton County authorities on charges of attempting to incite insurrection in July 1932. Herndon’s case traveled a circular route through Georgia’s judicial system, appearing twice before the U.S. Supreme Court, which ultimately granted Herndon his freedom in April 1937.

Background

After experiencing unprecedented economic growth during the 1920s, the city of Atlanta entered a period of pronounced economic decline during the early 1930s. Depression-era conditions stymied the city’s growth, and Atlanta’s welfare and relief agencies struggled to cope with rising unemployment. Tensions reached a boiling point on June 30, 1932, when more than 1,000 out-of-work laborers marched on the Fulton County Courthouse, demanding the resumption of relief payments that had been suspended only days earlier. Frightened by the prospect of labor unrest, local officials promised immediate relief, and county commissioners approved a $6,000 emergency appropriation at a special session the following afternoon.

Though the measure may have averted the immediate crisis, authorities were nonetheless shaken by the demonstration’s portents of social instability. With the city’s economy struggling to absorb the large number of rural migrants arriving daily to find employment, the suggestion of radicalism amid the ranks of Atlanta’s workers alarmed local leaders. Even more frightening for the city’s officials, however, were the protest’s implications for local race relations. Because the demonstration included Black and white laborers, it represented a startling breach of racial etiquette and threatened Atlanta’s Jim Crow social order.

To forestall future protests, authorities began keeping a close watch on local radicals who were rumored to have organized the protest. After less than two weeks of surveillance, police arrested Angelo Herndon, an African American and avowed Communist, as he collected his mail from a downtown post office.

Only nineteen years old, Herndon had left his home in Ohio five years earlier to find work in the mines of Kentucky. From there, he traveled farther south to Alabama, where he encountered communism in 1930 while working for the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company in Birmingham, Alabama.

Herndon’s brush with Communist politics was not an uncommon experience in the depression-era South; during the 1930s Communist organizers campaigned throughout the region to promote labor reform and interracial cooperation, often arousing the ire of local authorities. Communist teachings on racial equality and class conflict so impressed Herndon that he joined the Communist Party in 1930 and thereafter devoted his energies to the party’s advancement. Alabama officials rewarded his organizational efforts with multiple arrests, prompting a move to Atlanta in the fall of 1931.

Herndon began organizing workers in Atlanta but escaped official notice for several months after his arrival. With his arrest in July 1932 on charges of attempting to incite insurrection, however, the young Communist embarked on a five-year legal odyssey that captured national and international attention and raised prescient questions about the legitimacy of “southern justice.”

Legal Context

However egregious, Herndon’s prosecution was not unique. Following the 1929 stock market crash, politically motivated prosecutions increased in number as state and local governments turned to the courts to maintain social order and suppress radicalism. But if Herndon’s ordeal reflects the political justice that prevailed during the early 1930s, it also belongs to a southern legal tradition that employed state judiciaries as instruments of white supremacy. For this reason the case is often coupled with the notorious Scottsboro trials, in which nine young Black men were wrongfully accused of raping two white women aboard a freight train in northeastern Alabama.

For his Atlanta contemporaries, however, Herndon’s prosecution would have likely brought to mind an incident that occurred closer to home. In the spring of 1930 Atlanta police arrested six radical labor organizers and charged them with attempting to incite insurrection and distributing insurrectionary literature. Like Herndon, the “Atlanta Six” were charged with violating an antiquated insurrection statute dating from the antebellum period.

First passed in 1833, following the slave insurrection in Virginia led by Nat Turner, the law was initially drafted to discourage slave rebellions but was revised soon after the Civil War (1861-65) to combat insurrection. The revised statute largely gathered dust until it was unearthed in 1916 to prosecute the organizer of a streetcar workers’ strike. After another decade of dormancy, the law was revived in 1930 by solicitor general John A. Boykin to pursue labor organizers.

For their defense the Atlanta Six sought counsel from the International Labor Defense (ILD), a New York–based organization that served as the legal arm of the Communist Party. With support from the American Civil Liberties Union, ILD attorneys employed a variety of legal tactics to postpone their clients’ trial until late 1932, when authorities tabled their prosecution in order to focus on the Herndon case. Although none of the accused ever stood trial, formal charges were not dropped for another seven years.

