Royal Georgia refers to the period between the termination of Trustee governance of Georgia and the colony’s declaration of independence at the beginning of the American Revolution (1775-83). During that period the province was administered in theory by the king of England but in practice by a member of his cabinet known at various times as secretary of state for the Southern Department and secretary for America. A provincial council provided a semblance of government during the years 1752-54 while the Georgia charter passed through parliamentary committees and received the royal signature. John Reynolds, the first royal governor of Georgia, proved ineffective and was recalled at the end of 1756. The second royal governor, Henry Ellis, established a sound foundation for government during his four-year administration. James Wright, who replaced Ellis in 1760, proved to be an efficient administrator and a popular governor. During his tenure in office Georgia enjoyed a period of remarkable growth.

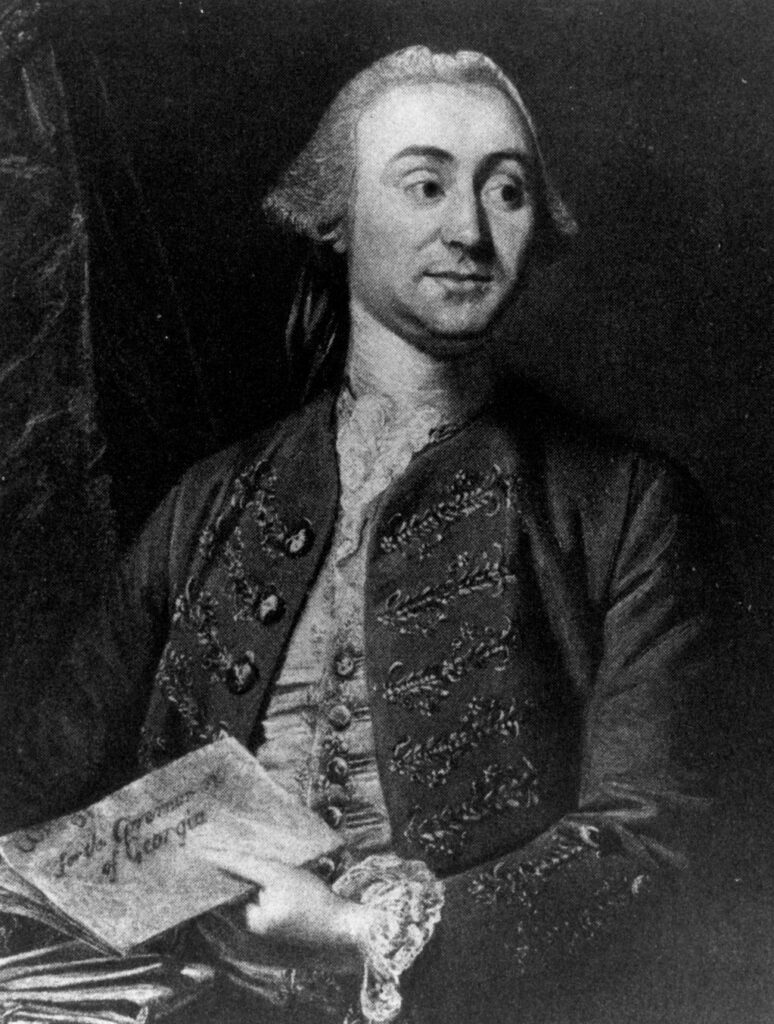

The Reynolds Administration, 1754-1757

In 1752 a committee of Parliament called the Board of Trade acquired the authority to nominate colonial officials. George Montagu-Dunk, Lord Halifax, the board’s president, intended Georgia’s charter to be a model for other American colonies. The charter provided for a strong governor empowered to convoke an assembly, pass on legislation, propose the erection of courts, approve land grants, enforce the laws, and otherwise administer the province. Other officials included an attorney general, a provost marshal, a clerk of council, a receiver of quitrents, a surveyor, and various customs officials. The legislature consisted of an assembly of two representatives from each county of the colony, which were created as soon as possible. In addition, there would be a council that would act as an upper house, as well as a court of appeals. The Board of Trade nominated the governor and members of the council, subject to the approval of the king.

Most Georgians welcomed Governor John Reynolds when he arrived from England on October 29, 1754. However, Reynolds, a career naval officer, lacked the political experience and skills necessary to the establishment of a model government. At the outset he alienated a backcountry faction headed by Edmund Gray, a Quaker planter and an influential Georgia politician, by refusing to inquire into claims of fraud in Georgia’s first election in 1754 and by branding the protestors as rebels. Then the governor frustrated the members of his council by awarding the most lucrative colonial offices to William Little, a naval surgeon who accompanied him to Georgia. When the council turned against him, the governor allied himself with his former enemies, the Gray faction, who shared his dislike of the Savannah-dominated council. Reynolds showed an equal lack of skill in Indian diplomacy, a crucial matter because his first year of office coincided with the beginning of the French and Indian War (1754-63). Georgia was dangerously exposed to raids by the Creek and Cherokee nations, and the Louisiana French hoped to instigate such attacks.

