Georgia, uniquely situated among southern states on the eve of the Civil War (1861-65), played a vital part in the formation of the Confederacy. A geographic lynchpin that linked Atlantic seaboard and Deep South states, the “Empire State” was the second-largest state in area east of the Mississippi River (Virginia was larger until West Virginia broke away in 1861), and the second-largest Deep South state (only Texas was larger). In population, enslaved and free, Georgia was the largest in the Deep South. Both geographically and demographically, Georgia encompassed as much diversity as any other Confederate state, and these factors had an important impact on how the state experienced the war years and what it contributed to the Southern war effort.

Courtesy of Morris Museum of Art

Population

Georgia’s population passed 1 million residents for the first time in 1860. Census figures that year indicate that more than 591,000 of those residents (56 percent) were white, and nearly 466,000 (44 percent) were Black. These figures reflect a 16.7 percent increase in the state’s 1850 population, a somewhat slower growth rate than Georgia had seen in the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s, due largely to outmigration by Georgians headed west.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

In terms of geographical distribution, nearly 60 percent of the populace lived in the Black Belt region, a broad swath running diagonally through the state’s center from South Carolina toward the southwest along the Alabama and Florida line. The vast pine barrens or wiregrass region of southeastern Georgia was the state’s most sparsely populated area, with only 5.6 percent of the state’s total population; the narrow strip of six coastal counties had about the same percentage of the population as the southeastern counties, though concentrated in a far smaller area. The upcountry and mountain counties together claimed nearly a third of the populace.

Enslaved African Americans outnumbered whites in both the Black Belt and the coast (making up 55 percent in the former and 59 percent in the latter). About a fourth of the wiregrass and upcountry counties’ populace consisted of enslaved people, and only 13 percent of mountain residents were enslaved, with several of the northernmost counties claiming enslaved populations of less than 5 percent.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Like the rest of the South, Georgia remained overwhelmingly rural in the mid-nineteenth century, averaging a population density of fewer than 16 people per square mile. In 1860 nearly 8 percent of Georgians lived in towns or cities of more than 2,000 people, up from 4.6 percent in 1850. Savannah remained Georgia’s largest city, as it had always been, with the highest concentration of enslaved people (around 35 percent). With 22,292 residents, Savannah was nearly twice the size of Augusta, the second-largest city in the state, with 12,493 people. Columbus, with 9,621 residents, was only slightly larger than rapidly growing Atlanta, with 9,554. (Atlanta had nearly quadrupled in size since 1850 and would almost double in size by 1862; by 1880 it had become the state’s largest city.) Macon was the state’s fifth-largest city, with a population of 8,247. Enslaved African Americans made up roughly a third of all of these cities’ populations, except Atlanta, where only 1 in 5 residents were enslaved. Free Blacks made up a mere 0.3 percent of the state’s Black population in 1860, and they were concentrated largely in urban areas, especially Savannah and Augusta.

Nearly 99 percent of white Georgians in 1850 were American by birth; slightly more than three-fourths of those were born in Georgia. By 1860 newcomers to the state included an increasing number of northerners, attracted by business opportunities in growing cities like Atlanta. The largest foreign-born concentration was in Chatham County, where nearly a third of its free residents, primarily Irish laborers and a small but influential group of German Jews, were born abroad.

Class and Wealth

Georgia remained a sharply divided society in terms of wealth and resources, with a pronounced hierarchical social structure dictated by the institution of slavery. Although more than 60 percent of white families in the state did not hold people in slavery, the 37 percent who did, and especially the small tier of large planters, skewed the average to suggest that Georgia was among the wealthiest states in the Union. The per capita wealth of white Georgians in 1860, for example, was nearly double that of New Yorkers or Pennsylvanians. On average, slaveholders in the state owned property worth nearly five times that of a typical landholder in the North. Enslaved people in Georgia were worth more than $400 million in 1860, and accounted for at least half the state’s total wealth.