Trials

Like the Atlanta Six and the Scottsboro men before him, Herndon accepted an offer of legal assistance from the ILD, which contracted the case to two young Black Atlanta attorneys, Benjamin J. Davis Jr. and John H. Geer. Their relative inexperience notwithstanding, Davis and Geer prepared a sound defense, questioning the constitutionality of the state’s insurrection law and the legitimacy of Georgia’s all-white juries.

For their part, state prosecutors were content to review the literature seized from Herndon’s apartment; assistant prosecutor L. Walter LeCraw read aloud passages that denounced white supremacy, and lead prosecutor John H. Hudson effectively linked the Communist Party’s advocacy of racial equality to the threat of interracial marriage. If the specter of the South’s greatest social taboo was not sufficient to sway the court’s jurors, then Herndon’s own testimony may have done the job. When he took the stand on the second day of the trial, he courageously defended his party and his politics, and boldly warned that, given present economic conditions, “there will be more Angelo Herndons to come in the future.”

Although it rendered a guilty verdict on January 18, 1933, only three days after the trial opened, the jury recommended mercy, shielding Herndon from a possible death sentence. While Herndon began serving his eighteen-to-twenty-year prison term, attorneys Davis and Geer began preparing an appeal to the Supreme Court of Georgia, which upheld the lower court’s decision in May 1934. A rehearing petition was subsequently rejected as well, thus clearing the way for an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

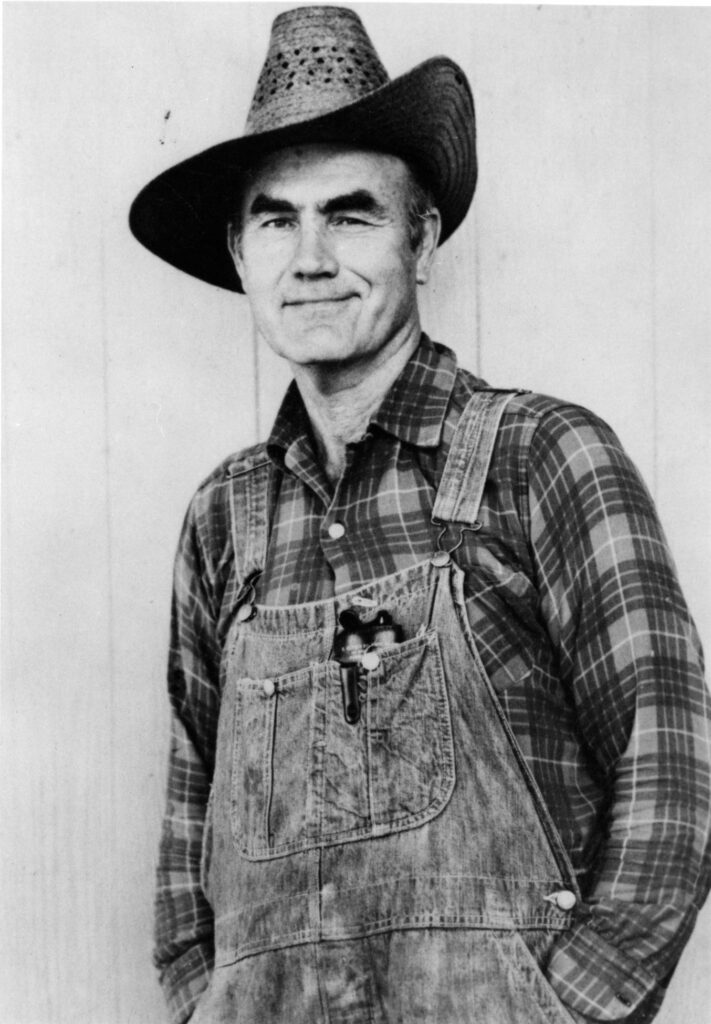

Fulton County authorities vigorously pursued radical organizers after Herndon’s trial, though none of their arrests resulted in convictions. The ILD meanwhile waged a publicity campaign in the national press to win support from northern liberals and create a favorable climate for Herndon’s impending Supreme Court hearing. At the local level, the organization helped establish the Provisional Committee for the Defense of Angelo Herndon, an interracial umbrella group of sympathetic parties briefly headed by the poet and activist Don West.

In May 1935 the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed Herndon’s appeal “for want of jurisdiction,” concluding that the bench could not consider the constitutionality of Georgia’s insurrection statute because the matter had not been properly raised during Herndon’s original trial. In the wake of the court’s decision, the publicity campaign waged in the national press by the ILD during the previous year began paying dividends; columnists in The Nation assailed the court for failing to redress a clear example of “class justice,” and a wide range of interest groups urged the justices to reconsider their decision. However, despite the best efforts of the National Bar Association, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and prominent religious figures, the Supreme Court dismissed the rehearing petition in October 1935.

