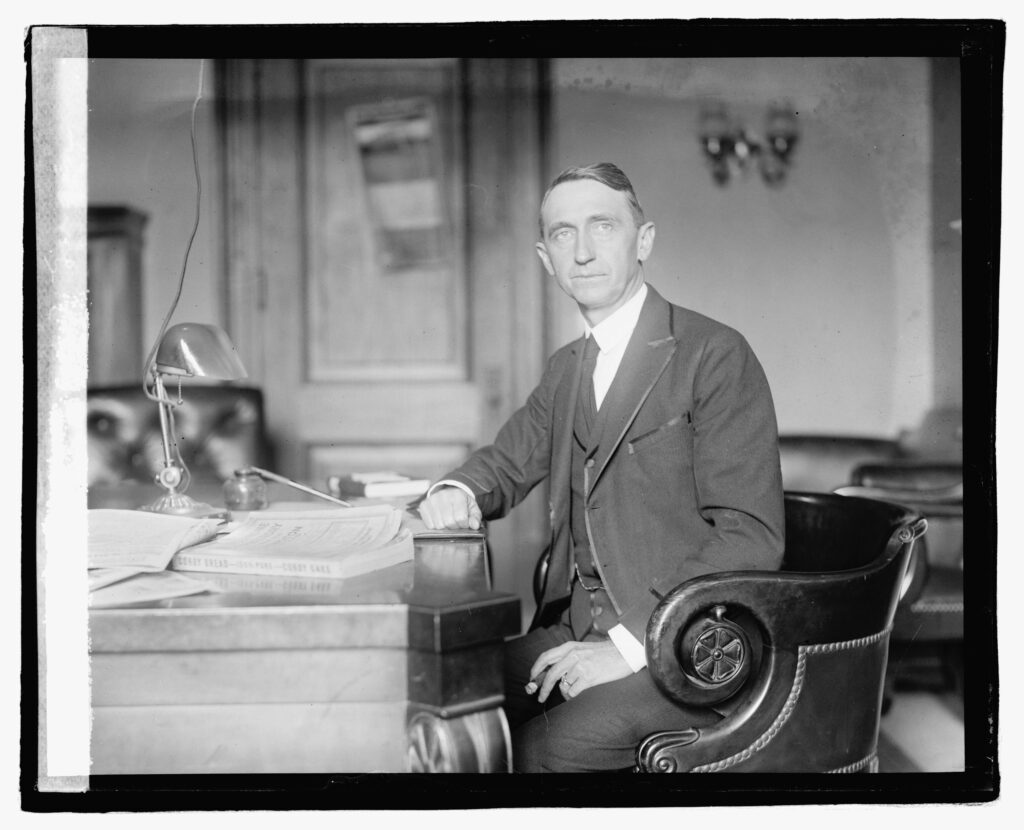

Walter F. George was one of Georgia’s longest-serving members of the U.S. Senate (1922-57), and he distinguished himself in terms of his diplomatic influence during World War II (1941-45) and the early years of the cold war.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

While George opposed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s nomination for president in 1932, he supported several of his early New Deal programs. He broke with Roosevelt in his second presidential term, however, particularly over his attempts to pack the U.S. Supreme Court with justices favorable to the New Deal. This led to Roosevelt openly supporting George’s opponent in the 1938 senatorial election, but George easily won renomination and election. In 1941 George again supported Roosevelt, urging Congress to pass legislation allowing the military to prepare for conflict in case the United States was drawn into World War II. He also supported Roosevelt’s dream—the United Nations Charter of 1945.

Early Life

Walter Franklin George was born in Webster County on January 29, 1878, to Sarah Stapleton and Robert Theodoric George. His parents were sharecroppers. He attended Mercer University in Macon and graduated in 1900. A year later he graduated from Mercer’s law school, passed the bar, and set up a law practice in Vienna, in Dooly County. George went on to hold various positions, including a superior court judgeship for the Cordele judicial circuit from 1912 to 1917 and a Georgia Supreme Court judgeship from 1917 until 1922. He married Lucy Heard in 1903, and they had two children, Heard Franklin and Marcus.

