Georgians have made moonshine since the late eighteenth century. During the colonial and antebellum periods, its production played an important role in the state’s agrarian economy. The distillation of apples, corn, or peaches into whiskey, brandy, or other alcoholic forms became a cottage industry that allowed small farmers to obtain cash. Though most often associated with the mountainous area of north Georgia, moonshining was practiced by farmers throughout the state.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The Scots-Irish, immigrants from the province of Ulster in Northern Ireland, brought the practice of distilling alcohol to the backcountry of Georgia and other American colonies during the eighteenth century. Moonshine production is an involved process but not so difficult that men of relatively few resources could not master it. Two steps—fermentation and distillation—are involved in making whiskey or brandy, which the historian Joseph Dabney explains in his book Mountain Spirits:

During the fermentation process, the starches in the grain (or the fruit) are broken down through saccharification into sugars and then the sugars into alcohol. This process is speeded up greatly by the infusion of sugar, yeast, and/or malt. . . . In whiskey making, the basic fermenting mixture of grain, water, and other ingredients is called”mash.”. . . To go from the fermented mash to alcohol itself requires the additional step of distillation. In this process the essence, or spirit, of the fermented liquid is separated from the water by being heated to the appropriate temperature. . . . The resulting vapor lifts the alcohol essence out of the water, and the vapor is then reconverted to liquid by cooling.

This liquid is collected in jars or other containers. The apparatus itself is referred to as a still.

Moonshine was a practical enterprise. Farmers discovered that they could earn extra money by manufacturing excess yields of their crops into corn whiskey or apple and peach brandy, and selling it. Because of the region’s rugged terrain and poor roads, north Georgia farmers also found it easier and more profitable to distill some of their crops before carrying them to market. Antebellum Georgians viewed distillers as well-respected members of the community and denounced the federal government’s attempt to impose a tax on liquor manufacturing in the 1790s.

Moonshine “Wars”

During the Civil War (1861-65) the U.S. Congress attempted to balance the national budget by creating the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to collect taxes on liquor, tobacco, and other “luxuries.” When they returned to the Union after the war, Georgians found themselves subject to this federal liquor tax. Many moonshine producers, mostly small farmers, refused either to discontinue their moonshine operations or to pay the tax on it. The production of moonshine was not in and of itself illegal, but attempts by producers to avoid paying the federal tax were. Such people became known as “moonshiners” because they operated their illegal stills at night.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

This sparked a much-publicized war in north Georgia between moonshiners and revenuers, the federal agents who sought to enforce the liquor law. Moonshiners attacked revenuers and intimidated local residents who might otherwise be tempted to help revenuers identify lawbreakers. In the early 1870s the Ku Klux Klan joined forces with them to combat the IRS. The historian Wilbur Miller estimated that in 1876 four-fifths of all federal law-enforcement efforts and court cases in the Georgia mountains involved illegal liquor issues, more than for the highland areas of any other state.

The brutal tactics used by moonshiners who resisted revenuers led to a shift in the public’s perception of distillers. Many Georgians elsewhere in the state began to support the federal government. During the 1880s their sentiments fueled the temperance movement, led primarily by evangelicals, women, and journalists, which encouraged Georgians to refrain from drinking and to accept federal liquor taxation as a means of decreasing alcohol consumption. These Prohibitionists increasingly portrayed moonshining mountaineers as violent criminals on the fringes of society. By 1900 many north Georgia communities had ceased supporting the moonshining activity in their midst.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

During the twentieth century the moonshiner degenerated from a skilled craftsman to a greedy gangster. The prohibition era began with the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1919 and its implementation in 1920 through the Volstead Act, in which Congress declared all alcohol manufacturing and consumption illegal. (Georgia had already passed a similar law in 19 07.) Prohibition increased the demand for moonshine. Gangsters soon cornered the market, creating elaborate moonshining networks and forcing farmers to run stills for them.

