Progressive architecture in Georgia between the late 1920s and the late 1950s developed in sequential and overlapping phases of modern design that historians have identified as art deco, modern classic, streamlined moderne, and Bauhaus modern or International style.

Art Deco

Art deco is the most ornamental and cosmetic of these design movements, involving the application of either monochromatic or polychromatic decorative patterns to building facades and a sharp-edged faceted profile to natural, zoomorphic, or human forms applied in relief to those building surfaces. On P. Thornton Marye’s Southern Bell Building (1929, later the AT&T Building) by Marye, Alger, and Vinour in Atlanta, for example, this linear, apparently machine-cut work in sculptural relief is evidenced in monochromatic foliate panels, angular eagles, and sharp-edged human figures emerging from the walls as geometrically carved stone profiles. Atlanta City Hall (1930) takes on a neo-Gothic character; deco shared Gothic’s interest in organic, natural elements, but art deco more typically stylized and modernized traditional historic elements that were more explicitly classical in derivation. Pringle and Smith’s William-Oliver Building (1930), for instance, displays an ornamental stylist’s employment of abstracted Ionic volutes, a continuous cornice frieze accented with a string of zigzag chevrons, and flowing incised wave motifs treated as flat moldings and incisions in the monochromatic surfaces of the multistoried structures.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

The 1920s ornamental stylists who pioneered this new direction of a popularized and more decorative modernism were frequently trained in the Beaux-Arts tradition, itself grounded in the beliefs that beauty was derived from classical order and that ornament was based on nature. During the 1930s, the Beaux-Arts tradition of classicism survived in the more bureaucratic architecture of federal, state, county, and local governments, whose buildings displayed a more restrained aesthetic sometimes called Depression modern.

Modern Classic

The governmental modern classic was best seen in New Deal –era post offices, government office buildings, and especially county courthouses and jails, such as Burge and Stevens’s Atlanta Police Station and Jail (1934-35, razed). In Atlanta, A. Ten Eyck Brown’s Federal Post Office Building (1931-33, later the Martin Luther King Jr. Federal Building) was the largest construction project of its day in the state. It would be followed by Tucker and Howell’s monumental Georgia State Prison (1934-36) in Reidsville. Both works seemed keen to demonstrate the stability, power, and sheer weight of the government during a period when the national economy was at its most depressed and recovery was barely getting under way.

On the national front, architect Paul Cret was the leading designer in the modern classic, and his Folger’s Shakespeare Libraryin Washington, D.C. (1928-32), served as the model for the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Heisman Gymnasium and Auditorium (1934-39, razed), a Public Works Administration/Works Progress Administration project of Robert and Company and Bush-Brown and Gailey, with Matt L. Jorgensen.

A more widespread adoption of the style was found in county courthouses throughout Georgia. This emergence from deco was evidenced in 1937 at the courthouse of Mitchell County in Camilla, followed by no fewer than four modern classic county courthouses appearing in 1939: those of Cook County in Adel, Oconee County in Watkinsville, Quitman County in Georgetown, and Troup County in LaGrange; architect William J. J. Chase clad the latter in marble. Later examples include the courthouses of Emanuel County (1940, razed) in Swainsboro; Pickens County (1949) in Jasper; and Ware County (1957, very late for the style), clad in Georgia marble, in Waycross.