Courtesy of New York Historical Society

A mere 6 percent of white Georgians held nearly half the state’s property. They made up the planter class, generally defined as those who enslaved 20 or more people and whose plantations ranged from 200 to 500 improved (or farmable) acres. While the largest holdings in Georgia were smaller than those of planters in Mississippi or Louisiana (only 23 Georgia planters enslaved more than 200 people, and only one enslaved more than 500), a number of Georgia families still ranked among America’s richest citizens. Much of this concentration of wealth was on the Sea Islands, and yet the newly opened lands of western and southwestern Georgia, which had been frontier areas only a generation or so before, were home to an ever-increasing number of the state’s largest and most profitable plantations by 1860. Nearly 40 percent of the Black Belt’s enslaved population were located along the Flint River and the Alabama border.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Slaveholders who did not fall into the planter class but enslaved more than five individuals comprised 21 percent of free households; along with planters, they held approximately 90 percent of the state’s wealth, according to one estimate. Many of these slaveholders were professionals, including lawyers, politicians, and doctors, or businessmen who lived in towns or cities while still maintaining plantation operations nearby.

Nearly three-fourths of the state’s white population consisted of yeomen and the landless poor, who claimed less than 10 percent of Georgia’s wealth. The yeoman class included farmers who enslaved fewer than five people and, for the most part, fewer than 100 acres of improved land. Many such residents were concentrated in the less-productive mountain counties and the wiregrass region. These areas were also home to many dirt or subsistence farmers, who raised just enough to support their families but nothing of any commercial value. The number of landless whites increased over the antebellum period and made up nearly half of the white populace by 1860. Many of these were farm tenants, who made up as much as 40 percent of the agricultural workforce in some of the state’s more marginalized counties. Others were sons waiting to inherit land from their fathers, laborers who drifted from one county to another looking for work, or overseers hired to manage large plantations.

Agriculture

Nearly 75 percent of Georgia’s white male populace between the ages of twenty and seventy, and more than 90 percent of its enslaved populace were directly engaged in agricultural pursuits in 1860, and as noted above, the vast majority of the state’s productivity and wealth grew from its plantation economy. Cotton remained king. Georgia had led the world in cotton production during the first boom in the 1820s, with 150,000 bales in 1826; later slumps led to some agricultural diversification. Nevertheless, Georgians raised 500,000 bales in 1850, second only to Alabama, and nearly 702,000 bales in 1860, behind Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. All of these states were beneficiaries of another boom in cotton prices in the late 1850s. The vast majority of cotton production in Georgia fell within the Black Belt (4 of every 5 bales were produced there), although the upcountry and coastal islands were also steady producers.