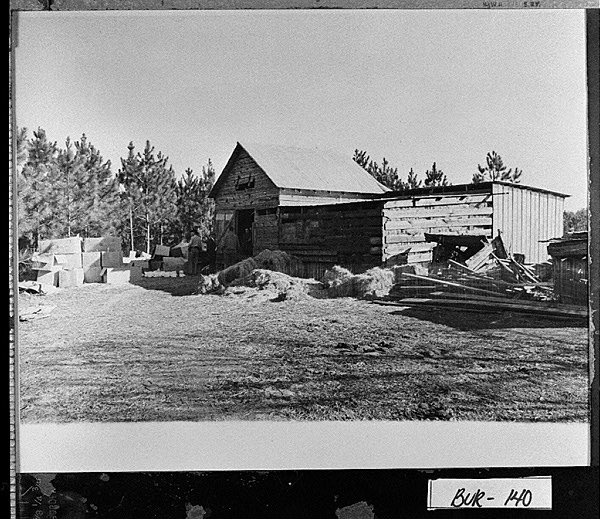

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

In the mountain county of Dawson, moonshiners ran millions of gallons of whiskey into Atlanta. Other mountain counties, like Gilmer, Lumpkin, and Pickens, became major producers of moonshine in the 1930s and 1940s. Moonshiners played a dangerous game of cat and mouse with revenuers. In Dawson, Union, and other counties, so-called trippers designed high-performance automobiles, called “tanker cars” (most often 1940 Fords), to evade revenuers. Such car chases often ended in the death of the moonshiner or the revenuer. Out of these powerful cars and high-speed chases grew the sport known today as stock car racing (NASCAR).

Portrayals of Moonshiners

In the process of such blockade running, moonshiners had become reckless outlaws who were concerned only with making money rather than manufacturing quality whiskey. In a full chapter on the subject in his memoir, The Mountains within Me, former Georgia governor Zell Miller explains the changes he observed in the business in and around his native county of Towns. Fewer local families engaged in liquor trafficking, and those who did had become “a breed apart from their ancestors to whom making whiskey was a personal custom-sanctioned activity that was incidental to their total livelihood and not a calculated, law-breaking enterprise.”

Moonshiners also figure prominently in the autobiographical literature produced by other Georgians. Rick Bragg devotes his second book, Ava’s Man, to his maternal grandfather, Charlie Bundrum, whose illicit whiskey operation in and around Floyd County in the 1930s and 1940s was one of several enterprises by which he supported his large, poverty-stricken family. In an essay entitled “Mountain Spirits,” published in the Sewanee Review, James Kilgo writes of an uncomfortable encounter he had while on a fishing trip in Rabun County: two locals offered him their homemade brew, bemoaning the fact that people had lost pride in making whiskey and that so much of the “radiator likker they’re selling now will kill you.”

Several Georgians have written about family members’ run-ins with the law. In The Last Radio Baby, an account of growing up Black in Morgan County, Raymond Andrews tells of an uncle who spent a year on the chain gang after being caught operating a liquor still in 1933. In Ecology of a Cracker Childhood Janisse Ray tells the story of her grandmother, who sold bootleg whiskey in half-pint jars from her kitchen in south Georgia until she was caught and prosecuted by an IRS agent in 1945. A judge in Brunswick released her on probation, and she never sold another drop. Harry Crews, in A Childhood: The Biography of a Place, writes of an uncle who was killed at his still in Bacon County in south Georgia by a federal agent.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Since the 1960s moonshining activity has slowed considerably, and much of it has migrated from the mountains to metropolitan areas, where producers have found it easier to evade the federal liquor tax. They place their illicit stills in homes and barns, which revenuers (who now work under the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives) must have a search warrant to enter.

Today, any lost tax revenue from the sale of illegal liquor is of less concern to officials than the health threat posed by moonshine. Because moonshine contains impurities and toxins, especially lead, moonshine consumption can be deadly. Poor people have suffered most, since moonshine is extremely inexpensive, and illegal distributors may target poor neighborhoods in which to sell their products.