Women were important in the settlement of colonial Georgia from its very beginning in 1733. The founding Trustees of the Georgia colony understood “how necessary a Part Women are in a family” and wanted them to fulfill their traditional roles. The tasks of men and women in a frontier society were complementary; the agricultural and charitable goals of the Georgia colony required both for labor and stability. Throughout the colonial period women migrated and settled with families and religious groups, or sometimes as individuals seeking a new start. They came as wives, mothers, daughters, or sometimes alone as indentured servants or enslaved workers. They were English, Salzburger, German, Scots, Irish, Sephardic Jews, and after 1750, African. Native American women also became part of the colonial fabric, although they did not come under the governance of the colonial government.

White women had a clear place in the Trustees’ vision of the colonial Georgia society as a land of hardworking, yeoman farmers providing needed products to England. But in a colony that was also intended to protect the exposed southern edges of the British North American frontier from Spanish and French designs, the presence of women was problematic. Men could both farm and fight, but women could prove a liability in the military operations of the colony. Early Trustee policy sought to solve this difficulty with the establishment of policies and regulations that assured defensive preparedness.

In the early years land was granted to males and could be inherited only by males. Land belonging to male colonists who died without male heirs reverted to the Trust for regranting to male citizens. Male colonists who settled in Georgia at the expense of the Trust were limited to fifty-acre grants, and even those paying their own way, who could receive up to 500 acres in granted land, had to have a male servant or family member for each fifty acres of their grant. This assured men for the defense of the colony. Otherwise, said Trust secretary Benjamin Martyn, “The Strength of each Township would soon be diminished…. Every Female Heir in Tail, who was unmarried, would have been intitled to one Lot, and consequently have taken from the Garison the Portion of one Soldier.”

Reaction to this policy was swift; the earliest colonists protested it. Men wanted their wives and daughters to inherit land, because a man “could never enjoy any peace of mind, for the apprehension of dying there, and leaving his child, destitute and unprovided for, not having the right to inherit or possess any part of his real estate.” Salzburgers pointed out that “the female as well as the Male Sex have left their country for the Sake of the Gospel.”

From the beginning the Trustees made exceptions and gradually began to change the policy to allow widows and daughters to stay on land. Early misgivings about female colonists began to fade. Founding Trustee James Oglethorpe increasingly came to appreciate the value of women, even in the southern garrison towns closest to the Spanish border. Oglethorpe encouraged the Trust to send “industrious” wives with recruits because “single men are very great inconveniences.” Efforts increased to give passage to wives, sisters, and daughters.

Family formed the basic structural unit of society, and so marriage was encouraged. The imbalance of males and females made women valuable and marriageable. The male was the head of the family who exercised the legal rights of the household. A married woman was a “feme covert” whose legal existence, according to British law, “was suspended during the marriage, or at least incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband.” A feme covert did have dower rights, which gave her claim to property in case of a husband’s death; she had to renounce this claim of dower to any land of the husband before he could sell it.

Another protection that some women used in Georgia’s royal period was the premarriage agreement, which set a woman’s property aside in a trust to which her husband had no access. The woman kept the right to the property she brought into a marriage, including the sole right to sell it and to choose her heirs. Most women who exercised this right were upper class and were widows about to marry again.

A woman was to be “a loving Wife, an affectionate Mother, and a true Housekeeper.” Divorce was not allowed, but some women escaped from marriage by running away, although there were few ways for them to support themselves. Most marriages, however, ended because of the death of one of the partners, and in early Georgia that could mean short marriages and equally brief widowhoods. Most men and women remarried quickly, because marriage was an economic and practical necessity.

Children also contributed to growth and stability in the colony, and having “fine” children was one of the important functions of wives. Aware of the perils of childbirth, the Trustees provided for a public midwife at Trust expense, first in Savannah and later in both the northern and southern divisions of the colony; it was the only government position funded for a female. The midwives received a salary of five pounds per year, plus five shillings per “laying.” They were required to attend to the poor and to indentured servants. The Trustees also sought to ease the pain of women “brought to bed” by providing an allowance of wine for women in labor. In addition to their reproductive labor, women were also producers, running households, preparing food and clothing, and helping with planting and harvesting when necessary.

Besides being wives of farmers and planters, women sometimes owned land outright. Few women owned land in the Trustee period. In the royal period, however, the number of women owning land and the amount of land they owned both rose. Women received headright grants of land from the government and also purchased land for themselves. Anybody applying for a headright grant could receive a grant of 100 acres, plus an additional 50 acres for each member of the household, including enslaved people and indentured servants. (In 1777 the initial allotment per settler changed to 200 acres.)

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

By the end of the royal period, women had received more than 70,000 acres under the headright system. While some of these grants were for town lots, many were for farm acreage. Most farms were of modest size, less than 500 acres, but a few women acquired larger tracts, some more than 1,000 acres. Those with larger estates were, like their male counterparts, enslavers.

The typical female landowner was a widow; most other women with their own land were spinsters, or women who had never married. If a woman received a headright grant and later married, then ownership of the property would revert to her husband. Property was important to the self-sufficiency of women who outlived husbands or never married. Most female-owned farms were in the more settled areas of the colony.