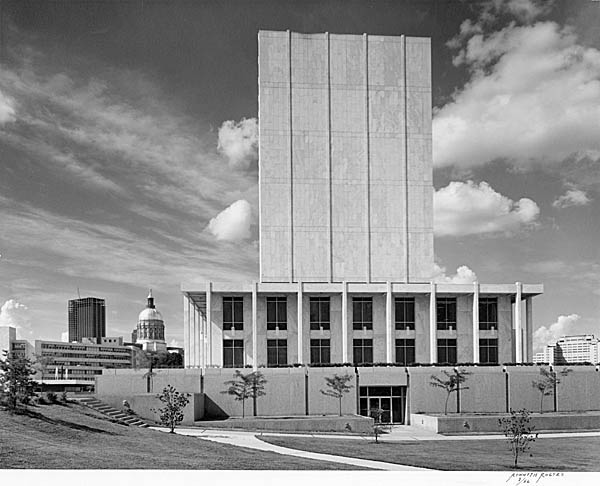

Occasionally accented by art-deco ornament, modern classic buildings at smaller scale remained monumental, yet restrained and simple. In less energetic forms (which appear weak compared with the Federal Post Office Annex in Atlanta or the Reidsville prison), A. Thomas Bradbury built a half-dozen white marble state office buildings during the 1950s and early 1960s, sited on blocks surrounding the state capitol in Atlanta. There, the enriched Beaux-Arts character of Edbrooke and Burnham’s capitol building (1884-89) is contrasted with the modernized classicism of Bradbury’s bureaucratic boxes for labor, health, agriculture, and trade. In the most handsome and minimalist of his designs in this mode, Bradbury ceremonially placed the Georgia Archives building on a classical base and thus created the state’s most monumental and pristine box, a surprisingly successful urban stela, or commemorative slab or pillar, that symbolically expresses, perhaps, that a stripped-down sarcophagus should be the ultimate repository of the state’s past life and culture.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Streamlined Moderne

The 1930s was a period dominated by the influence of industrial designers whose machines and product designs evidenced the period’s preference for streamlining. Modeled on the design of ships, planes, trains, and automobiles, streamlined moderne architecture offered a translation, in inert materials and stationary structures, of kinesthetic lines and streamlined forms. Dynamic moderne buildings were sometimes of ordinary and often transportation-related function, including gas stations, car dealerships, tire outlets, and drive-in restaurants, such as Atlanta’s renowned Varsity (1940) by Jules Grey. The off-street parking for George Harwell Bond’s Briarcliff Plaza shopping center (1939-40) in Atlanta reflected the designer’s intention to accommodate the automobile in the site plan.

Courtesy of Robert M. Craig

Greyhound Bus depots became icons of the streamlined moderne style. Savannah’s depot survives and is soon to be restored, but Atlanta’s depot (1940) by W. S. Arrasmith was brutally defaced by a facade modernization that made this one-time “classic” of the streamlined style impossible to detect. The depot was razed in 2005. A noteworthy and large-scaled moderne survivor, although slated for demolition, is Robert and Company’s Atlanta Constitution Building (1945-48), whose limestone panel depicting the newspaper’s role in Atlanta history, carved by Julian Hoke Harris, survives at the MARTA Omni Station.