Political Career

When U.S. senator Thomas E. Watson died in 1922, George resigned from the court to run for the vacant seat. He won the special election to finish Watson’s term (although Rebecca Latimer Felton sat in the Senate for one day, the first woman to do so). George assumed the office on November 7, 1922, and held it for the next thirty-five years.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

During the 1920s George, a Democrat, tended to vote much like his fellow senators from the South—conservatively. He supported prohibition and opposed civil rights for African Americans, even voting against antilynching measures. He was a strong supporter of large corporations, particularly those based in Georgia, like the Coca-Cola Company and Georgia Power Company.

In 1928 Georgia’s congressional delegation selected George as their candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination. (Al Smith from New York received the national nomination but was soundly defeated by Republican candidate Herbert Hoover.) Even though George was never a serious candidate for the nomination, it was clear that he was very popular among his fellow Georgians.

The stock market crash of 1929 ushered in the Great Depression of the 1930s, and with it a new era in American politics. Still very conservative, George opposed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s nomination for president in 1932. Although never a strong proponent of the New Deal (and certainly not to the degree that his fellow senator Richard B. Russell Jr. was), George did support some programs that he saw as beneficial to Georgia—primarily the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Agricultural Adjustment Act.

George found far more to oppose during Roosevelt’s second term, however, including rigorous regulation of utility companies, the Wealth Tax Act, and Roosevelt’s attempt to pack the U.S. Supreme Court with justices favorable to his New Deal policies. Roosevelt—who considered Georgia his “second home,” given the time he spent at Warm Springs —undertook to actively try and unseat George. In a famous speech delivered in Barnesville on August 11, 1938, Roosevelt praised George for his service and acknowledged his intelligence and honor but urged voters to choose George’s opponent in the upcoming Democratic primary. George shook the president’s hand and accepted the challenge. George easily won renomination for his senate seat and, with the Democratic Party firmly in control of Georgia, easily won reelection also.

George and Roosevelt were in greater agreement on foreign affairs. In the 1940s, as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and then of the Senate Finance Committee, George supported Roosevelt’s efforts at military preparedness, including Lend-Lease aid to Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, already at war, and American defensive build-up in response to the threat posed by Japanese and German militarism. Once the United States entered World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, George embraced the president’s vigorous prosecution of the war, and even reversed his previous opposition to an international agency designed to keep peace by supporting ratification of the United Nations Charter in 1945.

With the emergence of the cold war during the late 1940s and 1950s, George continued to support America’s foreign policy, especially under Republican president Dwight D. Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, a close friend of George’s. In 1955 George proposed a summit meeting of the United States and its allies with the Soviet Union, which would have been the first since the end of World War II. Although the meeting never took place, George’s bipartisan support won him much acclaim from his fellow congressmen.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

On the domestic front, George and his fellow southern congressmen staunchly opposed civil rights. George’s office became a meeting place for southern senators to plot opposition strategy to the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, which declared the segregation of schools to be unconstitutional. Even though he strongly opposed integration, George was less vocal about it than Senator Russell or his brash young opponent in the 1956 election, Herman Talmadge.

Talmadge had the state political machinery built by his father, Eugene Talmadge, firmly behind him, and despite his seniority and leadership in the Senate (he served as president pro tempore in 1955 and 1956), George realized he was not likely to withstand the Talmadge challenge and declined to run for reelection. George’s service to the country was not completely done; he served President Eisenhower as a special foreign policy advisor and was appointed U.S. ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, a position he held only briefly before dying of heart problems on August 4, 1957. He was buried in Vienna.

Lake Walter F. George, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers lake near Fort Gaines, is named in his honor. In 1947 Mercer University named its law school the Walter F. George School of Law to honor their noted alumnus, and created a foundation in his name that helps fund students dedicated to careers in public service.