In 1907 Georgia became the first state in the South to pass a statewide ban on the production, transportation, and sale of alcohol. Prohibition in Georgia lasted until 1935, two years after the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment and the end of national prohibition (1920-33).

Early Efforts

Though prohibition would not be achieved until the early twentieth century, efforts to restrict drinking were undertaken soon after alcohol first appeared in the colony. To curb public drunkenness among both colonists and Native Americans, the Trustees issued a decree forbidding the sale of strong liquor in 1735. However, that initial act was overturned just seven years later amid mounting protest from merchants who claimed that it was harmful to the colony’s trade.

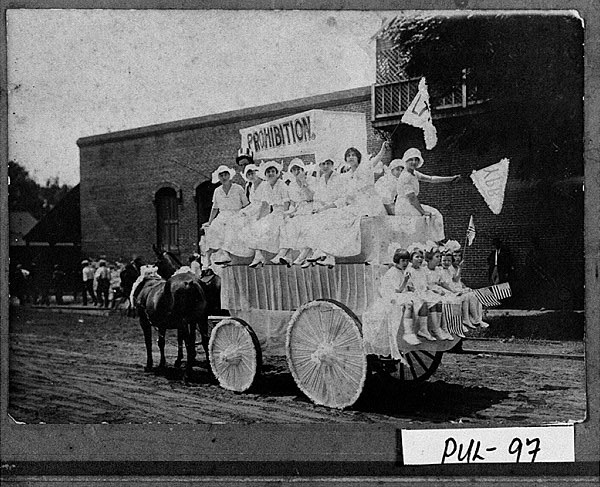

Temperance advocates continued their efforts with limited success in the early nineteenth century. Evangelical Protestants established the Georgia State Temperance Society in 1828, but the organization dissolved after adopting a teetotal pledge in 1836, and successor organizations struggled to gain momentum for their cause. Reformers enjoyed modest success in the 1870s with a series of legislative victories that included the elimination of alcohol sales on election days, the imposition of a twenty-five-dollar annual state tax on all liquor dealers, and the prohibition of liquor consumption in gambling establishments. Still, it was not until the 1880s, when the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) came to Georgia, that reformers enjoyed the support of a formidable statewide organization.

At the behest of the WCTU’s Georgia chapter, William J. Northen, of Hancock County, presented a local option law to the Georgia legislature in 1881. The proposed bill granted localities the right to vote for or against the sale of liquor after one-tenth of registered voters in a county signed a petition requesting a special election. Proponents claimed that prohibition would reduce crime and immoral behavior in urban areas while easing the financial burden on the families of those who overindulged. Support was hardly universal, however. Commercial shipping centers like Savannah, Augusta, and Brunswick were too financially invested in the liquor trade to support prohibition, and critics elsewhere maintained that existing licensing fees provided sufficient deterrence.

Nevertheless, after four years of false starts, the Georgia legislature passed the General Local Option Liquor Law in 1885. Though it did not prohibit the manufacture or sale of local wines and ciders or of medicinal or sacramental alcohol, the law did allow voters to prohibit the sale of liquor at the local level. While many counties immediately voted to go “dry,” success was short-lived in urban counties, which quickly reversed course after seeing no significant reduction in crime as advocates had promised. This setback only motivated Prohibitionists to refocus their energies on passing a statewide alcohol ban.

