In March 1960 students representing Atlanta’s historically Black colleges formed the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights (COAHR) to lobby for the desegregation of the city’s lunch counters. After a year of demonstrations and failed negotiations, downtown retailers submitted to the organization’s demands. Thereafter, COAHR worked in concert with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to compel the desegregation of local restaurants and hotels. The two groups achieved limited success, however, and citywide desegregation did not occur until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Background

In February 1960 four African American college freshmen capturednational attention when they refused to leave their seats at a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. In the months that followed, students throughout the region staged similar protests, and student activism emerged as an important component of the civil rights movement.

With six historically Black colleges inside its city limits, Atlanta was no exception. Since Atlanta enjoyed unrivaled prominence as the region’s capital of commerce and industry, student protest in the city assumed wider significance. National observers followed events in Atlanta with interest, and many public opinion makers speculated that the city would become a bellwether of regional change. As one national publication, Look magazine, predicted, as goes Atlanta, so goes the South.

In the wake of the Greensboro sit-ins, students began meeting informally to discuss the prospects for protest in Atlanta. Dissatisfied with the city’s slow pace of change, student leaders Lonnie King and Julian Bond proposed waging a sit-in cam paign to compel the integration of area lunch counters, and they began recruiting like-minded classmates to support the cause. Planning for the demonstrations was under way when the students were summoned to appear before a special meeting of Atlanta University Center’s Council of Presidents. Although some council members indicated a preference for pursuing a legal strategy, the council endorsed the campaign but urged the students to announce their position in writing before undertaking organized protest.

At the council’s behest, members of the All-University Student Leadership Group published “An Appeal for Human Rights” in local newspapers, including the Atlanta Constitution, Atlanta Journal, and Atlanta Daily World, on March 9, 1960. In unambiguous terms the appeal denounced segregation as both a moral failure and an offense to the country’s democratic traditions. Citing numerous “inequalities and injustices” in education, housing, voting, health, employment, and law enforcement, the document challenged city officials and “people of good will” to live up to Atlanta’s progressive reputation, while warning that failure to do so could result in sustained protest. “We must say in all candor,” the document concluded, “that we plan to use every legal and non-violent means at our disposal to secure full citizenship rights as members of this great Democracy of ours.”

The appeal’s publication quickly became a subject of interest in the local press, where most columnists applauded the students’ commitment to nonviolence. Other observers, however, were less impressed. Governor Ernest Vandiver Jr. dismissed the appeal as a “left wing statement… calculated to breed dissatisfaction, discontent, discord, and evil,” and speculated that foreign radicals may have been the manifesto’s actual authors. Atlanta’s pragmatic mayor, William B. Hartsfield, meanwhile thanked the students for “letting the white community know what others are thinking” but took no immediate steps to address their grievances. The appeal received some national attention, as well, after it was excerpted in the New York Times the following week.

Sit-ins Begin

On March 15, six days after the appeal’s publication, the All-University Student Leadership Group initiated a series of carefully orchestrated sit-ins at ten lunch counters and cafeterias throughout the city. Although police arrested 77 of the nearly 200 students who participated, no violence occurred, and the organizers declared the protests a success. The following day student leaders announced that the sit-ins would be suspended, pending negotiations with representatives of the business community. Representing the students at the negotiating table would be the newly formed COAHR, which was chaired by Morehouse College student Lonnie King and Spelman College student Herschelle Sullivan.

At the first meeting business representatives demonstrated little interest in compromise, and the students went away disappointed. COAHR thus resolved to resume protests, this time targeting specific businesses. The new strategy produced uneven results, however, and little progress had been made by May 1960, when protest was for the most part suspended until classes resumed the following fall.

The Fall Campaign

Protest planning resumed with renewed vigor when students returned to campus in September 1960. COAHR members delayed the fall campaign to coincide with the presidential election, because they hoped to gain national attention and help make civil rights reform a subject of national debate. On Wednesday, October 19, after more than a month of planning, students launched a new round of sit-ins focusing on a handful of businesses, including the Magnolia Room restaurant at Rich’s Department Store, Atlanta’s largest retailer. (Many lunch counters were located within department stores, such as Rich’s and Woolworth’s.) More than fifty demonstrators were arrested on the first day of the campaign, including A. D. King and his brother, Martin Luther King Jr., whom the students had persuaded to participate in a bid for greater publicity. Perhaps as a result of King’s arrest, protests increased in size and number the following afternoon, when more than 2,000 students closed 16 more lunch counters.

