Between 1805 and 1833, the state of Georgia conducted eight land lotteries (one each in 1805, 1807, 1820, 1821, 1827, and 1833 and two in 1832) in which public lands in the interior of the state were dispersed to small yeoman farmers (i.e., farmers who cultivate their own land) based on a system of eligibility and chance. During the twenty-eight years in which the lottery operated, Georgia sold approximately three-quarters of the state to about 100,000 families and individuals for minuscule amounts of money.

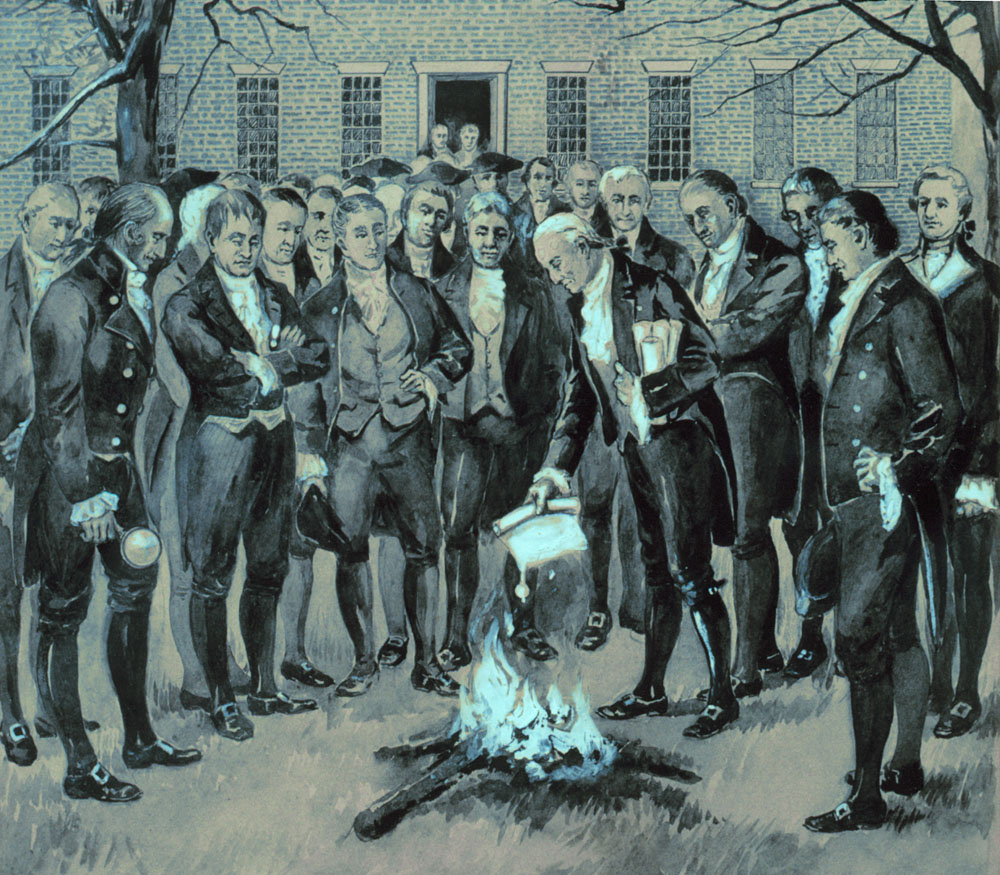

Artwork by George I. Parrish Jr. Courtesy of Cindy Parrish, Maryville,TN

As a colony, Georgia was controlled by an elite group of aristocratic planters. Rice and indigo thrived in the coastal region around Augusta and Savannah, allowing a few men to gain land, enslave people, and accumulate wealth while leaving the majority of the white population poor and politically weak. The turmoil of the Revolutionary War (1775-83) and the British occupation of Savannah and Augusta drastically affected the plantation economy, decreasing the political and economic power of the colonial elite and increasing the influence of the small yeoman planter. The Georgia Constitution of 1777, which reflected the idea of the common man controlling the government, embraced this power shift.

An increase in the demand for land by common farmers spurred westward migration. After the Revolution, Georgia claimed territory as far west as the Mississippi River. This enormous region allowed the state government to pay those who had fought against the British with land grants. Heads of households in Georgia could receive 200 acres of land or more if the household included family members or enslaved people. Yet by the 1780s speculators and legislators were authorizing more land for homesteading than was available. The speculative fever came to an end in 1795, when the legislature passed the Yazoo Act, which sold almost 60 percent of the land in present-day Alabama and Mississippi to four companies for $500,000. The four companies and their allies engaged in bribery to gain the contract, and because of this corruption, Georgia ended the unregulated system of land speculation in favor of a lottery system to dispose of public lands.

The first land lottery, held in 1805, was authorized by the legislature on May 11, 1803, and involved 490-acre plots in Wayne County and 202.5-acre plots in Baldwin and Wilkinson counties. For a fee of four cents an acre, common Georgians could amass a sizeable land holding. In each lottery eligible participants (families consisting of a husband, wife, and at least one child; every widow with children; and every white male who had lived in Georgia for at least one year) applied to the state, which entered their names on sheets of paper deposited in one drum while the lot numbers of the eligible properties were placed in another drum. The number of times a participant’s name was entered into the first drum was dictated by age, marital status, war service, successful participation in previous lotteries, and years of Georgia residence.

The other seven land lotteries operated on the same principles as the first. For an average price of seven cents an acre, Georgians gradually moved westward onto land previously owned by Native Americans. The acquisition of this land intensified after Georgia and the U.S. government signed the Compact of 1802. In that compact Georgia agreed to relinquish claims to Alabama and Mississippi; in exchange, the federal government paid the state $1.25 million, which was used to settle disputed Yazoo land claims, and promised to remove the remaining Creek Indians from Georgia’s borders. Andrew Jackson’s victory over the Creeks during the War of 1812 (1812-15) helped effectively to eliminate the Creeks from the state. The 1805, 1807, 1820, 1821, and 1827 lotteries involved Creek lands; the 1820 lottery involved Creek and Cherokee lands; and the two 1832 lotteries and one in 1833 involved Cherokee lands. Beginning in 1832, Cherokee territory in present-day Bartow, Cherokee, Cobb, Floyd, Forsyth, Gilmer, Lumpkin, Murray, Paulding, and Union counties entered into the lottery system and was dispersed to thousands of Georgia families. A separate lottery was held in 1832 to distribute forty-acre “gold districts” for $10 each in the same Cherokee area.

The land acquired on the frontier by the lotteries was originally used for tobacco cultivation, but with the introduction of cotton and the innovation of the cotton gin, agriculture shifted to large-scale cotton production. The need for labor to toil on these plantations across the state called for more and more enslaved laborers; by 1820, enslaved African Americns made up 44 percent of Georgia’s population. Therefore, the land lottery not only increased the landholdings of common Georgians but also increased their ability to become slaveholders and enter the planter class.

The final land lottery was conducted in 1833 to dispense with the remaining territory from the 1832 lotteries. But the system had dramatically changed Georgia so that aristocrats no longer held political and economic domination over the state as they had before the Revolution. On average, Georgia planters held less land than their contemporaries in other southern states, reflecting the power shift from large landholding aristocrats to yeoman farmers.