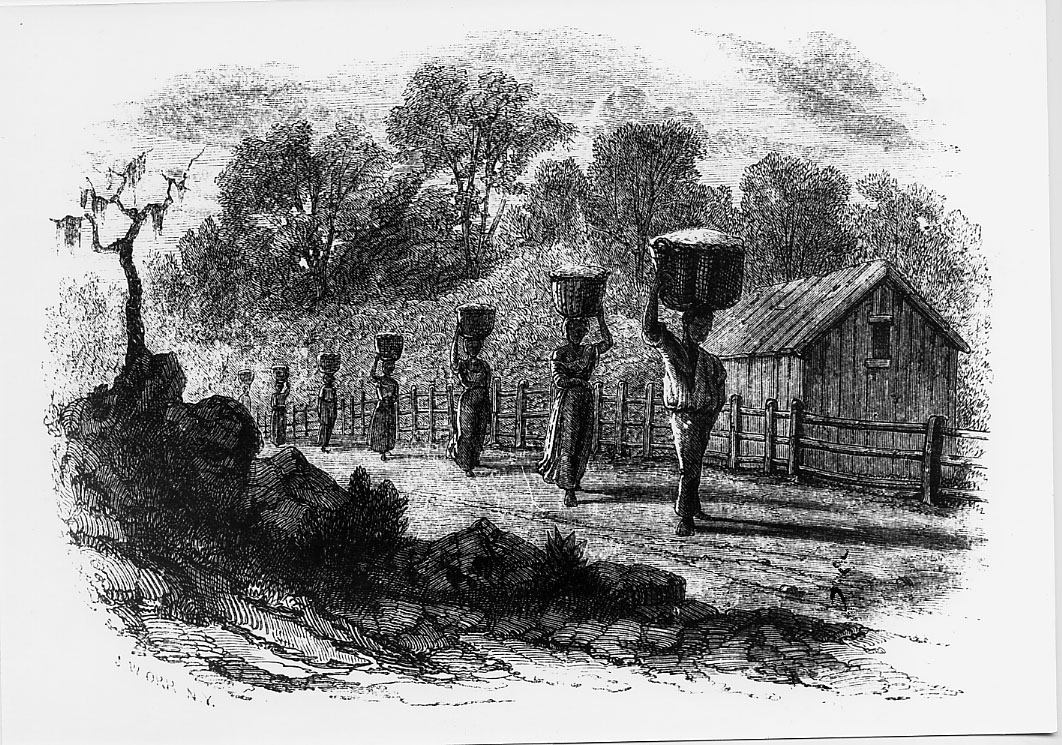

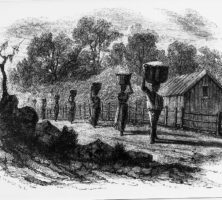

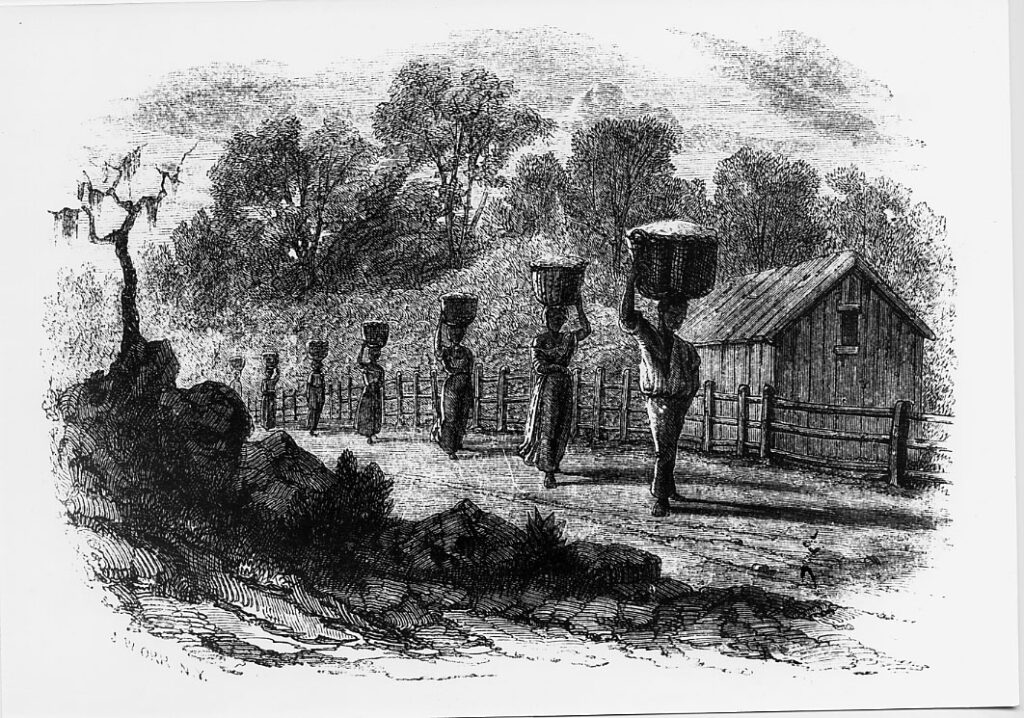

From Harper's New Monthly, March 1854

Corn, claiming 40 percent of the state’s cultivated land, rivaled cotton as an agricultural commodity and was the mainstay of smaller farmers outside the Black Belt. Much of that corn was grown to feed hogs, with more than 2 million raised throughout the state in 1860. As a result, pork was the most-consumed meat by Georgians, Black and white, as was true for most antebellum southerners. Hogs and other livestock were raised in the mountains and in the wiregrass and sold to plantation markets as the most viable cash commodity produced by small farmers.

