Georgia’s first railroad tracks were laid in the mid-1830s on routes leading from Athens, Augusta, Macon, and Savannah. Some twenty-five years later, the state not only could claim more rail miles than any other in the Deep South but also had linked its major towns and created a new rail center, Atlanta. The railroads continued to expand until the 1920s, when a long decline began that lasted into the 1990s. Today, the state’s rail system is a strong, 5,000-mile network anchored by two major lines, Norfolk Southern and CSX, and a couple dozen shortlines.

Early Years, 1830s to the Civil War

Charleston, South Carolina, provided the impetus for rail development in Georgia. In 1830 it began building a 136-mile railroad to Hamburg, on the Savannah River opposite Augusta. Savannah businessmen, worried that Charleston would benefit at their expense, responded by organizing the Central Rail Road and Canal Company. The state legislature, meeting in Milledgeville, issued a charter for the company in December 1833. The canal division of the company was soon dropped in favor of the construction of railroads, which were not as limited as canals with regard to where they could be built. Construction began in December 1835. The Central Rail Road of Georgia eventually became the Central of Georgia Railway, a 190-mile line across the Coastal Plain to Macon.

Meanwhile, construction on the Georgia Railroad between Augusta and Athens and on the Monroe Railroad (later the Macon and Western) between Macon and Forsyth, was in progress. The Georgia Railroad Company was chartered to a group of Athens businessmen in 1833 for the purpose of building a railroad from Augusta west into the interior of the state. In 1835 the charter was amended to allow banking operations, and the name was changed to Georgia Railroad and Banking Company. Company headquarters moved from Athens to Augusta in 1840. The Georgia Railroad was completed to Marthasville (later Atlanta) in 1845.

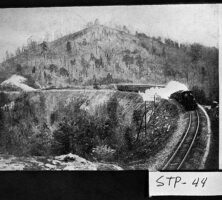

In the northwestern part of the state, an effort was underway to build a “state railroad” to the Tennessee River, a rail link that would open Georgia to the trade of the Tennessee and Ohio valleys. The state-owned Western and Atlantic Railroad (also known as the W&A), established by the state legislature in 1836 and completed in 1851, connected with Chattanooga, Tennessee, and accomplished that goal.

The W&A’s southern end was at Terminus (later Atlanta), where it joined the Georgia Railroad from Augusta and the Macon and Western from Macon. In 1854 a fourth rail line, the Atlanta and LaGrange Railroad (later the Atlanta and West Point Railroad), entered Atlanta from the southwest, and soon the city became a rail hub for the entire South. When the Civil War (1861-65) broke out, Atlanta became a key military target due to its importance in shipping supplies to the Confederate troops. Union general William T. Sherman’s troops finally seized the city in 1864 after a series of hard-fought battles in the Atlanta campaign along the route of the W&A.

Postwar Expansion and Consolidation

After the war, investors began building new lines and acquiring existing railroads, consolidating them into larger systems. A Connecticut entrepreneur, Henry Bradley Plant, purchased several railroads in the South in the 1880s and 1890s. Although his railroads generally kept their original names, Plant operated them in a unified manner, as a system. In south Georgia the Plant System reached across the state from Savannah to Alabama and Florida. In north Georgia, the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia (also known as the ETV&G) expanded from Dalton west into Alabama and south to Atlanta, Macon, and Brunswick. Also in north Georgia, the Virginia-based Richmond and Danville system stretched across the southern Piedmont, connecting Richmond, Virginia; Atlanta; and the Mississippi River.

During this period the Central of Georgia expanded and assisted other railroad-building efforts in Georgia through loans and stock purchases. It also acquired a number of existing railroads and created subsidiaries to expand its own lines. By 1929 the Central had created a nearly 2,000-mile network, reaching across much of Georgia into Alabama and Tennessee. At various times it was controlled by several different larger railroads, among them the Southern, which bought the Central in the 1960s.

A holding company, the Richmond and West Point Terminal and Warehouse Company, controlled the Richmond and Danville beginning in 1880 and the ETV&G beginning in 1887. When the holding company collapsed in 1892, the banker J. P. Morgan created Southern Railway out of the financial wreckage. Southern would become one of the dominant railroad systems of twentieth-century Georgia.

