The wiregrass region of Georgia, located today in the state’s southernmost section, once stretched from Savannah to the Chattahoochee River and covered all or portions of twenty-three counties, according to the 1880 U.S. census report on cotton production. The boundaries of the region have shifted over time in response to deforestation and commercial agriculture.

Ecology and Geology

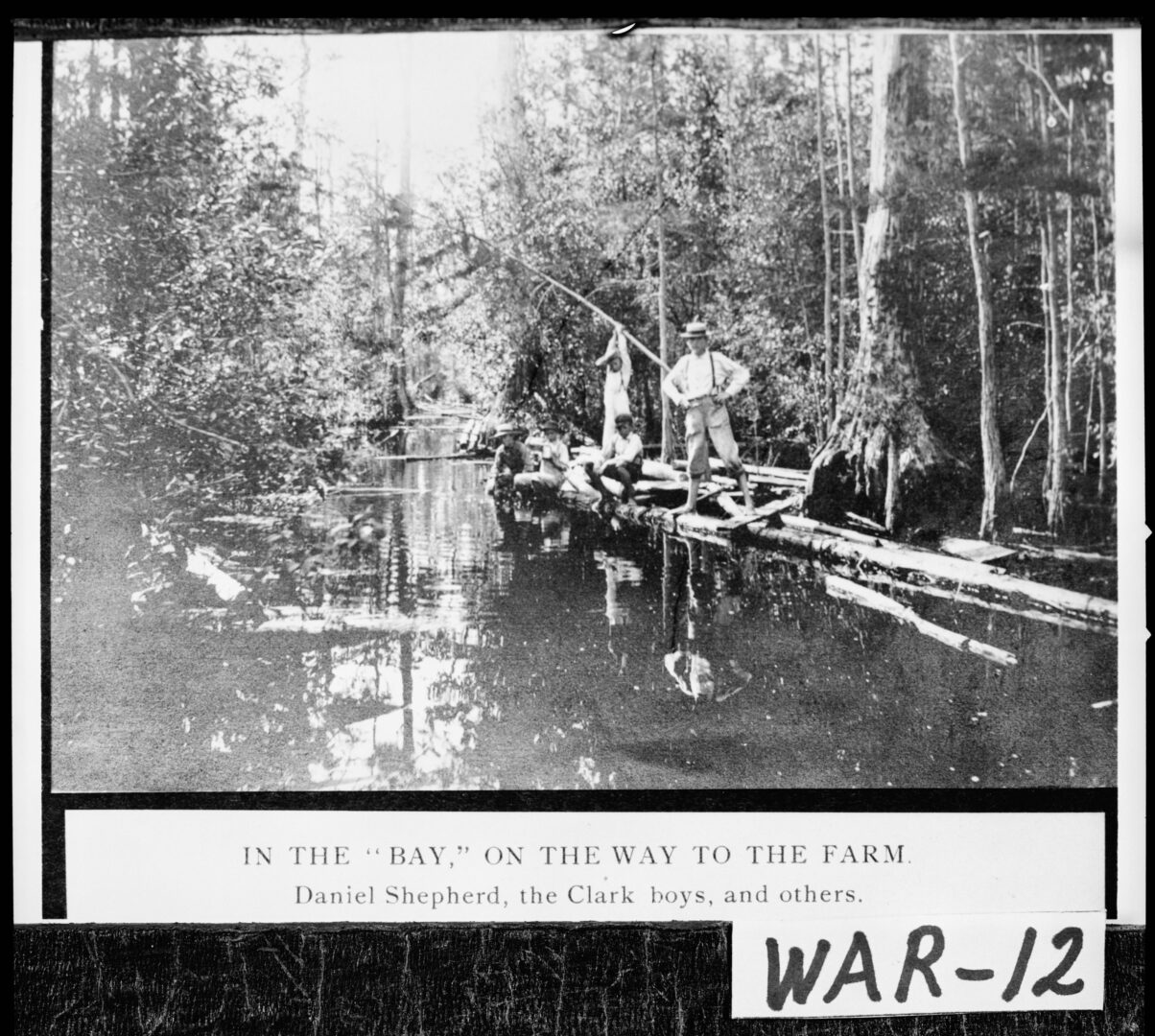

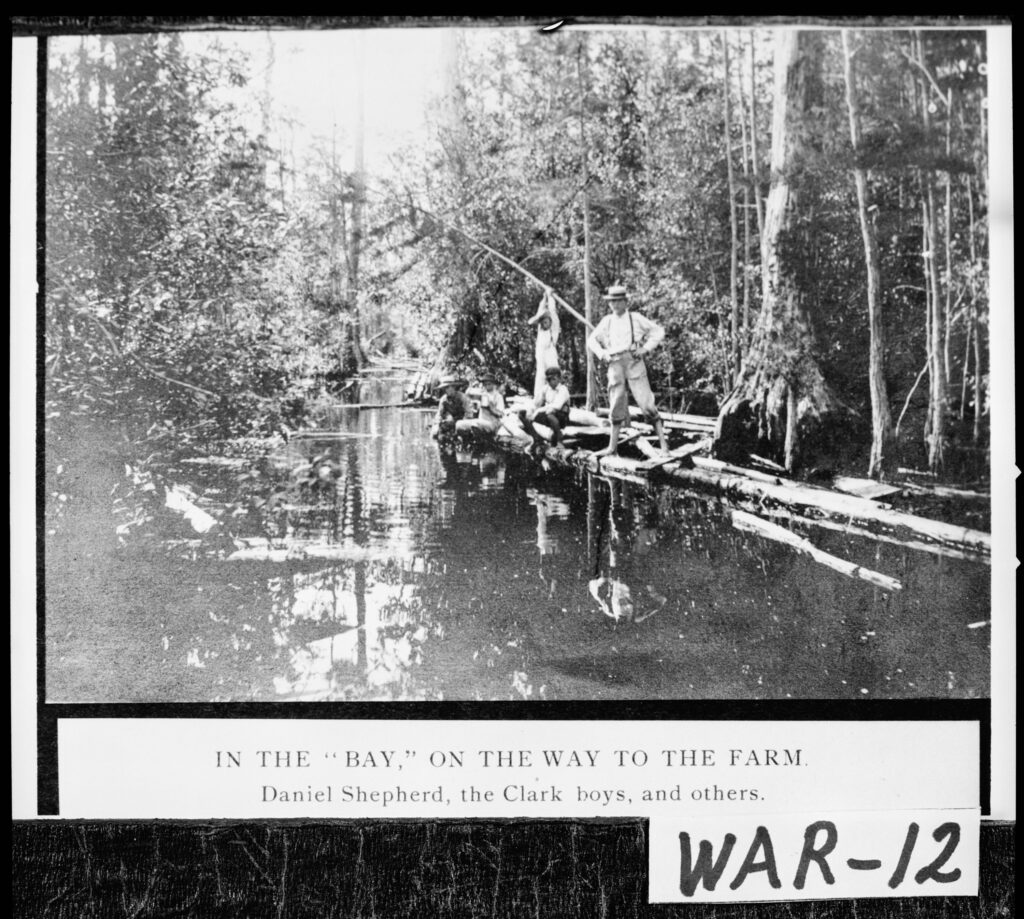

The major features of Georgia’s wiregrass region are the pine trees and wiregrass growing on its sandy soils, as well as the many creeks, rivers, and swamps that form its wetlands. A round-bladed perennial growing in outwardly bending clumps, wiregrass (Aristida stricta) reaches a height of more than one foot and lends the region its name. With the exception of low and swampy areas, wiregrass once carpeted the forest floor of the state’s Upper and Lower Coastal Plain, forming an extensive open range for wild game and livestock. The Atlantic Ocean and Gulf Coast water divide runs in a northwesterly to southeasterly direction, roughly through the center of the region, and separates the watersheds of rivers that flow into the Atlantic, like the Altamaha, Ogeechee, and Satilla, from those that empty into the Gulf of Mexico, like the Alapaha, Flint, and Withlacoochee. Another notable feature of wiregrass Georgia is its karst landscape, or lime-sink section. Located in the western portion of the region, the lime-sink section comprises sinkholes, caves, springs, and disappearing streams.

The wiregrass region of Georgia is the state’s youngest in geologic time. One million years ago the area was underwater, forming part of a sea whose shoreline corresponded with the present fall line. As the ocean receded, a series of five sandy terraces emerged above sea level. The highest of these, the Hazlehurst Terrace, reaches an altitude of about 215 to 260 feet. The seemingly endless expanse of pine forest was later divided into three main divisions: the pine and palmetto flats in the east, the gently rolling “pine barrens” of the interior, and the western lime-sink region.

