Georgia folklife includes a wide range of community-shared, informally learned traditions, from the African American folktales popularized in the Uncle Remus books of Joel Chandler Harris to the mountain lore presented in the Foxfire publications and the celebrations and foods of recent immigrants. The ethnic, occupational, and locale-based diversity of Georgia folklife can be compared to a multipatterned patchwork quilt, with fishing and Geechee traditions on the coast, swamp lore in the Okefenokee, a rich pottery and blues heritage in the Piedmont, and ballad singing, fiddling, and banjo-picking in the mountains.

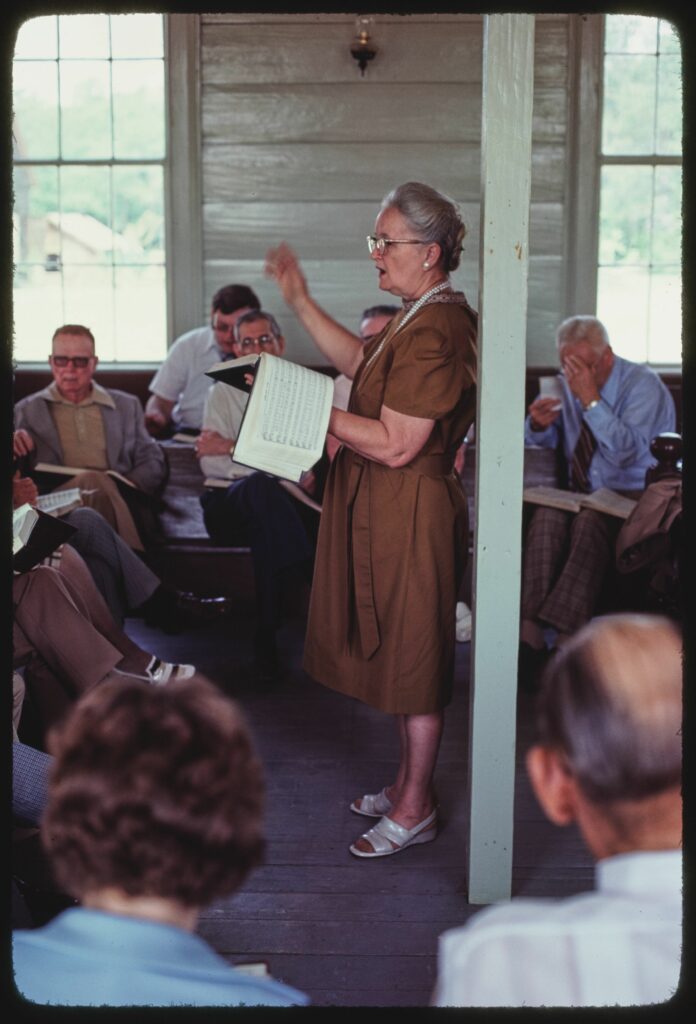

Although Georgia folklife belongs to a larger regional heritage, certain traditions have been emphasized in, or shaped by historical forces peculiar to, the state. These include Georgia’s role in commercializing southern folk music, the importance of folk pottery, and the creation of the Sacred Harp shape-note singing tradition. Early study of Georgia folklife was spotty, but since the 1970s public awareness has been heightened by a growing number of publications, festivals, and exhibits.

The historical folk culture of Georgia’s frontier era was shaped by five foundation groups: Native American, British, African, Irish, and German. Blending of traditions from these groups mainly occurred farther east, in the Carolinas and Virginia. The resulting frontier folklife—which carried the value system, provided the survival skills, and supported the quality of life for early Georgians—included community “workings” such as corn shuckings, the school ritual of “turning out” the teacher to gain a holiday, the sport of “gander pulling,” and the Christmas custom of “riding fantastic” or “sernatin’.” As older, agrarian-based traditions succumb to modernization, recently introduced urban and immigrant traditions represent the Georgia folklife of the future.

What Is Folklife?