Bauhaus Modern

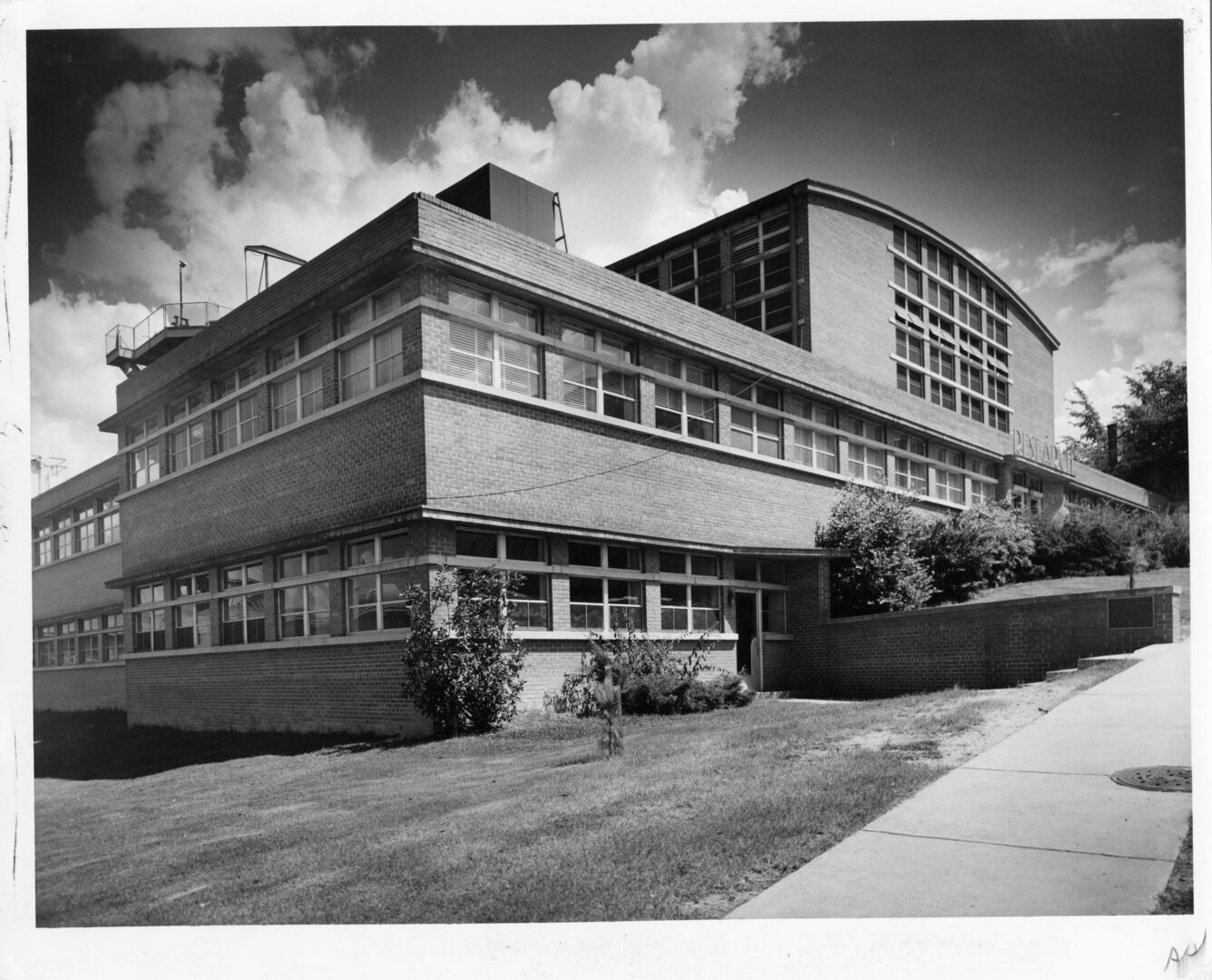

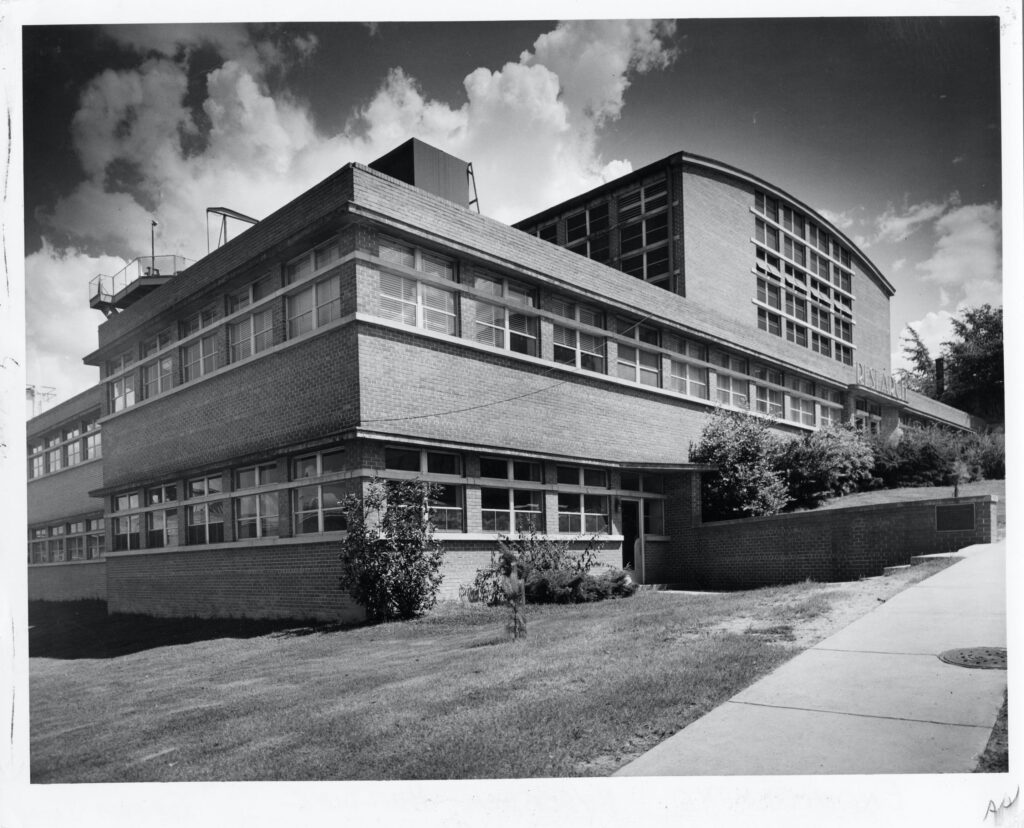

Increasingly abstract, the most progressive style of the late 1930s and 1940s was derived from the German art school the Bauhaus. Also identified as the International style, the volumetric, “white” aesthetic of steel, concrete, and glass was devoid of ornament and abstracted to an almost diagrammatic expression of function. Evidenced particularly in school designs, this modern style is seen in Paul Heffernan’s so-called academic village at the Georgia Institute of Technology, comprising the Hinman Research Building (1939), the Hightower Textile Engineering Building (1948-49, razed), the Architecture Building (1950-52), and the campus library (1951-53).

Courtesy of Georgia Institute of Technology Library and Information Center.

The modern aesthetic in Atlanta moved beyond Georgia Tech to Sparks Hall (1952-55) by Cooper, Bond, and Cooper at Georgia State University, to the private Lovett School (1959) by Richard Aeck, and to the public Price High School (1953-54, 1958 addition, razed) by Tucker and Howell. After their noteworthy E. Rivers Elementary School (1949), Stevens and Wilkinson led the progressive development of school design, spreading modernism statewide in elementary and high school designs in especially large numbers. The International/modern style was well established in school architecture when it was employed as late as 1968 in the Griffin-Hightower Science Center at Morris Brown College.

