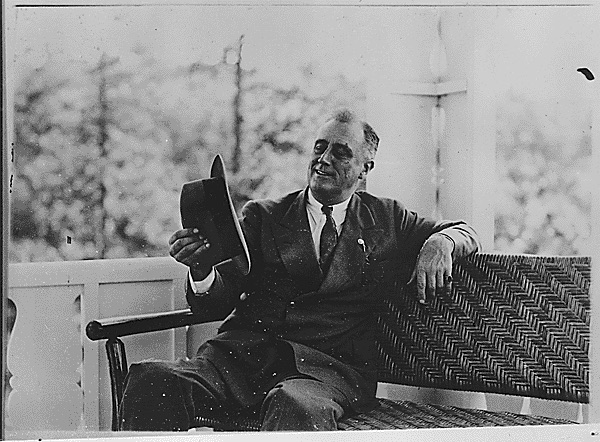

Georgia was helped perhaps as much as any state by the New Deal, which brought advances in rural electrification, education, health care, housing, and highway construction. The New Deal also had a particularly personal connection to Georgia; Warm Springs was U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s southern White House, where he met and worked with many different Georgians. From the 1920s and throughout the Great Depression, he saw firsthand the poverty and disease from which the state was suffering, and he approached its problems much as a Georgia farmer-politician would. At the same time, the state’s conservative politicians, voicing fears that the New Deal would destroy traditional ways of life, fought tooth and nail against what they saw as government meddling in local affairs, and many of Georgia’s political battles of the 1930s revolved around opposition to new federal programs.

Roosevelt’s New Deal

After he was stricken with polio, Roosevelt began visiting the therapeutic waters of Warm Springs in the mid-1920s to strengthen his paralyzed legs. He established the Warm Springs Foundation (later the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation), and he became actively involved in the local community. Through Warm Springs, Roosevelt began to study the connections between Georgia’s difficult agricultural conditions and its social and educational problems. His New Deal programs, begun immediately upon his inauguration in 1933 and aimed first at economic recovery, would ultimately address the nation’s and Georgia’s social conditions as well.

By the time Roosevelt came to office, Georgia’s farmers, in desperate straits from years of depression and low cotton prices, were echoing the demands of the 1890s Populists for government intervention in agricultural affairs. A New Deal relief worker along the Georgia coast reported, “The school teachers, ministers, relief officials, and recipients alike stated that . . . if emergency aid had not been provided a revolution would have resulted.” Within a year 20 percent of Georgia’s urban residents were receiving some kind of federal relief, as were more than 15 percent of those living in the Piedmont region and along the coast.

During the early years of the depression, before Roosevelt took office, churches, the Salvation Army, and a few local governments offered limited assistance to the poor. State aid was negligible. Between 1933 and 1940, however, the New Deal brought $250 million to Georgia and established a series of agencies that offered a broad range of public works programs, including the construction of libraries, roads, schools, parks, hospitals, airports, and public housing projects.

As a way of raising long-depressed cotton prices, the Agricultural Adjustment Act, established during Roosevelt’s first 100 days in office, paid farmers to plant less cotton as a means of restricting the supply and driving up the price. The Bankhead Cotton Control Act of 1934 controlled cotton production even more tightly. In 1929, at the start of the depression, farmers had received 16.78 cents a pound for cotton. By 1932 cotton had fallen to 6.52 cents a pound. By setting quotas to limit the acreage of farmland planted with cotton, the price quickly rose, and by 1936 it had reached 12.36 cents a pound. Prices fell again before new programs late in the 1930s helped rescue the growers. Roosevelt’s intention was to turn Georgia’s struggling, debt-ridden tenant farmers and sharecroppers into self-supporting small farmers. In economic terms, however, the small landowner actually gained less from the federal programs than did planters who owned larger and more mechanized farms.

