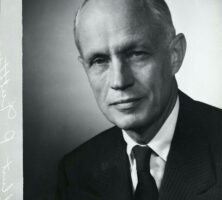

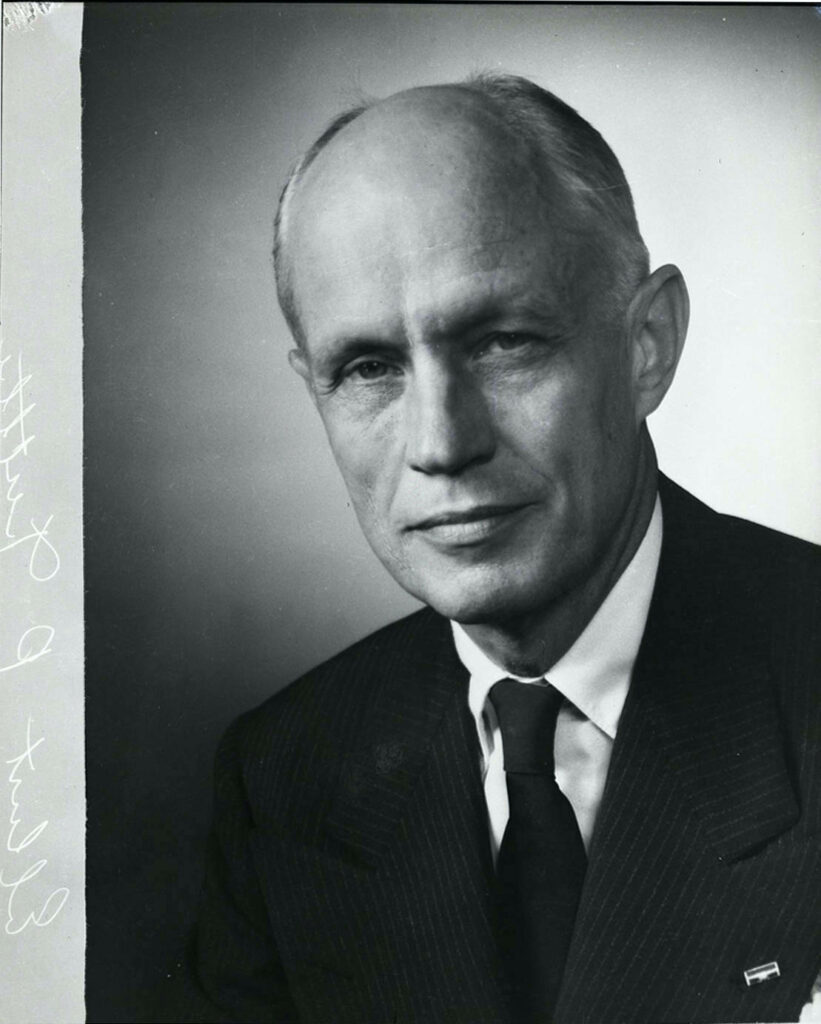

Elbert Parr Tuttle was a circuit court judge who exercised great influence during the civil rights era. U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him to the Atlanta-based Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1954, shortly after the historic Brown v. Board of Education decision by the Supreme Court opened the door to massive social, legal, and political change. Tuttle was a perfect jurist for the challenge: he possessed great personal courage, sound judgment, and a belief in common law development. He noted, “The law develops to meet changing needs… according to changes in our moral precepts.”

Tuttle was born in Pasadena, California, on July 17, 1897, and in 1906 he moved with his family to Hawaii, where his father, Guy Harmon Tuttle, had accepted a position as bookkeeper on a sugar plantation. Tuttle attended a multiracial school, Punahou Academy, in Honolulu, where he played football and ran cross-country. A dedicated athlete, he took up surfing and outrigger canoeing and, in college, skiing. After college he added polo and golf.

In 1914 Tuttle, who had skipped a grade, and his older brother, Malcolm, entered Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Tuttle was president of his senior class, and after graduation he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1918 as a “Flying Cadet” in the artillery’s observation corps. World War I (1917-18) ended while he was in training, and Second Lieutenant Tuttle joined the U.S. Army Reserve, maintaining continuous military service for the next thirty-two years.