The modern aesthetic was especially intended to respond to housing needs and found expression internationally in public housing as well as in apartment towers. In Savannah, Drayton Towers is the city’s best modern glass tower, which, in the context of the city’s squares and against the texture of Spanish moss, also makes Drayton Towers “the building Savannahians love to hate.” In Atlanta, the Darlington Apartments skirts the edge of traditional and low-scale Brookwood Hills in comparable contradiction.

Modern and moderne detailing enriches housing units picturesquely sited in landscapes marked by set-back blocks, angular wings, courtyards, and corner windows, as illustrated at Peachtree Hills Apartments (1938, 1946, 1950, but soon to be razed) by Burge and Stevens, at Georgia Tech’s Callaway Graduate Student Housing (1947, razed) by Stevens and Wilkinson, and at the Briar Hills Apartments (1946-47) and adjacent Briarcliff Normandy Apartments (1949). Although Atlanta seems determined to wipe out this generation of architecture, some notable early modern office buildings survive; among the most notable is Cecil Alexander and Bernard Rothschild’s Peachtree-Seventh Building (circa 1949-50, later Atlanta Federal Building and then Peachtree Lofts). The two principals would soon join fellow architects Bill Finch, Miller Barnes, and Caraker Paschal to form FABRAP, a firm established in 1958.

Image from James Lin

An experimental effort to promote prefabricated, all-steel houses was introduced to the South when Lustron built a demonstration “Lustron House” (1949) on Northside Drive in Atlanta, which William R. Knight bought and lived in after he became a franchiser. A Westchester Deluxe two-bedroom Lustron, the Knight house encouraged others to contract for perhaps as many as ten Lustrons in Atlanta and Decatur in the early 1950s. Others are known to have been built in Albany, Americus, and Macon.