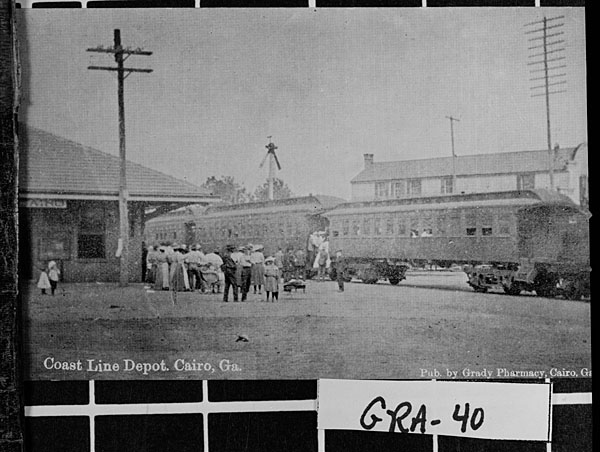

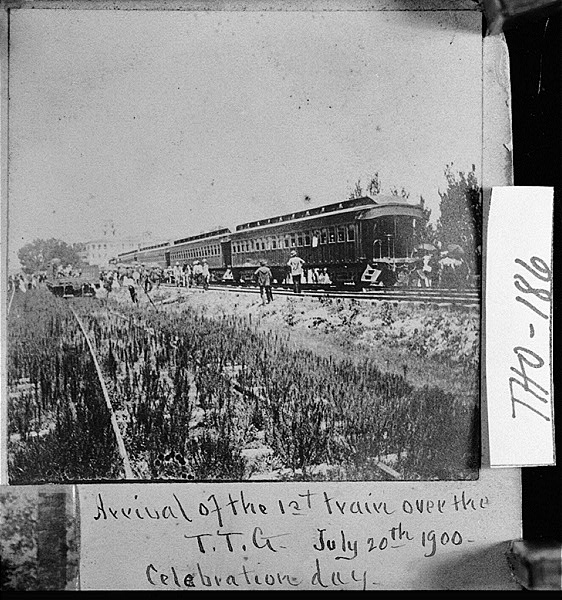

In 1900 two other major systems, the Atlantic Coast Line (ACL) and the Seaboard Air Line Railway, were established. ACL gained dominance in south Georgia through its purchase of the Plant System in 1902. Seaboard’s predecessors had acquired major lines in the Georgia Piedmont and Coastal Plain; these were supplemented in 1904 by a link from Atlanta to Birmingham, Alabama.