In 1919 Tuttle took a job as a news reporter and editorial writer for the New York Evening World and various publications as he worked his way through law school at Cornell. During this period he developed his talent for writing and editing. This served him well after his appointment to the bench, as evidenced by the logic and clarity of his written opinions. Also in 1919 he married Sara Sutherland, who was his wife for more than sixty years. Tuttle excelled in law school, editing the law review and joining a number of honor societies. Graduating in 1923, he and his brother-in-law, William Sutherland, decided that Atlanta looked like an up-and-coming city and founded the firm of Sutherland, Tuttle, and Brennan there the same year.

Though he specialized mostly in tax litigation, Tuttle performed considerable pro bono work for clients who were unable to pay and, with the American Civil Liberties Union, handled a number of civil rights cases. He worked to get a new trial for a Black man convicted of raping a white woman and challenged a Georgia law that sent another African American to the chain gang for handing out Communist propaganda. A pro bono case in which he defended a young marine’s right to counsel led to the landmark Johnson v. Zerbst (1938) Supreme Court decision regarding indigent defense.

When America entered World War II (1941-45), Tuttle turned down a desk job and the rank of colonel. Believing that he should serve with the men he had commanded in his army reserve unit, he went on active combat duty with the 77th Infantry Division as a lieutenant colonel in a field artillery battalion. He served in the Pacific theater at Guam; the island of Leyte, Philippines; and Okinawa, Japan, and was almost killed on the Japanese island of Ie Shima in hand-to-hand combat when Japanese soldiers infiltrated his unit at night. He earned the Legion of Merit, Bronze Star, Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster, and Bronze Service Arrowhead. After the war he continued service as commanding general of the 108th Airborne Division (reserve), retiring as a brigadier general in 1950. In 1981 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

After he returned from the war, Tuttle resumed his law practice and his role as a community leader, becoming more involved with political affairs. He had allied himself with the Republican Party because he opposed the segregationist policies and practices of the Georgia Democratic Party. He came to know Governor Earl Warren of California during the 1948 presidential campaign, when Warren was Tom Dewey’s running mate. As one of Georgia’s leading Republicans, Tuttle led the effort to elect Eisenhower in 1952. In 1953 President Eisenhower appointed him general counsel and head of the legal division of the U.S. Treasury Department and a year later elevated him to the U.S. Court of Appeals (Fifth Circuit). Tuttle’s work with the Republican Party and with civil rights, which could have turned many of his associates against him, seemed not to affect his status as a civic leader. He worked with a variety of Atlanta civic and charitable groups, such as the Chamber of Commerce, Community Chest, Piedmont Hospital, Planning Council, Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University), Morehouse College, and Spelman College. He was president of the Atlanta Bar Association in 1948.

Tuttle’s call to the bench came a few months after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, which led to the integration of U.S. public schools. He recognized that the decision would precipitate a great social and legal upheaval, and that helped him decide to accept the challenge. He and the Fifth Circuit Court quickly became involved in civil rights cases. Tuttle heard Martin Luther King Jr.’s appeal challenging a district court order that prohibited meetings and demonstrations in Albany; James Meredith’s request to be admitted to the University of Mississippi; and Julian Bond’s request to be seated in the Georgia House of Representatives. He heard Gray v. Sanders (1963), which outlawed Georgia’s county unit system and ruled in three major congressional-district reapportionment decisions (Toombs v. Fortson, Wesberry v. Vandiver, Wesberry v. Sanders ). Throughout the 1960s he was involved in numerous voter registration, civil liberties, school desegregation, and jury and job discrimination cases. In 1961 he was appointed chief judge of the Fifth Circuit and impressed his colleagues with his ability to hear large numbers of cases and write decisions faster than most other judges.

Judge Tuttle and the other Fifth Circuit judges helped change the course of a nation concerning civil rights. They applied and expanded the Warren Court’s activist philosophy in their decisions. In 1968 Tuttle requested semiretirement as a senior judge and stepped down as chief judge. He maintained a heavy workload as he continued senior status with the creation of the new Eleventh Circuit in 1981. Tuttle died in Atlanta on June 23, 1996.