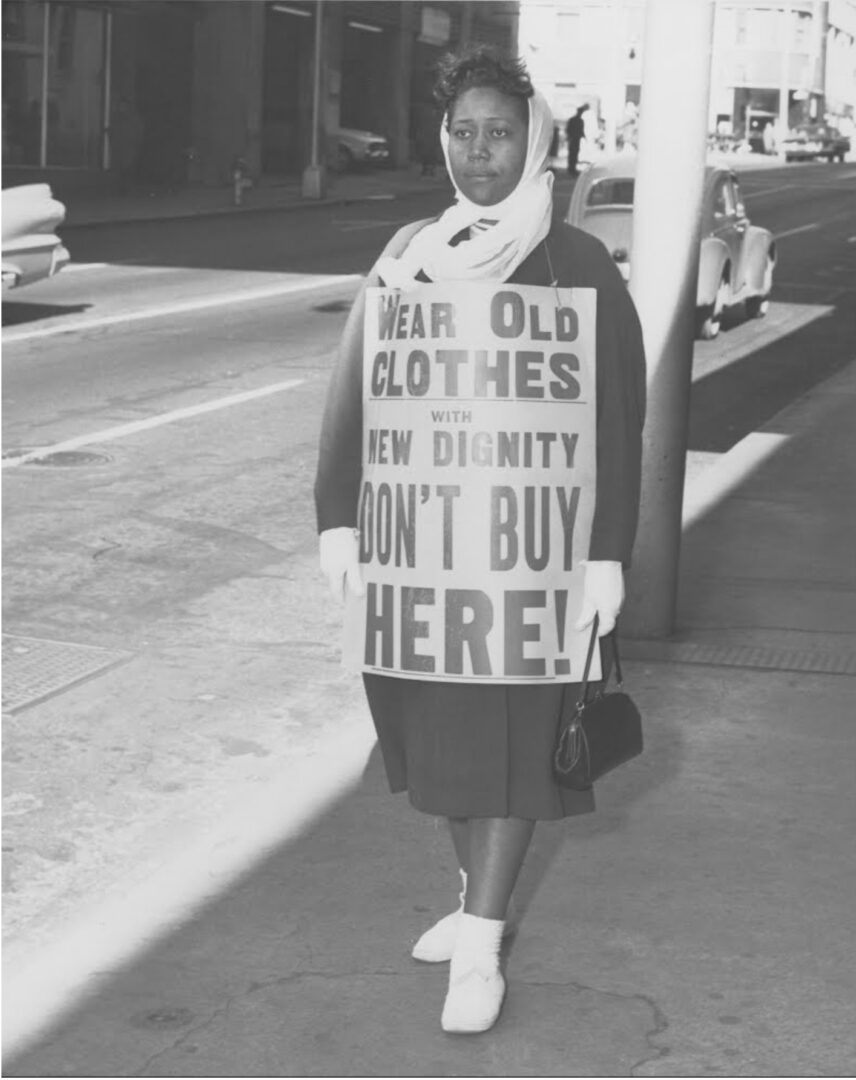

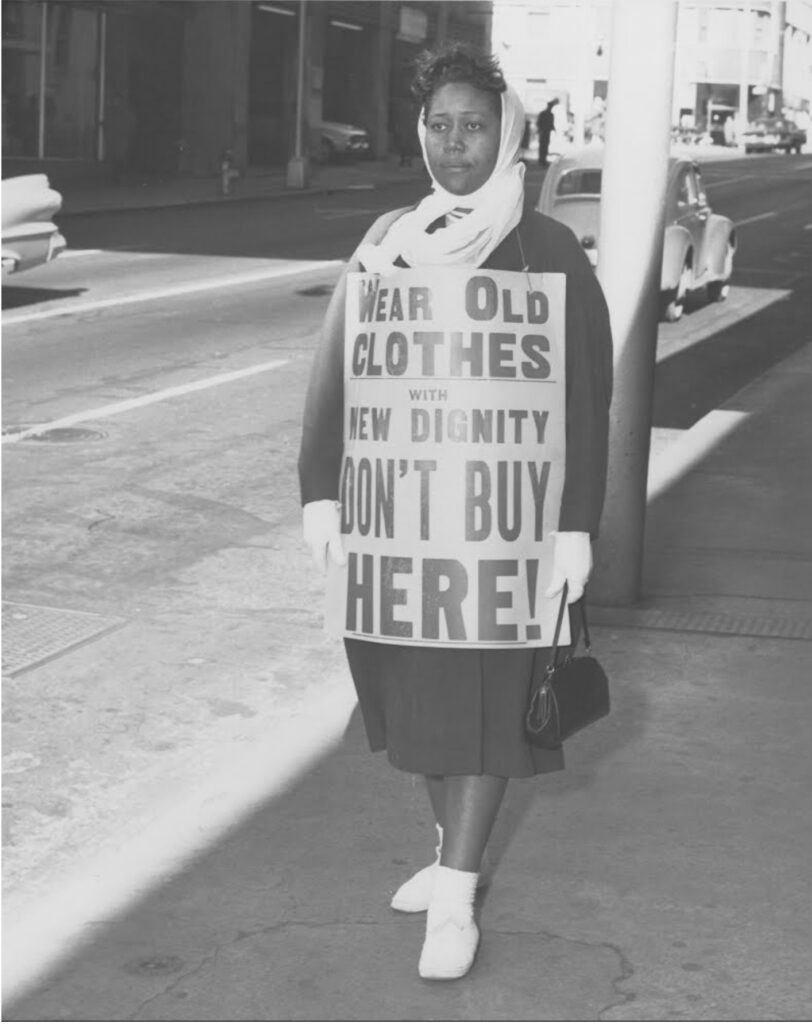

By Saturday, tensions had reached unprecedented levels; counterdemonstrations by Ku Klux Klan members threatened civil unrest, and COAHR called for a wider boycott of downtown businesses to “bankrupt the economy of segregation.” To preserve the city’s vaunted racial climate, Mayor Hartsfield secured the release of twenty-two jailed demonstrators and arranged a thirty-day truce wherein negotiations between student and business leaders could transpire. For this second round of negotiations, student leaders were joined by elder members of the city’s Black establishment under the auspices of the Student-Adult Liaison Committee, which was formed the previous summer to assist and influence the student movement. The city’s business community remained opposed to desegregation, however, and some key business leaders refused to negotiate altogether. As a result, protests resumed when the thirty-day truce expired, forcing the closure of all downtown lunch counters by the end of November.

Over the course of the next three months, protests continued unabated, and COAHR implemented a new strategy: demonstrators who were arrested would refuse bail, in order to crowd the jails. Sales figures released at the end of 1960 indicated a 13 percent decline compared with the previous year, confirming that the student-led boycott had significantly affected the downtown businesses. Whether because they could not withstand the financial pressure, or perhaps because desegregation elsewhere in the state suggested the inevitability of change in Atlanta, area business leaders indicated a new willingness to compromise during the early months of 1961. While students tarried in local jails, white business leaders met privately with their counterparts in the city’s Black establishment to negotiate a settlement to the desegregation stalemate.

On March 7, 1961, student leaders King and Sullivan were summoned to a downtown meeting, where they learned that the city’s white and Black leaders had brokered a deal to desegregate the city’s lunch counters. Under the arrangement, desegregation would occur the following fall, following the court-ordered integration of local schools. Although they objected to the delay and felt betrayed by their elders in the Black community, King and Sullivan ultimately consented to the settlement.

Aftermath