The term folklife was coined by folklorists in the 1960s to reflect the addition of material culture (art and craft, architecture, food) to the oral, musical, and customary traditions previously studied as folklore, and to suggest the integration of all these expressive forms into people’s lives; in this article folklore and folklife are used interchangeably. A community-shared resource of accumulated knowledge, folklore is learned informally, preserved in memory and practice, and passed on through speech and body action to others in the group. Acquiring games from other children on the playground and watching older family members cook in the kitchen are familiar examples of this folk-learning process.

Given the nature of face-to-face communication, and because the human links in this chain of transmission adapt their inherited traditions to suit individual needs and the times in which they live, folklife is not static but fluid, remaining constant yet constantly changing. Before mail-order catalogs, public education, automobiles, radio, television, and computers connected Georgians to the outside world, they depended on folk traditions for their values, survival skills, and quality of life. Now more a matter of choice than necessity, folklore serves to maintain group identity and continuity with the past.

What Is Special about Georgia Folklife?

Located in the center of the lower Southeast, Georgia is surrounded by the five other states of this subregion. Since folklore is culture-based and seldom respects artificial political boundaries, we would expect Georgia to share many traditions with its neighbors; it should therefore come as no surprise that folklife on the Alabama side of the lower Chattahoochee River is no different from that of the Georgia side, for example. At the same time, Georgia’s particular geographic situation and economic, political, and settlement history have influenced its folk culture.

The short answer to the question, “What is special about Georgia folklife?” is that while much Georgia folklife does belong to a larger regional heritage, it is also possible to identify elements that, if not uniquely Georgian, have at least been emphasized here or shaped by historical forces peculiar to the state. Georgia’s contribution to commercialized southern folk music—both Black (blues) and white (string bands)—that in turn fed the American popular music idioms of rock and country is one example of the latter case; another is the big role folk pottery has played in the state’s visual arts. Further, the Sacred Harp shape-note singing tradition that is becoming more popular around the nation is a Georgia creation.

Georgia arguably is closest to Alabama, of all its neighbors, in the frontier spirit of its folk culture. The last of America’s thirteen colonies, Georgia saw significant settlement directly from the Old World only in its first three decades, and then just along the coast and Lower Savannah River corridor. The bulk of its formative population came, instead, in the late 1700s and early 1800s as a massive backcountry migration from the Carolinas (where Georgia was thought of as “the West”). Many of these new Georgians thus were seasoned southerners who brought with them a folk culture rooted in the Old World but already tempered by conditions in the Southeast.

In the final analysis, though, Georgia folklife can best be described as a multipatterned patchwork quilt rather than a bolt of cloth woven in one piece. From the Atlantic seaboard to the Appalachians, folklorists have found a broad range of traditions arising from locale, ethnicity, and occupation. Such diversity can even be present in a single place. In metropolitan Atlanta, for example, an intense Black gospel music heritage, transplanted traditions of recent immigrants, and urban lore of office “paper pushers” coexist. From the fishing and Geechee ways of the coast to the swamp lore of the Okefenokee, the cowboy culture of the wiregrass, the pottery and blues heritage of the Piedmont, and the ballad singing, fiddling, and banjo picking of the mountains, the folk stream of the state’s culture distills a sense of place and adds a rich and meaningful texture to the lives of its residents.

Early Study

Although Georgia’s folk-cultural heritage compares quite favorably with that of adjoining states, one would never know it from the early published record. When public interest in American folk music was at its height in the 1960s, for example, there was no comprehensive folk song collection for Georgia comparable to those available for other southeastern states. (There still isn’t. Art and Margo Rosenbaum’s Folk Visions and Voices, published in 1983, covers only north Georgia.)

A partial explanation for this paucity of earlier research for the state may lie in the fact that American folklore collecting often has been based in educational institutions, and folklore was not an established academic subject in Georgia until 1966, when Georgia State University’s folklore curriculum and Rabun County’s high school–based Foxfire program both began. By comparison, in 1912 Duke University professor Frank C. Brown began assembling his monumental collection of North Carolina folklore (mainly folk songs, tales, and superstitions), which was published in seven volumes between 1952 and 1961.