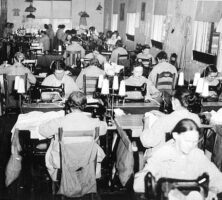

New Deal programs also provided work relief for Georgia’s rural poor through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the National Youth Administration (NYA). Greene County, in Georgia’s Piedmont region, became an experimental site for the Unified Farm Program, where federal, state, and local officials worked to provide farmers with loans to move to improved farms and homes. Such programs helped only a fraction of the state’s poor and landless, but to the state’s rural population—its African American and white farmers and sharecroppers—for whom the federal government had been a distant entity, the New Deal became a source of recovery they could see in their own communities. The New Deal inaugurated the first urban public housing, called Techwood Homes, including the first federal slum clearance project, undertaken in Atlanta in 1935.

Critics claimed New Deal initiatives destroyed southern institutions through unwarranted and unconstitutional federal imposition upon state jurisdiction, particularly in the social arena and in cultural life. Wealthy landowners complained that New Deal support for improved pay would lead to labor shortages, because tenant farmers, wage hands, and sharecroppers would refuse to work for local planters if they could earn the higher wages paid by the federal government. Urban projects also led to protests against government interference in local communities.

African Americans’ New Deal

Among the major achievements of New Deal programs in Georgia was the work of the NYA. Pushed and guided by the first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, the NYA worked across racial lines to encourage the state’s young women and African American teenagers of both sexes to pursue an education. Broad in scope and remarkably egalitarian, the NYA offered hard-to-find jobs to students who needed financial help to stay in school. Black and white administrators worked to fund students in high school, vocation training programs, and college. The American Youth Commission called Georgia’s NYA program the best in the nation, largely because it benefited from the particular interest shown by Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary McLeod Bethune (director of the Division of Negro Affairs of the NYA) at the national level.

By the end of 1935 Georgia’s NYA had provided work for more than 2,000 students, both Black and white, at fifty colleges and universities around the state. In fact, Georgia was second only to Texas, where future U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson directed the NYA program, in the amount of aid its students received. In return for the assistance, students in NYA programs constructed hundreds of buildings around the state and remodeled old schools and public facilities.

President Roosevelt balanced the interests of conservative, southern Democrats, to whom he owed much of his political power within the national party, with his desire to improve the conditions of Georgia’s African American population, especially in education and labor policy. While federal policy in the 1930s did little to advance the cause of civil rights, Roosevelt himself, as well as members of his administration, worked in local communities to improve opportunities for Blacks. Soon after his inauguration Roosevelt planned a modern school building for African American children of the Warm Springs district, enlisting two New Deal agencies, the WPA and the Public Works Administration, to help in its construction.

Nevertheless, federal programs bowed to local customs, and racial discrimination affected the distribution of relief work throughout the New Deal era. In Greene County through the early New Deal years, Civil Works Administration projects hired twice as many whites as Blacks and paid whites, on average, 75 percent more. But the active engagement of federal officials in solving Georgia’s problems established an atmosphere that made it easier for African Americans to advance their claims for full citizenship. The New Deal brought a spirit of egalitarianism that, for the first time since Reconstruction, aided civil rights and economic activism.

Talmadge’s Opposition

Roosevelt’s new federal programs required the cooperation of state governments and were, therefore, slowed considerably by Eugene Talmadge, elected governor of Georgia in 1932. Having earned the trust of farmers as state agriculture commissioner, Talmadge consciously courted rural voters through lively political rallies in the state’s small towns and countryside. His white-supremacist, pro-evangelical, and anti-corporate tirades had great grassroots appeal and earned him the long-term loyalty of his largely rural constituency. In Talmadge the New Deal found one of its most vigorous opponents.

On the stump, Talmadge referred to himself as “a real dirt farmer,” but according to historian William F. Holmes, Talmadge had limited knowledge of the difficulties faced by Georgia’s farmers. “He believed that by hard work and thrift alone a person could master his own fate,” Holmes writes. “He opposed programs calling for greater government spending and economic regulation. Such views, especially during the Great Depression, ignored the plight of tenant farmers as well as many landowners.”