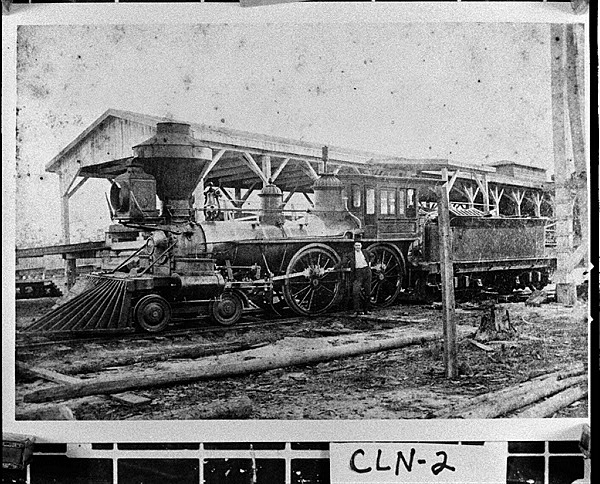

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Early travelers frequently noted the woodland’s open and parklike appearance, the result of a pine canopy that shaded out most undergrowth on the sandy uplands. This canopy was created by the region’s most conspicuous form of plant life, the longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), which like wiregrass lends its name to the area as “pine barrens” and “piney woods.” Plant life in the bottomlands was more diverse, including mixed stands of oak, gum, hickory, sycamore, magnolia, and cypress, as well as smaller plants like cane and saw palmetto. The naturalist William Bartram and his father, John, discovered a rare species of gordonia (Franklinia alatamaha), also known as the Franklin tree, along the lower Altamaha in the 1760s. The forest also supported a rich and diverse fauna, including bears, deer, gophers, rattlesnakes, and wolves, as well as wild hogs called “piney-woods rooters.”

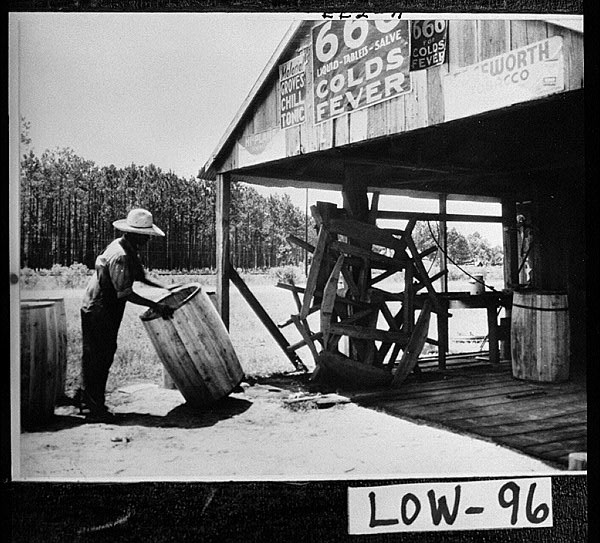

Image from John Donges

Economic change and immigration in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had a profound influence on the region’s environmental history. Deforestation altered a unique ecological system, gradually removing much of the virgin forest and its canopy, and transforming it into a landscape of cotton farms and trading towns. Timber clearing and land cultivation increased agricultural runoff, the silting in of creeks and streams, and the evaporation of water in the region’s shallow creeks. Today, mixed farming, including the cultivation of peanuts, soybeans, Vidalia onions, and trees, continues to give the area an overwhelmingly rural appearance.

Human History

For much of Georgia’s history, the wiregrass region has been viewed as one of the state’s poorest areas, an isolated and impoverished land of hookworm, pellagra, and poor whites. But its human history is much more complex. Its native inhabitants included the Hitchiti, who were evidently living along the Ocmulgee River when the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto passed through wiregrass Georgia in 1540, on his way from present-day Florida into the Carolinas. By the time of sustained European contact and settlement, the Lower Creeks hunted and occupied parts of the region.

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the forest was settled as part of a larger folk migration of Euro-Americans and enslaved African Americans from the Carolinas and, to a lesser degree, Virginia. These settlers were primarily involved in self-sufficient farming and livestock herding, and in Georgia’s Coastal Plain they found a familiar environment—including cheap land, open range, and relatively few planters and enslaved laborers. This process of occupation and settlement began in the eastern part of the wiregrass region during the late colonial period and continued westward with each new Indian land cession until the 1820s, when the final cession was made by the Lower Creeks. Throughout the antebellum period, small farmers continued to clear patches of new ground for agricultural purposes.