Brown worked in collaboration with an active state folklore society, another research asset lacking in Georgia. (A nominal Georgia Folklore Society put on an annual folk festival in the 1970s and 1980s.) Finally, Georgia simply was not fated to have a pioneering scholar like Brown in the early days of southern folklore study. Even a transient like English folklorist Cecil Sharp, who collected Appalachian folk songs between 1916 and 1918, never made it into north Georgia, although later fieldwork like that of the Rosenbaums would yield a wealth of material there. Beginning in 1926, some Georgia material was recorded for the Archive of American Folk Song (later the Archive of Folk Culture) at the Library of Congress, but little has been issued publicly.

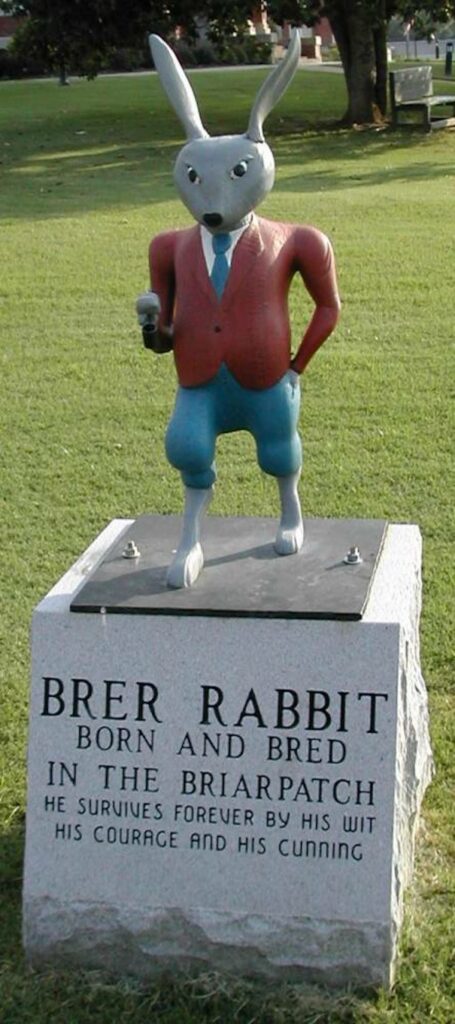

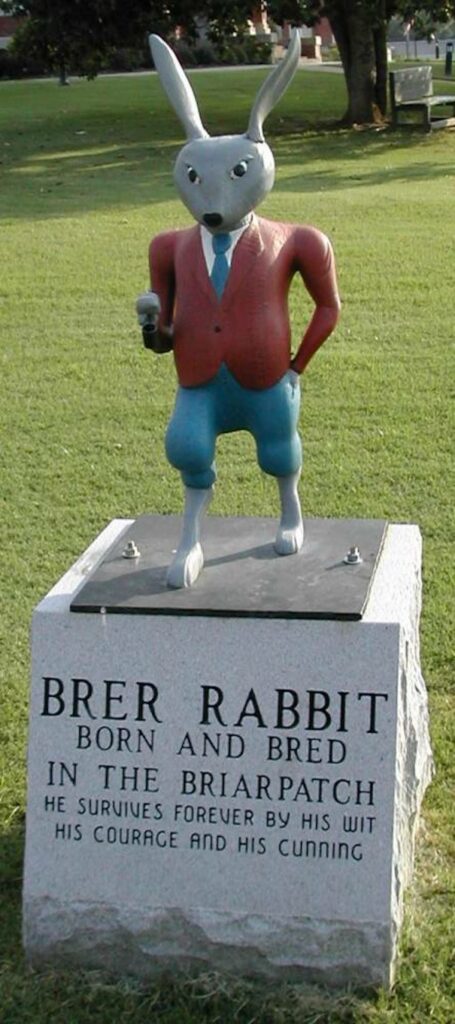

Georgia did, of course, have a pioneering folklorist of sorts in the person of Joel Chandler Harris, whose Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings (1880) and Nights with Uncle Remus (1883) brought African American folklore into the public spotlight. Harris had heard many of the animal tales (later shown to have a strong African background, as he suspected) featured in those two compilations from enslaved people in east-central Georgia’s Putnam County. But in his dialect retelling of them for print years later, with a fictitious setting and characters, he was displaying the skills of a literary artist more than those of a scholar.