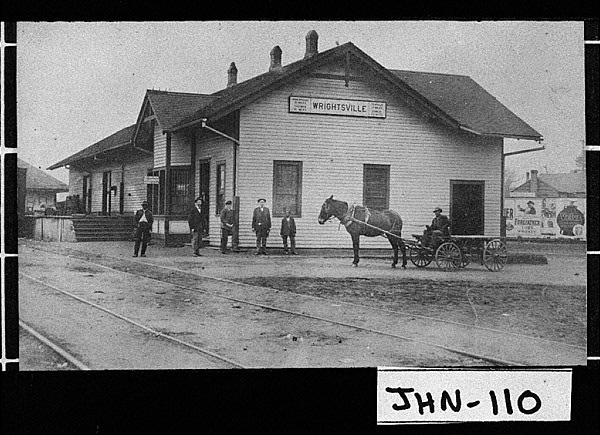

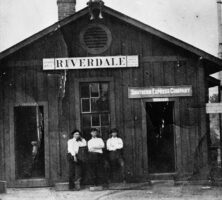

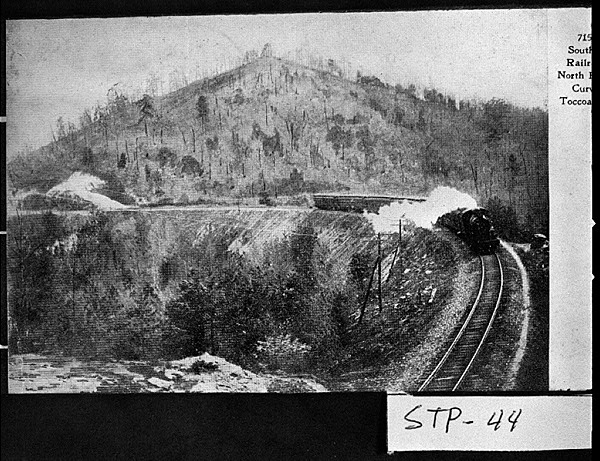

Connecting to the major systems were such shortlines as the Wrightsville and Tennille and the Tallulah Falls. Many of these were controlled by larger railroads, typically through stock ownership. At the bottom of the railroad hierarchy were the logging lines, scattered across the state from the Appalachian Mountains to the Okefenokee Swamp. Most were abandoned after the forests were cut, but a few became “common carrier” lines, carrying freight of many types, at least for a time.

Decline and Renewal, 1920s to the Present

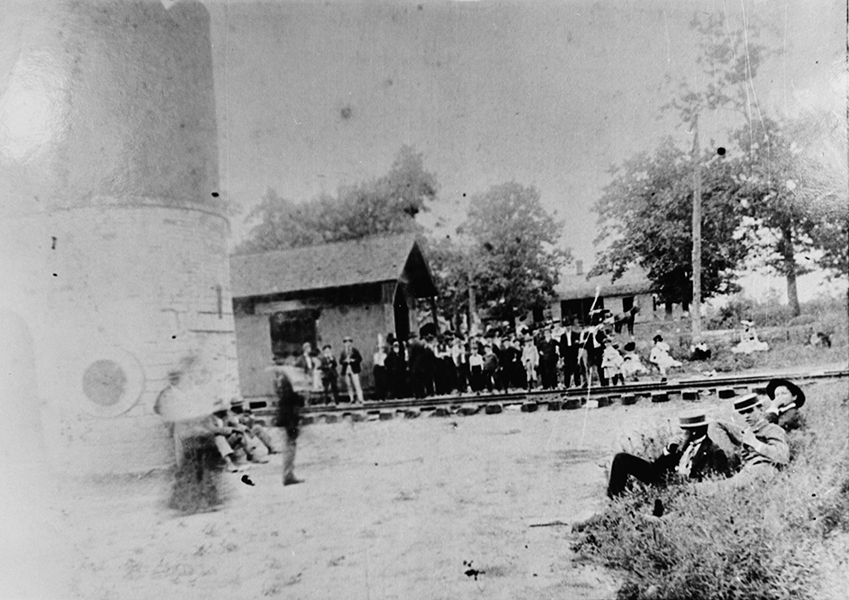

By the 1920s railroads covered almost all of Georgia, and the period would prove to be the high point of railroad service in the state, although some residents of mountain counties had never seen a train other than the log-haulers.