Photograph by Chris M. Morris

Because of its early reputation as a barren region of limited agricultural possibilities, however, the wiregrass forest remained out of the mainstream of colonial and antebellum commercial agricultural expansion. In many respects the area formed borders for Georgia’s richer cotton- and rice-producing regions. Because they both occupied interior woodlands, often associated in the European mind with “wild” places inhabited by Indians, and made few changes to the natural landscape, wiregrass Georgia’s white settlers in time were branded by their wealthier neighbors as lazy, poor, primitive, and violent. These characteristics, previously ascribed to Indians, form the basic features of the “

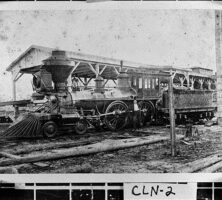

On the eve of the Civil War (1861-65), wiregrass Georgia was among the most sparsely populated sections of Georgia and the eastern United States. A “white man’s country” with few enslavers and fewer planters, most white farming families worked fewer than 100 acres of land, producing food crops primarily for home consumption. Small quantities of cane syrup, cotton, hides, and wool were annually hauled to market towns like Savannah and traded for store goods. Because of its overwhelmingly rural and self-sufficient nature, the region had few towns of any size, with the largest ones situated on the edges of the pine forest. Only one railroad, a line running from Thomasville to Savannah, crossed wiregrass Georgia in 1861.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Because it was a relatively poor region characterized by low slaveholding, secessionists feared that the region’s farmers would not support disunion or rise to the defense of a slave society. But wiregrass Georgia, like the state as a whole, was badly divided during the secession crisis.

During the Civil War, infantry companies with names like the Irwin County Cowboys and the Forest Rangers (from Clinch and Ware counties), reflecting the region’s almost frontier-stage culture, were shipped off to the front. Anti-Confederate sentiment raised its head among the region’s Unionists as the war wore on, and pockets of deserters, aided by family and friends, found refuge in the woods.

Manpower losses and impoverishment left many postwar communities in a vulnerable condition. Some families sought to regain economic self-sufficiency by returning to such traditional economic pursuits as farming, timber cutting, and livestock herding. Two major developments, however, made such pursuits increasingly difficult. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the rise of both national and international markets for longleaf pine, as well as extensive railroad construction, opened the forest to rural industrialization, largely in the form of the naval stores and lumber industries. Wherever railroads went, turpentine distilleries, sawmills, and market towns arose, transforming much of the landscape.

Much of the land in wiregrass Georgia originally was distributed by the state in lots as large as 490 acres. As long as grazing, self-sufficient farming, and scale timber cutting and rafting were the primary economic pursuits of the yeomanry, land holdings remained large. But as both northern- and southern-owned companies cut over the forest, the size of land holdings declined as the forest industries waned and agriculture became more important. Railroads offered cutover land for sale at rates ranging from $0.25 to $5.00 per acre, depending upon its distance from the railway.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

The lure of new agricultural land attracted diverse groups of newcomers to the wiregrass region, each with its own immigrant narrative. African Americans came to work in turpentine stills and sawmills; cotton farmers sought new ground for raising their crop; up-country Georgia farmers moved to the piney woods to escape fence laws; and small-town merchants and professionals sought new beginnings in railroad towns.

With each passing decade the percentage of wiregrass farms operated by owners declined, while the number of farms worked by tenants and sharecroppers increased. As cutover land was brought into cotton production through the use of commercial fertilizers, the region’s people became mired in the same crop lien system that plagued the rest of the South. Many rural farming families saw their status change from self-sufficiency to tenancy, working land on shares or renting it from others and struggling to finish the year out of debt to landlords and merchants. The arrival of the boll weevil during the late 1910s caused additional difficulties for cotton farmers, but the dependence upon cotton as a cash crop continued until the mid-twentieth century. Significant out-migration of the population after World War II (1941-45) virtually depopulated many rural communities.

Folklore and Literature

From William Bartram’s Travels to the present, writers have recorded vivid images of wiregrass Georgia. The country and its rural people inspired the folktales of John L. Herring, whose Saturday Night Sketches: Stories of Old Wiregrass Georgia (1918) describes events in the daily lives of wiregrass Georgia’s plain folk. Caroline Miller’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, Lamb in His Bosom (1933), was written while she lived in Baxley, and the novels and short stories of Bacon County native Harry Crews, particularly A Childhood: The Biography of a Place (1978), draw upon his memories of the lives and times of south Georgians in the twentieth century. Writer Janisse Ray has published two books about her experiences in the wiregrass region: Ecology of a Cracker Childhood (1999) is both a coming-of-age story and a call to preserve the rapidly disappearing wiregrass environment, and Wild Card Quilt: Taking a Chance on Home (2003) chronicles Ray’s return to her family’s homeplace in Appling County.