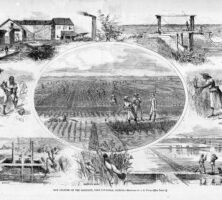

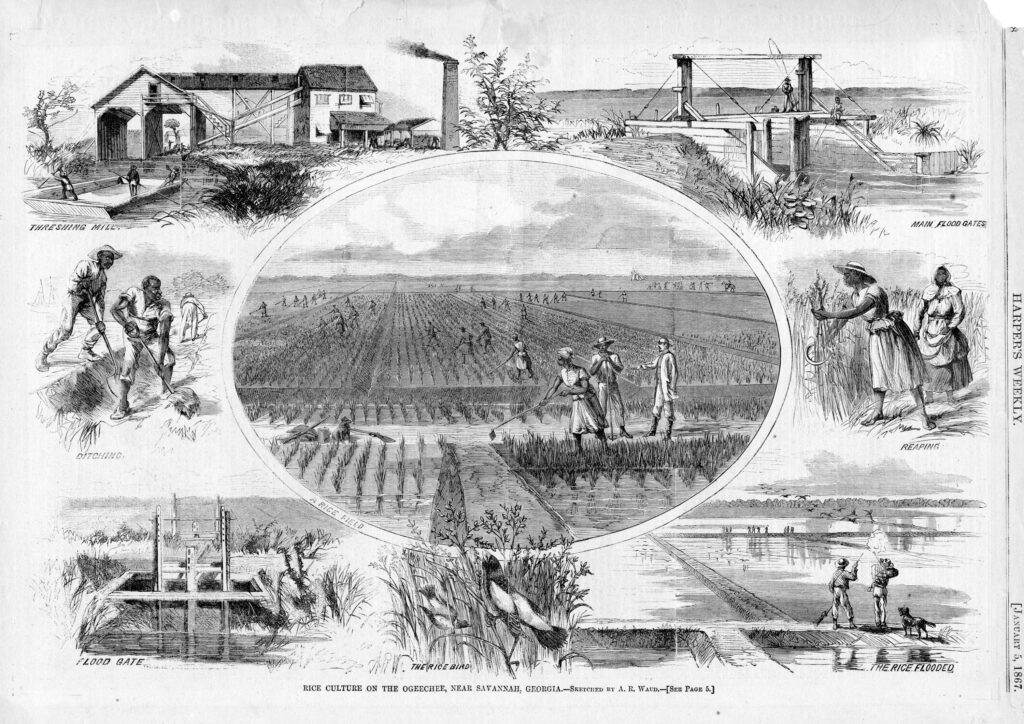

From Harper's Weekly

On the coast, rice continued to be among the most lucrative of crops, and Georgia trailed only South Carolina as the nation’s largest rice producer. After a lag of several decades, rice made a dramatic comeback in the late antebellum period, moving from 39 million pounds produced in 1850 to more than 52.5 million pounds ten years later. A number of secondary crops, including tobacco, wheat and oats, and sweet potatoes, were grown in abundance throughout the state; more sweet potatoes were grown in Georgia than anywhere else in the world in 1860.

Industry

The most pervasive forms of industry in late antebellum Georgia remained those most closely tied to agriculture, including the gristmills and sawmills that produced the flour, cornmeal, and timber consumed both locally and in ever-widening markets within the state. The combined value of flour and meal totaled more than $4.5 million, according to the 1860 census, more than any other manufactured product in the state.