Image from Mdxi

Harris’s success encouraged another white Georgian, Charles C. Jones Jr., to try his hand with similar material in Negro Myths from the Georgia Coast (1888), represented in the coastal dialect known as Gullah. The most significant Georgia folklore publications of the earlier twentieth century also document Black coastal traditions. Drums and Shadows (1940), based on interviews conducted by the Savannah Unit of the Georgia Writers’ Project (a branch of U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s depression-era Work Projects Administration), features African survivals, especially in folk belief. Slave Songs of the Georgia Sea Islands (1942), by amateur folklorist Lydia Parrish (who organized a performing group that became the Georgia Sea Island Singers), features a type of danced spiritual called the ring shout.

The emphasis on African Americans in early Georgia folklore studies makes the rural-life reminiscence—a type of nonfiction local-color literature —an important alternative resource for traditions of white Georgians. Two valuable memoirs of this type are J. L. Herring’s Saturday Night Sketches (1918), an account of late-nineteenth-century folklife in southwest Georgia’s wiregrass section, and Floyd C. Watkins and Charles Hubert Watkins’s Yesterday in the Hills (1963), a portrait of farm life in Cherokee County at the turn of the twentieth century.

By the 1970s the greater presence of folklorists in the state was beginning to yield more representative publications as well as notable folk festivals and exhibits of traditional arts. Another index of Georgia folklore’s higher profile is the awarding of eight National Heritage Fellowships (America’s equivalent of Japan’s Living National Treasures honor) to Georgians since the National Endowment for the Arts began this program in 1982. The recipients include Georgia Sea Island Singers leader Bessie Jones of St. Simons Island, Sacred Harp song leader Hugh McGraw of Bremen, and folk potter Lanier Meaders of Cleveland.

Origins

To a large extent the early folklife characteristics of the state arose within the agrarian society of Virginia and the Carolinas and was carried into Georgia by westward migration. Unlike adjacent states with substantial pioneer populations from Continental Europe (Spaniards in Florida, French Huguenots and Germans in the Carolinas), Georgia’s settlers were mainly of British Isles and African stock. Like the Lowcountry soup whose distinctly southern flavor results from a blend of African, European, and Native American ingredients, much of Georgia’s folk culture is a creolized gumbo of traditions from five influential foundation groups.

Native American

Again, Georgia folklife is conspicuous for what it lacks, in this case a continuous Native American presence. The last group of Indians remaining in the state—the Cherokees of northwest Georgia—was forcibly removed in 1838 on the Trail of Tears. In contrast, North Carolina’s Cherokees, South Carolina’s Catawbas, Alabama’s Poarch Creeks, and Florida’s Seminoles are still enriching the folk arts of their states. That does not mean, however, that Native Americans left no imprint on Georgia, for they were in contact with settlers for a century before their departure, and Indian traditions were incorporated into the frontier folklife brought from farther east.

Perhaps the most visible stamp left by Native Americans is in the form of place names, often those for features of the landscape. These include original words (or variations thereof) from the languages of historic-era Cherokees, Creeks, and such smaller groups as Chattahoochee and Okefenokee, as well as English translations, such as Ball Ground and Ball Play Creek (both locations associated with the Cherokee game related to lacrosse). This heritage is explored in John H. Goff’s Placenames of Georgia (1975). The contribution of such native food and medicinal plants as corn, beans, squash, pokeweed, and tobacco, is also significant. And it has been suggested that the frontier camp-meeting revival layout, with its brush-arbor tabernacle, was modeled on the Southeastern Indian Green Corn ceremonial square ground.