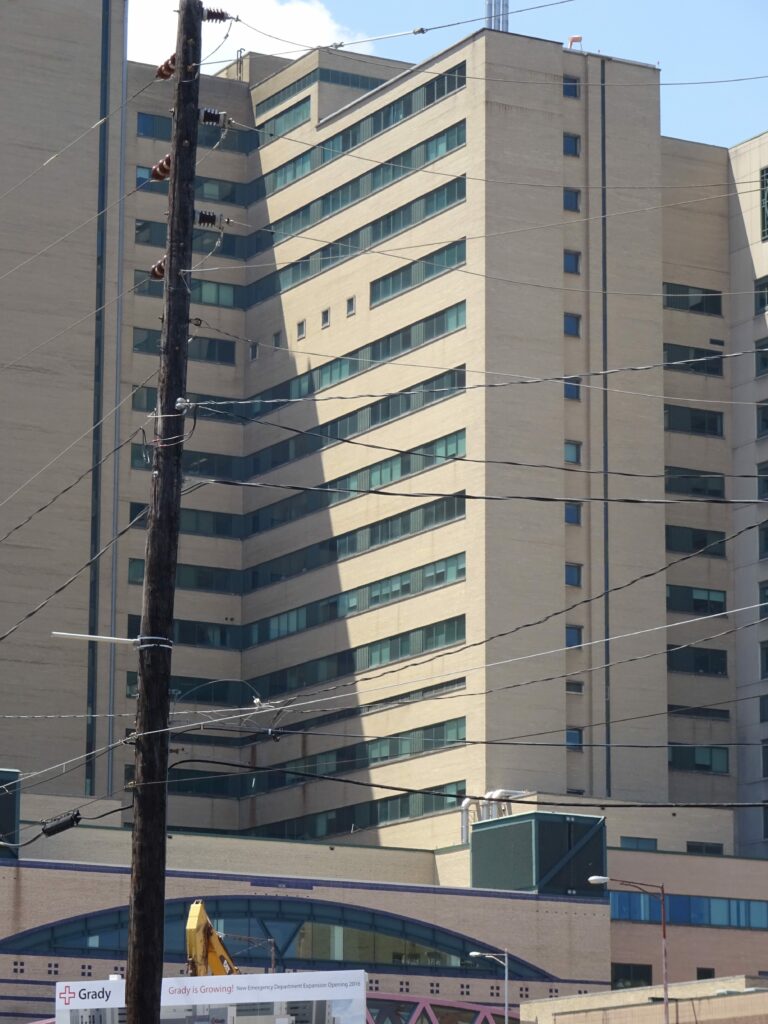

Both Robert and Company’s Grady Memorial Hospital (1954-58) and Stevens and Wilkinson’s Georgia Baptist Hospital, the 300 Boulevard Building (1948-51), represent early applications of the modern steel-frame aesthetic to hospital design. In Atlanta noteworthy modern church designs of the period before 1960 include Norman F. Stambaugh’s Druid Hills Church of Christ (1949-50); Philadelphia architect Harold E. Wagoner’s Lutheran Church of the Redeemer (1950-52), with its Deco overtones; Carol M. Smith’s Mount Zion Second Baptist Church (1955-56); and William F. Penney’s Immaculate Heart of Mary Church (1958), the latter enriched by sculpture by Julian Hoke Harris.

Courtesy of Robert M. Craig

The examples of Georgia’s modern architecture cited above suggest a time delay separating the birth of modern architecture in Europe in the 1920s, its appearance in the United States in the late 1930s, and its widespread adoption in Georgia after World War II (1941-45). By the late 1930s, former Bauhaus directors Walter Gropius and Mies Van der Rohe had left Europe for Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Armour Institute (later Illinois Institute of Technology) in Chicago, Illinois, respectively, and by the late 1940s their influence was being felt throughout the United States.

Mies called for a modernism reflective of modern technology and new materials, and his efforts to reduce and refine an aesthetic of steel and glass resulted in a minimalist Miesian aesthetic during the 1950s that detractors called “the corporate glass box”; admirers, however, considered Mies’s buildings to be elegant and the epitome of simplicity and refinement in the modern age. I. M. Pei’s Gulf Oil Building (1949) and Skidmore Owings and Merrill’s Equitable Building (1968), both in Atlanta, reflect early and late examples of this steel-and-glass aesthetic. A comparable Miesian quote is evidenced in Augusta in the First Union Building (1968) by Robert McCreary, exemplary of the curtain-wall aesthetic in black steel introduced by Mies in his iconic 860-880 Lake Shore Drive Apartments (1951) in Chicago.

One of the most notable modern buildings outside Atlanta is New Yorker Morris Ketchum’s Kraft Bag Plant (later the SEAPAC Paper Converting Division) in St. Marys (1960), which lifts, above an open double-flight staircase, an abstract Miesian rectangular lobby that appears as a weightless, geometric volume hovering over a pool of reflecting water.

By the 1960s, however, architectural taste was already turning from the volumetric abstractions of the International style and Mies to the New Formalism and New Brutalism of a younger generation of designers. A self-consciously urban scale, a dominant formalism of shaped masses, and a new materiality marked the multiuse Atlanta complexes of Jova/Daniel/Busby at Colony Square (1969-75) and the pioneering work of John Portman at Peachtree Center (1961-present). When Portman’s Merchandise Mart of 1961 first appeared on Peachtree Street, it was less a gesture closing this early period of “emerging modernism” as it was the beginning of more than three decades of Portman’s development of Atlanta’s great agora; Peachtree Center became a market/convention complex that set a model for multipurpose developments worldwide.