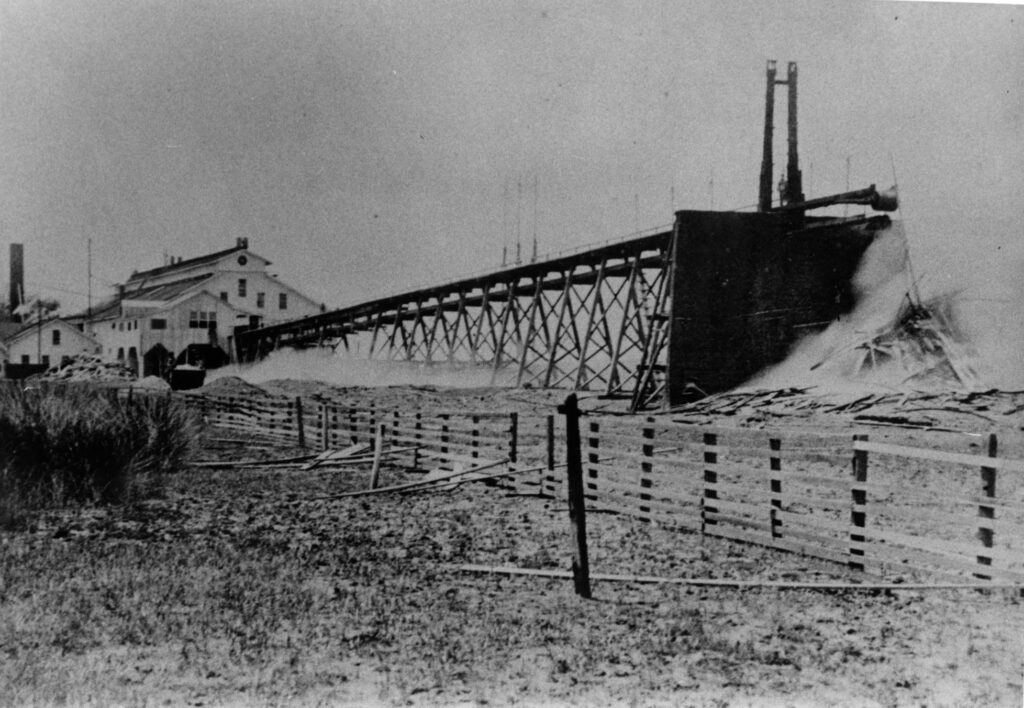

Image from Neal Wellons

Southerners’ campaign to bring cotton mills to the cotton fields, rather than sending their cotton off to New England, began in the 1810s, and early efforts at building textile mills in Georgia took place in the 1820s and 1830s. But it was only in the 1850s that the industry came of age, fueled both by the cotton boom of that decade and by more efficient applications of steam and water power in fall-line cities like Augusta, Columbus, and Macon, as well as in smaller communities like Athens, Roswell, and Sparta. In 1860 Georgia led the South in the number of textile workers, with 2,800 (more than half of them female) employed in thirty-three mills.

The lumber industry also experienced a boom in the 1850s, with pine and cypress products accounting for an annual worth of $2.4 million. In 1860 sawmills employed 16 percent of the state’s industrial workforce, most of which was concentrated in southeastern Georgia’s pine barrens and coastal counties. Savannah was the beneficiary of much of this production and had emerged by 1860 as one of the nation’s most active market and production centers, with sawmills, lumberyards, and a thriving export trade to England. Brunswick and Darien were secondary ports fueled primarily by timber floated downriver for processing there. Naval stores operations and turpentine distilleries were also driven by the state’s pine forests. In the mountains, marble quarries and small-scale mining enterprises of iron, copper, and coal were under way, though they became significant parts of the state’s industrial output only after the war.

Courtesy of Coastal Georgia Historical Society.

Enslaved laborers made up much of the state’s industrial workforce. Many were hired by companies on annual contracts to work in mines, sawmills, railroad construction, and other enterprises, both urban and rural. Only the textile industry resisted opportunities to employ captive laborers, and it was the focus of an ongoing debate as to the benefits or detriments of putting enslaved workers into factories. The 1860 census indicates that 5 percent of Georgia’s enslaved population spent the majority of their time laboring in industry rather than agriculture.

Among the most important developments that would shape the war in Georgia was the dramatic expansion of railroad tracks in the state during the 1840s and 1850s. By 1860 the state had the most extensive system of rail lines in the Deep South and was second only to Virginia in the South as a whole. Eighteen railroad companies had constructed 1,400 miles of track, at a cost of more than $26 million in private and public funding. These lines were vital to the state’s economic and industrial expansion and had much to do with driving Atlanta’s rapid growth as well as its strategic importance during the war.