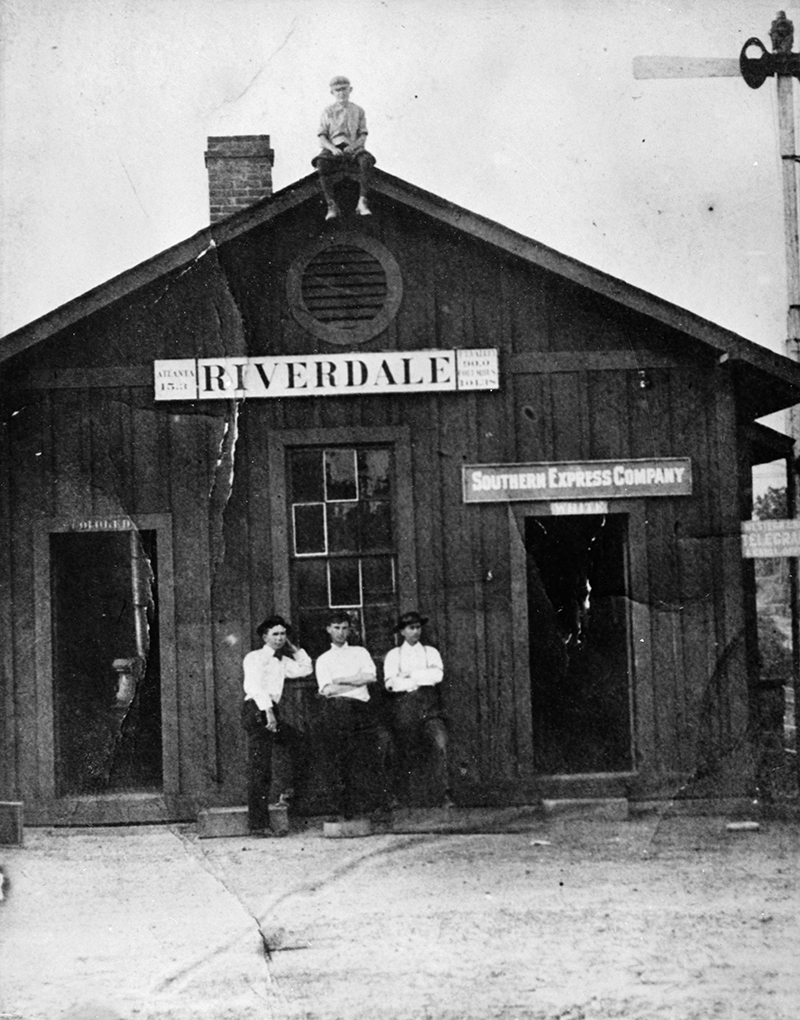

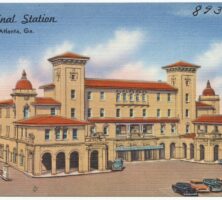

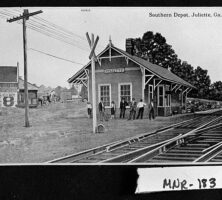

Passenger service declined steadily after 1920, except for a brief resurgence during World War II (1941-45). Automobiles were becoming affordable for the average family, and an ever-rising number of new drivers called for improved roads. As the roads improved, rail passenger numbers declined. The low point came in the 1960s and 1970s, as the great terminal stations and union stations in Atlanta, Augusta, and Savannah were demolished. Hundreds of small-town depots were likewise torn down, moved, or converted to other uses.

A declining passenger business, however, was a small part of the railroads’ decline; they continued to lose the much-larger freight business to trucks, and they could not attract the capital investment to maintain thousands of miles of lightly used track. The Staggers Rail Act of 1980 extensively deregulated the railroads and put them on a stronger financial footing, but it led to the abandonment of hundreds of railroad miles, including tracks that had once served as main lines. Some of these have since been purchased by the Georgia Department of Transportation and leased to shortline companies, but others have been lost forever.

Today, most railroads are financially sound, but there are many fewer than before. In Georgia, most freight traffic is carried by only two: CSX (successor to ACL and Seaboard) and Norfolk Southern (successor to Southern Railway and Central of Georgia). Twenty-three shortlines serve as local feeders to the main lines. Passenger service, which never disappeared entirely, is available on two Amtrak routes. One route, known as the Crescent, runs from New York to Washington, D.C., through north Georgia and Atlanta and on to New Orleans, Louisiana. The other runs from New York to the Georgia coast and on to Florida.