Although most women contributed to colonial Georgia through their work in households and on farms, some ventured into other areas. In the Trustee period women were also to be the backbone of the industry that the Trust and crown both hoped would become a major part of Georgia’s production—silk manufacture. Women also served in a few businesses, most notably as the owners or managers of inns and taverns.

The experience of African and African American women in colonial Georgia was different from that of all other groups; most were enslaved. Slavery was forbidden in Trustee Georgia as inconsistent with the goals of the Trust and crown. Some colonists did use enslaved people illegally in this period, but the gender of those enslaved workers is not known. Many white colonists argued for changing the Trust policy to allow the use of slave labor, and the Trustees finally acquiesced in 1750. Over the next decades before the American Revolution (1775-83), the number of enslaved Africans grew, with males far outnumbering females.

In the early 1750s an enslaved woman cost between twenty-five and thirty-three pounds, about three pounds less than a male, although she could be more expensive if skilled in household work. Children were usually sold with their mothers. Most early enslaved women came from South Carolina, often brought by planters who acquired land grants in Georgia after the lifting of the slavery ban. By the middle of the 1760s the slave trade began to come directly to Georgia, and enslaved African women worked on Georgia soil. Like their men, enslaved women worked in the fields to plant and harvest. Some also took on household tasks; they were seamstresses, washerwomen, cooks, housekeepers, even hairdressers. Enslaved women also bore children. Occasionally women tried to escape their bondage by running away, although not as often as enslaved men.

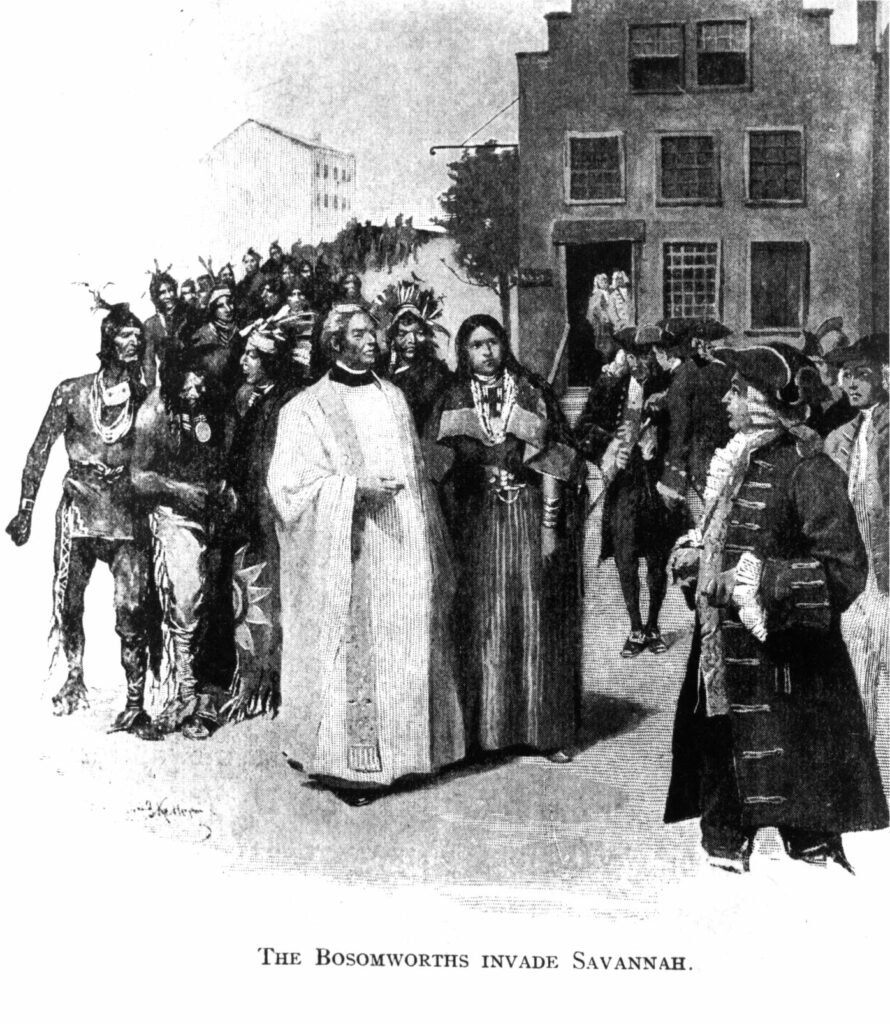

The women who appear most often in the records of colonial Georgia were those who in some way did not fit the normal expectations, such as the Italian silk winder Jane Mary Camuse and the Anglo-Indian interpreter and diplomat Mary Musgrove. Some of these women were considered “troublesome” by the Georgia government. Other women appear in the records for committing crimes, for behaving immorally, or simply for speaking their minds. Most colonial women in Georgia, however, remained anonymous, fulfilling their roles as wives, mothers, and servants, and thus contributing to the survival, stability, and growth of the colony.