The folk culture of Indians who once occupied Georgia can now be experienced only in Oklahoma and North Carolina. In small numbers Native Americans with Georgia roots have returned to the state in recent years, but their older traditions were so disrupted that they have had to revive them or adopt Indian ways from other parts of the country.

British

The most important Old World source area for early Georgia folklife was Great Britain. Southern England supplied a great number of colonists to the Virginia, Carolina, and Georgia tidewater, while northern England, Wales, and lowland Scotland influenced the backcountry less directly via the mid-Atlantic. In addition, Highland Scots settled on the coasts of Georgia (at Darien) and North Carolina (Cape Fear). These British groups contributed a wide range of traditions in oral literature, custom, and material culture to the core of Georgia folklife.

Here are just a few concrete examples. In southern vernacular architecture, the square one-room cabin harks back to lower-class cottages of medieval England, while the hall-and-parlor house is a middle-class Renaissance form. In folk pottery, predecessors of the southern cane-syrup jug and lug-handled food-storage jar can be seen in northern England. The oldest folk ballads sung in Georgia, such as “Barbara Allen” and “Lord Thomas and Fair Eleanor,” are British imports. The Georgia folk game of “town ball” (known also in the North, where it was formalized into baseball) had its origins as “bittle-battle” in England (evolving there into cricket). And the southern superstition that a household will be blessed with good luck if a man is the first to enter on New Year’s appears to be based on the “first foot” custom of Scotland and northern England.

African

The only people to come to the United States against their will, enslaved Africans nevertheless made major contributions to southern folk culture. Representing a variety of language and tribal groups, they were brought mainly from a crescent of west-central Africa marked by Senegal at its north and Angola at its south. Southern speech incorporates such African words as goober (the folk name for peanut, from the Kimbundu word nguba), gumbo (from the Tshiluba word for okra), chigger (the Wolof word for small flea), and juke (also Wolof, meaning disorderly). West African retentions are especially strong on the coast, as linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner pointed out in Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect (1949).

The banjo, later adopted for upland white folk music, began as a slave instrument based on West African prototypes. From ring shouts to modern gospel, such Black Georgia singing traits as antiphony (call-and-response) with natural harmony and hand clapping accompaniment are rooted in African choral style. The log mortar and pestles for hulling rice, the coiled-grass basket, and the circular cast-net for fishing are coastal folk artifacts with links to Africa. More widespread was the magical practice known as hoodoo or conjure. And the African background of many Brer Rabbit folktales already has been mentioned.

Irish

Lowland Scots and northern English settled in Ireland’s northern province when James I established the Ulster Plantation in 1609. A bit more than a century later, these Ulster Protestants—known to Americans as the Scots-Irish—began flooding into Pennsylvania. Moving south as a major part of the backcountry population, they transplanted traditions from northern Ireland to Appalachia. Other Irish immigrants—this time mostly Catholic—arrived in the nineteenth century; their numbers were greatest in the North, but their presence in Georgia is reflected in the St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in Savannah and Atlanta.

The Scots-Irish adapted their Ulster distilling technology to the New World grain, corn, to produce the illicit whiskey known as moonshine. They also brought an ancient two-room cabin type, with front and rear opposing doors in the larger, fireplace room, and grafted to it the log construction of the backcountry. These rectangular log cabins often were furnished with a lidded meal bin having two compartments, one for cornmeal (oatmeal back in Ireland) and the other for wheat flour. But on Saturday nights such furniture was cleared to make room for dancing to the accompaniment of the fiddle with its characteristic drone sound. The solo buck dance may derive from Irish step dancing, and many of the old tunes, such as “Soldier’s Joy,” “Leather Britches,” and “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” can be traced to Ireland and Scotland. The mountain singer’s “high, lonesome” sound is rooted in Ireland’s sean nós (old style), and some of the mountain “Jack tales” seem to have been brought from Ulster.