Statewide Prohibition Mandate

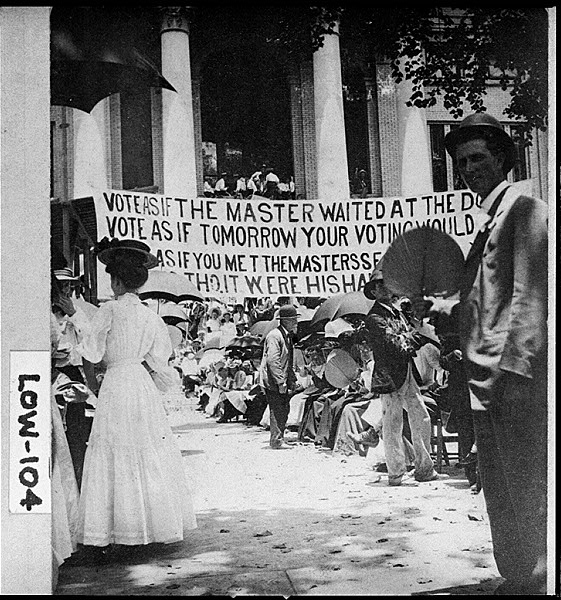

By the turn of the twentieth century, Atlanta had a prosperous African American community and many Black-owned businesses. During the 1880s evangelicals even courted Black voters, many of whom viewed prohibition as an opportunity to gain acceptance in white society. This tenuous alliance broke down as southern states, including Georgia, began implementing Jim Crow statutes to segregate public spaces and disenfranchise Black voters. As racial discrimination was codified into law, white prohibition supporters leveraged growing unrest to advance their agenda.

The Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906 provides a case in point. In the months before that conflagration, the city’s newspapers had stoked racial tensions by running dozens of articles that warned against social disorder, attributing Atlanta’s rising crime rates to drunkenness amongst the city’s working class African American men. The gubernatorial race of 1906, which pitted Hoke Smith, former publisher of the Atlanta Journal, against Clark Howell, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, only further inflamed passions, as both men campaigned on platforms that emphasized their commitment to white supremacy. Tensions reached a boiling point that September, when city papers ran a series of incendiary stories describing alleged assaults of white women by Black men. Though none of the stories were ever substantiated, they unleashed a paroxysm of violence among white Atlantans that raged for three days and ultimately claimed the lives of dozens of Black citizens.

Prohibitionists pressed their case in the wake of the Atlanta Race Riot and the General Assembly passed a statewide prohibition bill on August 6, 1907. Georgia was the first southern state to go dry, but others soon followed suit, and by 1915, eight states in the region had enacted statewide prohibition.

Legislative Loopholes and Repeal

Supporters cheered the bill’s passage, but it soon became evident that loopholes were limiting its effectiveness. Private locker clubs frequented by the wealthy escaped closure by serving alcohol only to members, and near-beer saloons served low-alcohol content beverages to circumvent the law. Under political pressure, Governor John Slaton called a special legislative session in the fall of 1915 to eliminate the locker-club provision, ban mail advertisements for alcohol, and prohibit the so-called jug train that shipped alcohol into dry locales.

On June 26, 1918, Georgia ratified the Eighteenth Amendment, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors in the United States. Congress certified the amendment’s ratification the following year, and prohibition took effect in January 1920. Thirst for strong drink never abated, however, and criminal organizations, which formed to satisfy unmet demand, were among the amendment’s greatest beneficiaries. For this reason, Georgians, like many Americans, grew frustrated with prohibition and later lobbied for repeal. The Twenty-first Amendment, repealing national prohibition, was ratified on December 5, 1933, though Georgia was one of eight states never to consider the amendment.

Ratification only emboldened prohibition’s critics in Georgia, many of whom claimed that the state could not afford to remain dry. By the early 1930s, the Great Depression had taken a toll on the state’s coffers, and the prospect of statewide repeal stood to produce a windfall of new tax revenue.

Facing a dire economy and sustained advocacy from prohibition’s critics, the Georgia legislature approved the Alcoholic Beverage Control Act on March 22, 1935. The act called for a statewide referendum on the issue of repeal and tasked the State Revenue Commission with drafting new regulations to govern the sale and distribution of alcohol. Governor E. D. Rivers effectively nullified all remaining statewide prohibition statues in 1938 when he signed the Revenue Tax Act to Legalize and Control Alcoholic Beverages and Liquors. On the first day the city of Atlanta considered liquor licenses in over twenty-two years, the city council approved sixty-four retail package stores and twelve wholesalers.

Even after the repeal of statewide prohibition, laws designed to enforce religious standards—better known as blue laws—placed some restrictions on alcohol in Georgia. In 2011 Georgia Governor Nathan Deal signed a bill allowing communities to vote for the first time on the question of Sunday alcohol sales at convenience and package stores. Georgia was the last southern state with a “blue law” banning Sunday sales.