In Talmadge’s two terms as governor (1933-37), Georgia state government subverted many of the early New Deal programs. Conflicts developed immediately concerning federal relief programs. Talmadge wanted the labor paid on public works projects to be set in accord with Georgia’s prevailing low wages, or even lower, so workers would have incentive to return to work for private employers. Appealing to white supremacy, he criticized New Deal programs that paid Black workers as much as whites. To Talmadge, the New Deal was “a combination of 'wet nursin,’ frenzied finance and plain damn foolishness.” He courted the rural poor but allied himself with conservative business interests by opposing government regulation, welfare spending, and the interests of organized labor.

After his reelection in 1934, Talmadge intensified his attacks on Roosevelt and warned of “Communist” tendencies in the New Deal. In spite of Talmadge’s popularity, opposition coalesced after Talmadge vetoed measures that would have enabled Georgia to participate in the newly created Social Security Administration.

In Georgia’s 1936 Democratic primary, opposition to the New Deal became a key issue. By state law Talmadge could not run for a third term as governor, so he entered the U.S. Senate race against incumbent Richard B. Russell Jr., a firm New Deal supporter. Talmadge endorsed Charles D. Redwine, president of the state senate, to succeed him as governor. House Speaker E. D. Rivers was the most avid pro–New Deal gubernatorial candidate. The electorate polarized into two camps, but the New Dealers, Russell and Rivers, each polled about 60 percent, demonstrating Georgians’ desire to benefit from the federal funds flowing toward health facilities, highway construction, and rural electrification.

Later New Deal Politics

As governor, Rivers worked with the state legislature to enact measures that enabled Georgia to receive federal funds for dependent children, the aged, and the blind, and to participate in federal unemployment and workers’ compensation. Within four years Georgia led the nation in the number of rural housing projects and in the amount of money per capita spent on urban housing, and led the nation as well in the number of Rural Electrification Administration cooperatives. State appropriations to education increased significantly.

But Rivers failed to keep the public informed of the tax increases needed to cover the costs of these programs, and he narrowly won reelection in 1938. During his second term state revenues slipped, and the legislature refused his requests for increased taxation. Rivers ended up cutting the state budget he had promoted, and reports of corruption within his administration cost him public support.

As the 1938 elections approached, Roosevelt tried to strengthen his support among southern Democrats by actively campaigning for candidates who remained loyal to his New Deal programs and purging those southern Democrats in Congress who had turned against the New Deal. Up to 1937 U.S. senator Walter F. George had supported most of the major New Deal programs, but he joined a coalition of Republicans and conservative Democrats who resisted further reforms. As historian J. William Harris observes, “George and like-minded southerners were happy to support legislation, like price supports, that benefited cotton planters, but they opposed laws that would interfere with their control of labor.”

In the 1938 Senate campaign, George ran for reelection against Talmadge and Lawrence Camp, a former state legislator and federal district attorney who was running as a strong pro-Roosevelt New Dealer. In a speech in Barnesville in August 1938, Roosevelt cited the recently completed Report on Economic Conditions of the South, which called the South “the Nation’s No. 1 economic problem,” and he asked voters to cast their ballots for Camp. In spite of Roosevelt’s endorsement, Camp ran a distant third, and George was reelected, signaling the conservative turn the state was taking by the late 1930s toward stricter economic measures and away from the New Deal’s social and economic planning. The infusion of New Deal funds would soon be supplanted, in any case, by the economic stimulus of a wartime economy, with the entry of the United States into World War II (1941-45).

“Between the Populist uprising and World War II,” William F. Holmes writes, “the most meaningful attempts to bring social and economic reforms to Georgia occurred under the New Deal.” Even though Governor Talmadge fought against the New Deal for its first four years and Governor Rivers could not continue to fund new measures, the New Deal had a substantial impact on Georgia. Although the state continued to suffer throughout the depression from social and agricultural problems, as well as racial and economic inequalities, the New Deal’s welfare and public works programs offered many Georgians a needed measure of relief and a greater sense of dignity.