While the court’s decision may not have secured Herndon’s freedom, neither did it uphold the constitutionality of Georgia’s controversial insurrection statute. Thus no sooner had Herndon returned to prison than Whitney North Seymour, who represented him before the Supreme Court, and Atlanta attorney W. A. Sutherland began preparations for a second round of appeals. Their efforts were rewarded on December 7, 1935, when Judge Hugh M. Dorsey, a former governor serving on the Fulton County Superior Court, ruled the state’s insurrection statute unconstitutional. To no one’s surprise, the Georgia Supreme Court reversed the lower court’s decision, upholding the law’s constitutionality and paving the way for Herndon’s second appearance before the U.S. Supreme Court.

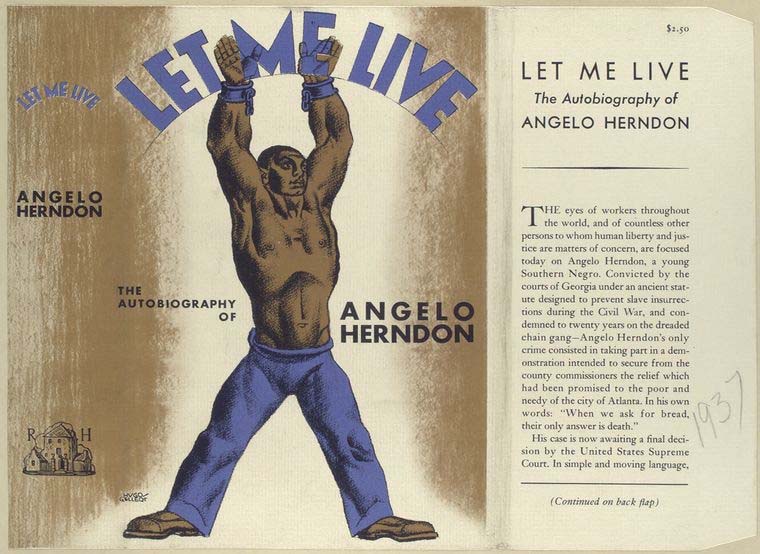

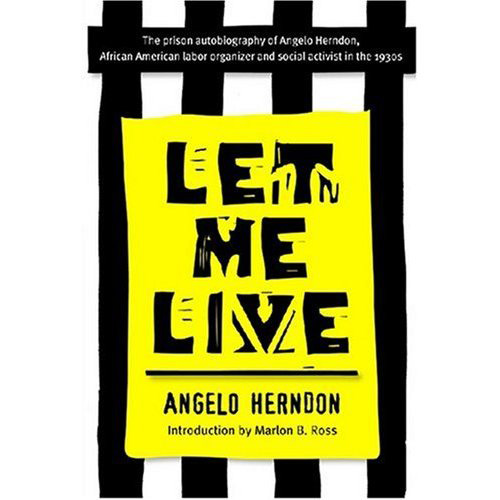

The case of Herndon v. Lowry appeared before the court amid great fanfare in February 1937. Herndon’s story, by now familiar to civil libertarians and a broad cross section of national liberals, received even greater attention with the appearance of his autobiography, Let Me Live, which was written while he was in prison and published in March while the Supreme Court debated his future. On April 26, 1937, a narrow five-to-four majority ruled in Herndon’s favor, striking down Georgia’s insurrection statute. The emerging liberal bloc that exonerated Herndon subsequently provided a majority in a series of rulings that significantly expanded First Amendment rights.

For Herndon the court’s ruling represented the culmination of a five-year struggle that restored his freedom and elevated him to celebrity status as a symbol of political justice and judicial excess. He remained active in the Communist Party for the next decade or more, serving in a variety of administrative capacities and contributing occasional articles to party publications. In the early 1940s he coedited a radical journal of letters, Negro Quarterly: A Review of Negro Life and Culture, with author Ralph Ellison. By the end of the 1940s, however, Herndon had parted ways with the party and moved to the Midwest, where he lived quietly and worked as a salesman.

A stage adaptation of Let Me Live, written by playwright OyamO, was produced in 1991 at the Working Theater in New York City. Herndon died in December 1997.