Lord Halifax reacted to the chorus of complaints from Georgia by recalling Reynolds at the end of 1756 and naming Henry Ellis as his successor.

The Ellis Administration, 1757-1760

Henry Ellis was a member of the Irish Protestant landed gentry. He might have been named the first royal governor of Georgia except that in 1754 he was out to sea as captain of his vessel, Earl of Halifax. Ellis possessed important qualities Reynolds lacked: intelligence, tact, sensitivity, wit, and political ability.

Ellis disembarked in Charleston, South Carolina, on January 26, 1757, and proceeded to Savannah, where crowds welcomed him as a deliverer from the unpopular Reynolds regime. Reynolds’s supporter William Little had been elected Speaker of the assembly and prepared a speech opposing Ellis. Anticipating opposition, Ellis simply adjourned the assembly until Reynolds and Little left Georgia under orders to report to Lord Halifax.

Ellis deserves to be remembered as the second founder of Georgia, after General James Oglethorpe. After no representative government under the Trustees and a bungled administration under Reynolds, Ellis taught Georgians the art of self-government. He explained the need for a budget and for raising taxes to support expenditures; he quieted factionalism; and he proposed necessary legislation establishing public credit, regulating Indian trade, clarifying land titles, and defending the province by forts, including one around Savannah. Mindful of his orders to establish counties, Ellis proposed the establishment in 1758 of eight electoral districts called parishes. The legislation wisely refrained from imposing the established church upon such dissenters as the Lutheran Salzburgers at Ebenezer.

Ellis tried to abolish slavery by proposing legislation to free mulattoes, thereby creating a class between white and Black members of society, and freeing all enslaved people when they reached the age of thirty. In that effort he failed. Instead, slavery, which had been legalized by the Trustees in 1751 after growing opposition to the colony’s ban, continued to have great effect on Georgia’s political and agricultural structure. Rich planters from the Carolinas flooded into Georgia’s lowland in the early 1750s, and within twenty years about sixty of these planters owned half of Georgia’s enslaved population and dominated Georgia’s rice economy. Between 1750 and 1755 the number of enslaved people in the colony grew from about 500 to 18,000, and in the mid-1760s Georgia began importing captive workers directly from Africa.

Poor health forced Ellis to leave Georgia in 1760. A grateful Halifax appointed him governor of Nova Scotia. Ellis never went to his new post, however, because, as an expert in American affairs, his advice was useful to the new secretary of state, Charles Wyndham, Lord Egremont. Ellis thus returned to England.

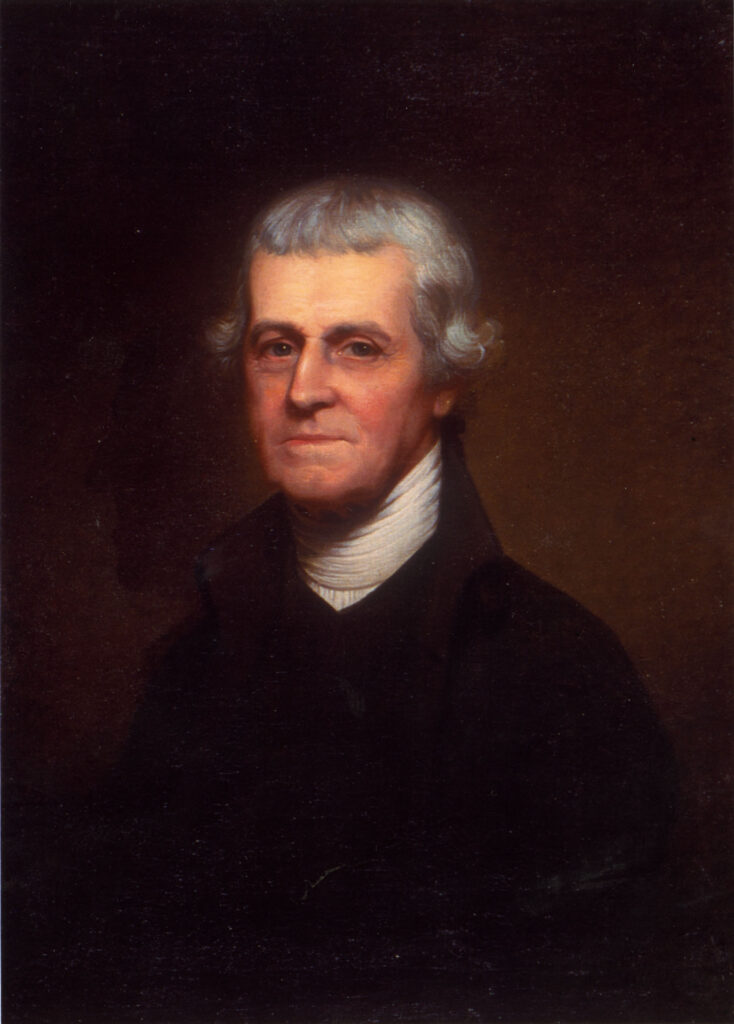

The Wright Administration, 1760-1776

James Wright understood colonial government, having served as South Carolina’s attorney general from 1742 to 1757. He benefited from several weeks of coaching by Henry Ellis before Ellis left Georgia in 1760, and he continued Ellis’s policies. He also had the advantage of more politically educated Georgians serving in the assembly. Governor and assembly agreed that Georgia needed more people and more land for settlement. During the French and Indian War (1754-63) available land for settlement was restricted to the tidewater region. The peace settlement of 1763 made Georgia a virtual empire, stretching to the St. Marys River in the South and the Mississippi River in the West; however, the Indian nations of the interior actually possessed the land, and the Creeks claimed all the territory west of the Savannah River above the tidal flow.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