Railroads and the Creation of Towns

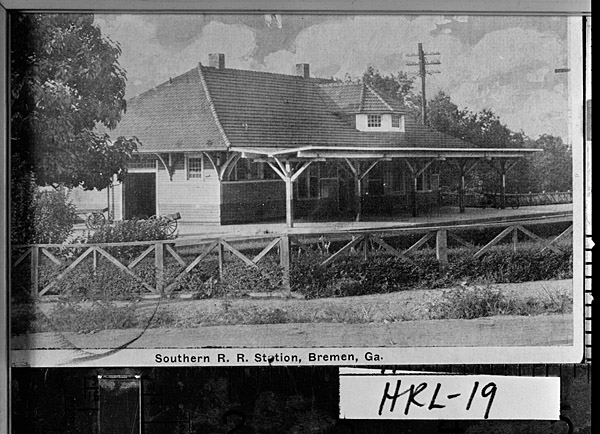

A great many Georgia cities and towns, including Alamo, Baxley, Bremen, College Park, Cornelia, Manchester, Millen, Pembroke, Smyrna, Soperton, Waycross, and Winterville, owe their existence to the railroads. The growth in the number of towns engendered by the railroads was due in part to the steam trains’ need to stop frequently for water (to be converted into steam) and fuel (first wood, later coal). Also, some railroads were built not to connect existing towns but to connect distant points, such as the coast with the Tennessee River, Atlanta with the Mississippi River, or Savannah with the Gulf Coast. Their routes were often laid out with an eye toward economy of construction or a direct route versus a concern over connecting existing towns. Often there were very few towns to connect anyway, such as in south Georgia, when the Atlantic and Gulf Railroad was built from Savannah to Bainbridge.

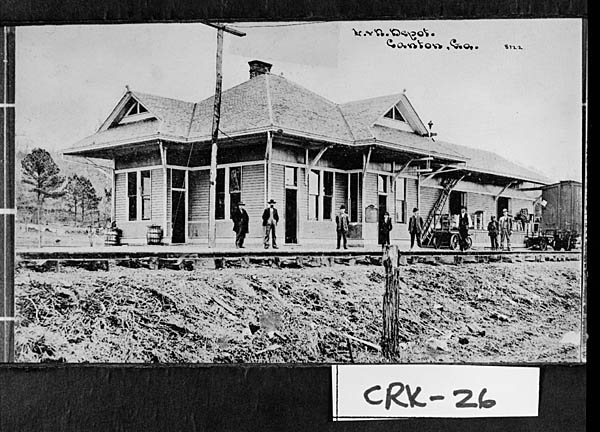

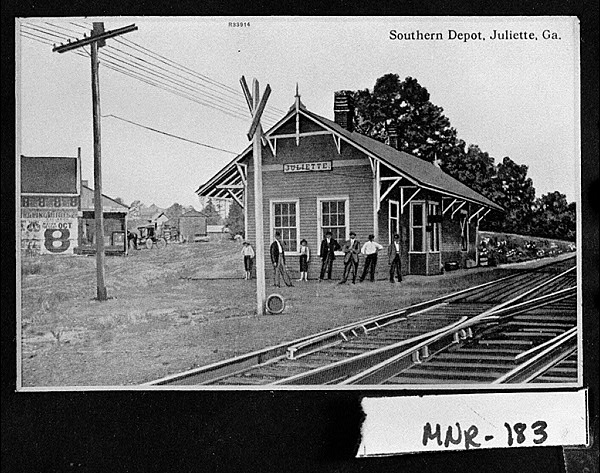

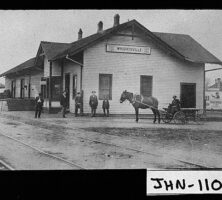

Once the railroads came through an area, towns grew up along them, frequently at points where trains would stop for water and fuel. A depot would be built and businesses would locate nearby to take advantage of the concentration of potential customers. Other businesses would be established to provide such services as lodging, saloons, livery stables, blacksmiths, warehouses, and milling. Eventually a town or city would develop.

Often a city would be incorporated with its boundaries legally defined as a circle with the railroad depot in the center. For instance, the boundaries of Dalton were defined as one mile in every direction from the depot.

In several cases county seats were moved to be on the railroad. In Lowndes County the seat was moved from Troupville to Valdosta, a new town on the Atlantic and Gulf. In Fannin County the seat was moved from Morganton to Blue Ridge, a new town on the Marietta and North Georgia Railroad. In Bartow County the seat moved from Cassville to Cartersville, and in Jones County the seat moved from Clinton to Gray. In other cases the county seat remained off the railroad while a larger town developed on the rail line, as was the case in Crawford County, where the new railroad town of Roberta grew to surpass the seat, Knoxville, in size.

Today, railroads are a major part of Georgia’s freight infrastructure. The port of Savannah—the fourth busiest container port in the country in 2015—and the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport both depend on Georgia’s interstates and railroads to ship goods into the interior of the country. By 2014 CSX, one of the two largest rail operators in the state, had handled more than 1.9 million carloads of freight in Georgia and was operating nearly 27,000 miles of track.