In the wake of the agreement, students and residents alike expressed dissatisfaction with elder members of the city’s Black leadership and openly questioned the decision to postpone desegregation. Tensions reached a boiling point at an emergency public meeting held by the Student-Adult Liaison Committee on March 10 before an audience of approximately 1,500 people at Warren Memorial Methodist Church. Although they listened politely during opening remarks, audience members became restive during the question-and-answer session, and rumblings of disapproval soon gave way to outright hostility. Hecklers dismissed speaker A. T. Walden as an “Uncle Tom” and brazenly questioned the integrity and usefulness of such seasoned community leaders as Martin Luther King Sr. and William Holmes Borders. Only an impromptu call for unity by King Jr. quelled the growing dissent. In what some observers later called his most compelling address ever, the civil rights leader implored audience members to resist the “cancerous disease of disunity.” “If anyone breaks this contract,” King Jr. concluded, “let it be the white man.”

King’s oratory would not paper over future generational conflicts so easily, however, and over the next few years older members of the Auburn Avenue elite slowly ceded authority to a younger, more assertive group of community leaders. The students of COAHR meanwhile continued to press for an open city, working in concert with SNCC to secure the desegregation of area hotels and restaurants. Although a limited number of Atlanta’s restaurant owners and hoteliers agreed to admit Black customers in 1963 after sustained protest by the two student groups, more than half later reneged on their agreement.

Despite its carefully cultivated reputation for harmonious race relations, Atlanta actually lagged behind many of its neighbors in desegregating local institutions. When a small group of students launched sit-ins in Savannah only a few days after their peers in Atlanta, for example, they enjoyed the full support of the city’s Black leadership. After continuous protest, all of the city’s lunch counters desegregated within eighteen months, and Savannah was an open city by October 1, 1963. Although students in Rome waited until the summer of 1963 to initiate sit-ins, they secured the desegregation of area lunch counters by the end of the year. Regionwide, no less than 103 cities across the south had already desegregated lunch counters by October 1961, when Atlanta retailers desegregated after the successful integration of the city’s public schools. Future desegregation was “piecemeal and sporadic,” according to historian Stephen Tuck, and the city remained largely segregated until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.