In 1763 Governor Wright and British Superintendent for Indian Affairs John Stuart, abetted by influential traders Lachlan McGillivray and George Galphin, arranged a cession of the territory between the Savannah and the Ogeechee rivers as far north as the Little River. The Proclamation of 1763 forbade settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains and had the effect of funneling westward migration into the Georgia backcountry around Augusta. Those who had the land legally surveyed and recorded Wright called the “better sort,” but he admitted that most were squatters who disregarded all laws. Wright and his friends called those newcomers “crackers.” Inevitably, friction began between the settlers who coveted Indian land and the Indians who continued to travel the old trails to Augusta.

In order to grow the population of the 1763 cession, the assembly created two townships: Wrightsborough on the Little River and Queensborough on the Ogeechee River. A number of law-abiding Quakers from North Carolina lived together in Wrightsborough, but the Queensborough settlers scattered into individual farms. An opportunity for further expansion appealed to Governor Wright when, in 1771, Cherokee traders informed him that those Indians were willing to exchange land above the Little River if the government would assume the debts they owed to their traders. Wright thought so well of the idea that he went to London in 1772 to persuade the ministry that the increase in settlement would provide greater security against future Indian attacks. He returned in 1773 as Sir James Wright with royal approval of the proposed second cession. In May 1773 the reluctant Creeks (who were now also in debt) joined the Cherokees at Augusta and signed away land above the Little River. The Creeks refused to yield the territory west of the Ogeechee River that Wright had hoped to obtain. Wright toured the “Ceded Lands” and widely advertised their advantages, stressing the distance from New England and the tumult caused by the British tax on tea.

Georgia experienced its own kind of tumult when dissident Creek and Cherokee Indians raided the frontier settlements near Wrightsborough in the winter of 1773 and 1774. The outbreak prevented the hoped-for influx of settlers. Wright secured the cooperation of the other southern colonial governors in prohibiting trade with the Indians while the violence lasted. The boycott worked: in April Creek leaders asked for peace, and in October a treaty was drawn up in Savannah. Wright disappointed backcountry expansionists by neglecting to obtain a further cession of land as a condition of peace, and they accused the governor of favoring the Indian traders and merchants. The outlying parishes that had supported Wright now joined the Lowcountry radicals in opposing the British “Intolerable Acts.”

Opposition to parliamentary efforts to tax the colonies began in Georgia with the Stamp Act in 1765, quieted with the repeal of that act, then simmered while Indian negotiations preoccupied the province. From 1771 to 1773 Wright and the Commons House quarreled over the house claim to elect its Speaker over the governor’s veto. The house insisted on electing Noble W. Jones despite Wright’s disapproval, and the governor retaliated by dissolving that and successive sessions of the assembly until Jones ended the impasse by abstaining from election.

Courtesy of Telfair Museums.

On January 18, 1775, Georgians attended a Provincial Congress in Savannah to decide whether to join the Continental Association and ban trade with Britain. St. John Parish, a hotbed of revolutionary fervor, adopted the association and criticized the other parishes for their timidity. Only St. Andrew followed the lead of St. John. (The parishes were political as well as ecclesiastical divisions, corresponding to the original counties of 1777. Parishes elected delegates to the Commons House of the Assembly.) At the Provincial Congress, Georgians were too divided to take action, and the delegates elected to the Continental Congress declined to go to Philadelphia. Only Lyman Hall attended the Second Continental Congress in May 1775 as a representative of St. John Parish.

News of the first battles of the Revolutionary War (1775-83) at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts reached Georgia on May 10, 1775, and spurred the radical movement. On July 4, 1775, a second Provincial Congress met at Tondee’s Tavern in Savannah, agreed to join the Continental Association, elected delegates to Congress, and established a standing committee called the Council of Safety. By year’s end the Council of Safety had effectively preempted Governor Wright’s authority. Local committees made up of Sons of Liberty enforced the ban on trade, at times by the use of tar and feathers.

When British warships sailed into the Savannah River on January 18, 1776, to seize vessels loaded with rice, Wright left Georgia aboard the HMS Scarborough. Georgians adopted a rudimentary constitution called “Rules and Regulations” on May 1, 1776, and elected Archibald Bulloch president. On July 4, 1776, George Walton, Lyman Hall, and Button Gwinnett signed the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, bringing an end to the period of royal government. A war had to be fought before independence was assured. Wright returned in 1779 and continued as governor of the British-held portion of Georgia until 1782.