Germanic

The southern upland culture complex in which north Georgia participates includes Germanic and Nordic traits first brought to the mid-Atlantic. Horizontal log construction with corner-notched joints, the prevalent southern backcountry building technique, first came with Finno-Swedes to the Delaware Valley and was reinforced by Moravians and Swiss. The stringed instrument known as the Appalachian dulcimer (rare in Georgia until a 1960s revival) most likely developed from the Pennsylvania-German Scheitholt. A final Germanic adoption is the upland food tradition of salt-pickling cabbage to make sauerkraut.

Frontier Folklife

The living traditions emphasized in other folklife entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia are studied through fieldwork, in which people who practice folklore are observed and recorded at their homes. However, many important Georgia folk traditions tied to the frontier lifestyle have become extinct in the course of modernization. Historical documents therefore are an essential resource for their reconstruction.

The isolation created by rural Georgia’s dispersed settlement made community “workings” (called “bees” in the North) especially welcome. Neighbors reciprocally helped each other with agricultural chores that could overwhelm a single family. Especially popular were log rollings, in which teams of men would carry away felled trees to clear new ground for planting, and corn shuckings, in which husks were stripped from a large pile of harvested corn. African Americans elaborated the latter event into an art form that included competition between two teams led by “generals,” call-and-response singing of shucking songs, and wrestling matches. Such workings, then, had both a practical and social function; often they included a feast prepared by the women (who also participated in a quilting at the host house) and concluded with a square dance.

Formal education would seem to be inhospitable to folklore, but traditions that express the unofficial attitudes of students and teachers do indeed exist. This is no less true for early Georgia, where the ritual of the “turn-out” held sway. Before state-funded public education, a teacher was paid directly by parents, who would withhold some pay if he freely gave his students a holiday. So, with an adult often serving as witness and mediator, the pupils would barricade themselves inside the schoolhouse and prevent the “master” from entering until he was forced to grant them the holiday. This curious custom dates to the 1500s and was called “barring out” back in northern England, lowland Scotland, and Ulster. It is first described for the southern backcountry in Augustus Baldwin Longstreet’s Georgia Scenes (1835), set in 1790s Augusta.

Longstreet’s book, while fiction, offers a fairly reliable account (judging by corroborative evidence) of early Georgia folklife. Another of his sketches provides the first report of a frontier sport later documented throughout the South, the “gander pulling.” Vaguely inspired by medieval jousting tournaments, it involved hanging a live male goose by the feet over a racetrack, with the contestants trying to grab its greased neck and pull off its head while galloping their horses below. The victor’s prize was the collected entrance fees.

Early Christmas customs offer a dramatic contrast to today’s commercialized holiday. Along with shooting off firecrackers and guns and competing to first shout “Christmas gift” on Christmas morning, Georgians celebrated in a manner more reminiscent of Halloween or Cajun Mardi Gras. Parties of disguised teenagers, known as fantastics in the daytime and sernaters at night, walked or rode horses from house to house begging for treats and entertaining neighbors. Homemade masks called “dough-faces,” cross-dressing, and pranks were variables; towns like Savannah and Decatur took the more structured approach of costumed parades. Derived from the old British custom of “mumming” or “guising,” “riding fantastic/sernatin'” died out with the coming of the automobile and survives only in the memories of some older Georgians.

Georgia Folklife Today

The changes wrought by modernization, accelerating since the early twentieth century, clearly have had an impact on the folklife once central to Georgia’s agrarian society. Some declining older traditions, such as folk pottery, blues, and Sacred Harp singing, have been given a new lease on life by a new—largely urban—audience. Others have been displaced by the nonregional folklore of a mobile national culture. For example, urban legends triggered by current events and modern anxieties may be localized with Georgia settings but in fact are more widespread. Overall, Georgia folklife is not vanishing but changing in character.

Another big change in Georgia folklife results from the state’s shifting demography, as large immigrant populations from Asia, Latin America, the West Indies, and most recently Eastern Europe bring their traditions and transplant them in Georgia soil. As these new ingredients are added, the Georgia folklife gumbo continues to cook and change its flavor.